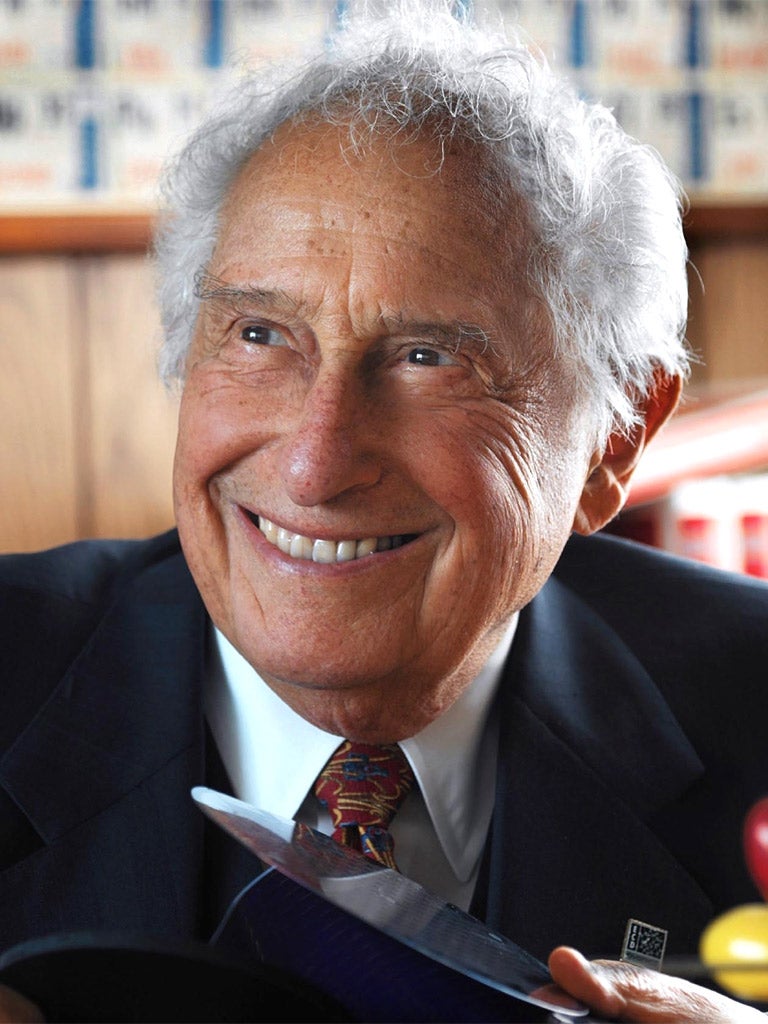

Stanford Ovshinsky: Pioneering inventor

Stanford Ovshinsky was a self-taught inventor whose innovations have been incorporated into many hi-tech developments, from flat-screen televisions to laptop computers, He devised the term "ovonics", combining his own name and "electronics," to describe the technology behind the development of what he called "non-depletable, non-polluting energy sources." His aim was to reduce the world's dependence on fossil fuels with solar power and hydrogen. In 1999, Time included Ovshinsky among its "Heroes for the Planet."

Ovshinsky, who died on 17 October at the age of 89, began his career as a machinist but developed a reputation as an original thinker who designed solar panels, hydrogen fuel cells, semiconductors and rewritable compact disks long before they reached the mainstream market. He had more than 200 patents, but the company he founded in 1960, Energy Conversion Devices, lost money for decades. For years, he was seen as a quixotic genius who couldn't translate his ideas from the laboratory to the marketplace.

"Ovshinsky has created things that aren't manufacturable," a Wall Street analyst told Forbes magazine in 1980. "After 20 years, one gets impatient. Where is the product, and where is the profit?" Yet his breakthroughs, coupled with his enthusiasm, kept industrial giants knocking on his door, betting millions that his inventions would transform everything from car design to home entertainment.

He was born in 1922 in Akron, Ohio, receiving his first patent at 24, for an automated lathe design. He moved to Detroit in 1952 to work as research director for an car company before establishing a company with his second wife, Iris Dibner, a biochemist.

In the 1950s he proposed hydrogen-based fuel cells as an alternative to the internal combustion engine. He designed the first nickel-hydride batteries, which are now used in hybrid cars. Much of his work was devoted to photovoltaic solar panels.

He also worked extensively on amorphous semiconductor technology, in which the materials lacked a crystalline atomic structure. He developed a process for applying a microscopically thin layer of amorphous material on sheets of plastic or stainless steel, which later spurred the development of rewritable computer disks and digital video discs, or DVDs.

Ovshinsky never attended college and was not affiliated with a major institution, so many of his ideas were not taken seriously at first. His developments gained acceptance in Japan before they did in the US. "We've tried for years to get American companies interested in our work, but we haven't had much luck until recently," Ovshinsky said in 1986. "Once the Japanese starting coming aboard, the Americans began to take a look."

Ovshinsky believed that many US energy and car companies found him a threat to their technologies and bottom lines. "Of course the oil companies are not very happy," he said. "And the automotive companies would like to postpone the day of change as long as they can. I don't relish the role of being a prophet in the wilderness. But I recognise that we're agents of change and change is difficult."

Matt Schudel

Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks