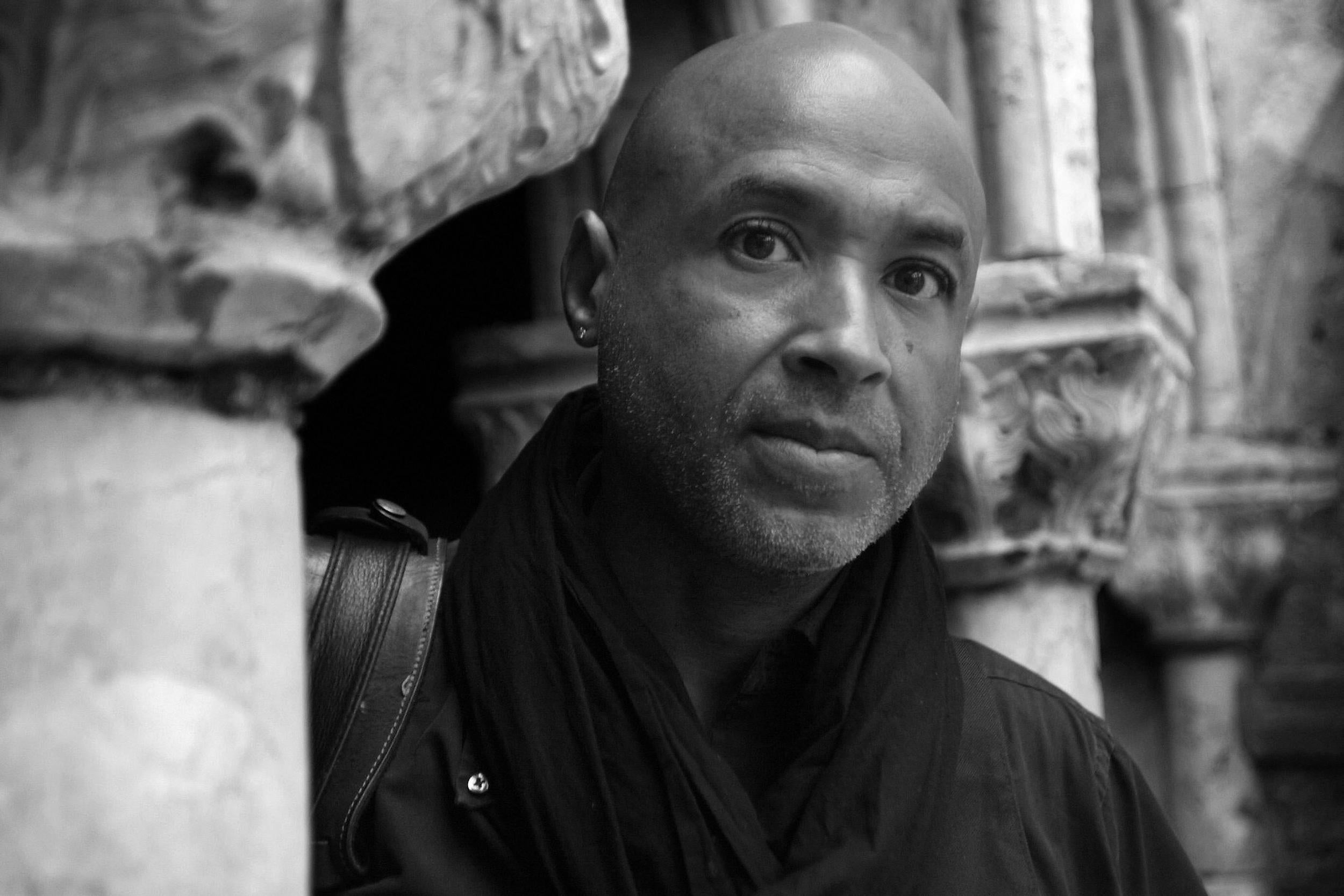

Stanley Greene, obituary: Celebrated photojournalist who shone a light on war's brutality

The former Black Panther was an internationally celebrated truth-teller who refused to remain objective in the face of genocide and war

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Stanley Greene was a former Black Panther who became a celebrated international photojournalist, portraying war, poverty and disaster in Chechnya, Afghanistan, Iraq and the US Gulf Coast after Hurricane Katrina.

In his youth, Greene dabbled in radical politics and spent time in a psychiatric hospital before becoming an assistant to the acclaimed photojournalist W Eugene Smith in the early 1970s. He chronicled the punk rock scene in San Francisco in the 1970s and early 1980s before moving to Paris, where he worked as a fashion photographer.

“I was a dilettante,” he said in 2004, “sitting in cafes, taking pictures of girls and doing heroin.”

His career in photojournalism began as “an accident” when he was 40. He was on assignment in East Berlin in 1989 when the moment the Berlin Wall was breached. His photograph of a young woman in a tutu on top of the wall was reprinted all over the world. She was above the scrawled phrase “Kisses to All,” waving a bottle of champagne as guards descended on her. Amid the collapse of the Communist bloc, Greene had discovered his vocation.

“I honestly believe photography is 75 per cent chance and 25 per cent skill,” he said. “In accidents, we really discover the magic of photography.”

Wherever he went, Greene cut a striking figure in his black leather jacket and sunglasses, adorned with scarves, rings, bracelets and a bandoleer of film canisters across his chest. “He was very charismatic,” recalled his friend and colleague Kadir van Lohuizen. “People would melt for him because there was integrity in his eyes.”

Greene took his cameras to countries including Croatia, Kashmir, Afghanistan and Lebanon. He covered genocide in Rwanda and strife in Azerbaijan, Iraq and Syria. In Mali in the early 1990s, he saw children dying of starvation, flies crawling across their faces.

“I photographed them as I would a fashion model,” Greene later wrote. He was unhappy with the results, “but they taught me a lesson. You have to take photographs from the heart and not from the head.”

Remembering the example of Smith, his mentor, Greene sought powerful, sometimes dangerous assignments that could document the human struggle. In 1993, he was the only western journalist inside the Russian parliament building when it came under siege during a violent coup attempt that left almost 200 dead.

“The fact that I thought I was going to die gave me courage,” Greene recalled in 2010. “Courage is control of fear. I think that this incident is the one that steeled me.”

He travelled more than 20 times to Chechnya, where he chronicled the devastation wrought by Russian troops as they battled separatists in the former Soviet republic. “There are stories that get to you so deeply that you have to get them out - and this was mine,” Greene said.

His 2003 book Open Wound: Chechnya 1994 to 2003 was “a testament to the fact that photography's moral force is alive and well,” the Toronto Star foreign correspondent Olivia Ward wrote in 2004.

Greene was one of the few western journalists in Fallujah, Iraq, in 2004, when four US contractors were killed. Their bodies were burned and then hung from a bridge. “It was the most horrendous thing to see,” he said. “The people were standing around – they were like at a barbecue.”

Shortly after Hurricane Katrina flooded New Orleans and the Gulf Coast in 2005, Greene was there to photograph the physical and psychic damage. He returned for the next five years, showing how the lives of thousands of people had been forever changed.

As a photographer, Greene was a strict classicist of the old school: He preferred shooting film on Leica and Nikon cameras and detested the digital manipulation of images. But as a journalist who walked into war zones with only his cameras, he didn't believe there was such a thing as impartiality.

“I have been accused of having lost my objectivity,” he said. “But when you sit on a fence and watch genocide without doing anything about it, you are as guilty as those who are committing it.”

Stanley Norman Greene Jr was born in 1949 in Brooklyn. Both his parents were actors and social activists. His father, who was blacklisted for his political beliefs in the 1950s, had roles in the films For Love of Ivy and The Wiz. The younger Greene “was that kid my parents told me to stay away from,” he recalled in 2008. He took part in antiwar demonstrations and joined the Black Panthers, later sheepishly admitting, “I was attracted to the Panthers by the berets and leather jackets.”

Because of drugs and behavioural problems, he spent two years in a psychiatric hospital in his teens. In the early 1970s, he became an assistant to Smith, whose photographic essays in Life magazine and other publications are considered landmarks of the form.

Greene later moved to San Francisco to study, eventually earning a master's degree from the San Francisco Art Institute in 1980. While there, he photographed the city's thriving music scene and its equally thriving drug underworld.

He briefly worked at Newsday – “I was constantly doing delicatessen openings” – before moving to Paris in 1986. In 2007, Greene, van Lohuizen and other photographers formed the Paris-based NOOR photo agency.

Greene, who died of liver cancer, received five World Press Photo awards, among other honours, and in 2010 published a photographic memoir, Black Passport. He often spoke at international photography conferences. He was married at least twice, had numerous girlfriends over the years but no children.

Greene's photography appeared in many of the world's best-known magazines, but he often had to finance his travels from his own shallow pocket. “I live from hand to mouth,” he said in 2010. “Let's be real here. I don't own an apartment. I don't own a house. I don't own a car. I don't have any stocks and bonds. All I own are my cameras.”

In recent years, he had documented the environmental and human cost of the digital age, travelling to Nigeria, India, China and Pakistan, where people salvaged discarded electronic devices from waste dumps. He said he was not interested in quick-hit photography but preferred deep-immersion assignments in which he could explore complex visual tales.

“I think at the end of the day we have to be storytellers,” Greene told Italian Vogue in 2013. “Yeah, I think that you have to be obsessed.”

Stanley Greene, photojournalist, born 14 February 1949; died 19 May 2017

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments