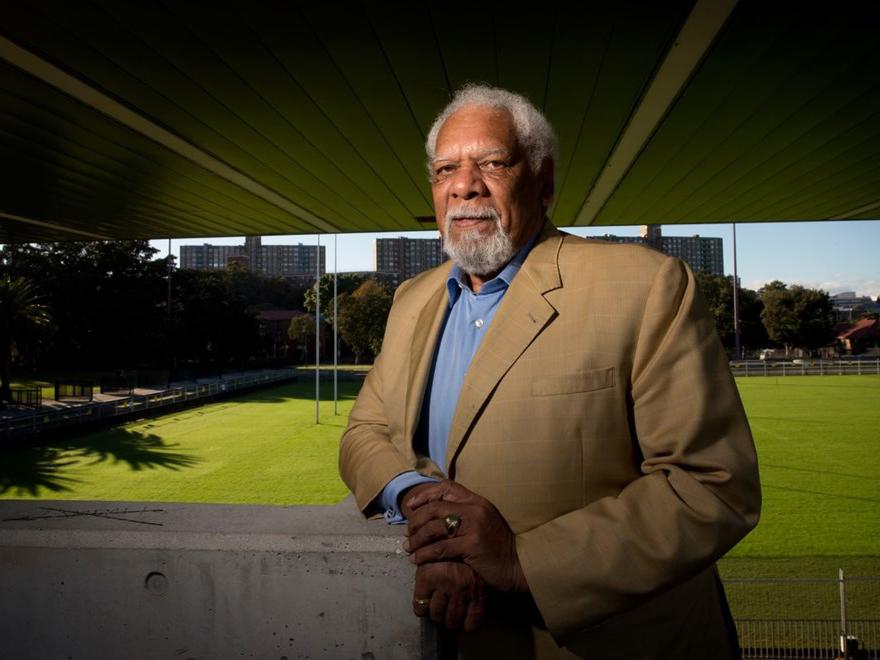

Sol Bellear: Indigenous Australian civil rights leader, rugby player and veteran of the land rights movement

A black power salute cost Sol Bellear his athletic career, but he returned to both sport and politics to fight for a people demanding recognition in their own country

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“I’m Sol Bellear, a Bundjalung man. I come from a little place called Mullumbimby.”

That’s how the Australian civil rights activist, who has died aged 64, introduced himself on the website of the New South Wales Aboriginal Land Council. The Bundjalung tribal lands of New South Wales were Bellear’s birthplace and the place he held closest to his heart but his outlook was by no means parochial.

Bellear was born in 1950 or 1951; around 300,000 of Australia’s indigenous peoples, virtually half its population of 770,000, do not have their births registered – there is now a government programme encouraging them to do so.

There were five girls and four boys in Bellear’s family, though one of his sisters would die in childhood. Bellear was a keen sportsman and in his late teens he joined local rugby league team, the South Sydney Rabbitohs.

Bellear, however, could not ignore the fact of belonging to an oppressed people. “That hard-on racism I got when I moved to Sydney I could not believe,” he later said. “It was shocking; it was really, really horrible.”

Inspired by the civil rights movement in the United States, he dared to give a black power salute after scoring a try. He was dropped as a player from the squad.

It was 1967. Australia was voting in a referendum that proposed to include Indigenous Australians in the census and change the constitution to allow the government to make laws for Aboriginal people. Those who were against including indigenous people in the census feared it would change the balance of the number of seats each state held in parliament. More Indigenous Australians meant more seats and more power for states such as New South Wales.

“Things should be so much better for Aboriginal people,” he told writer Paul Daley. “I think the country saw 1967 as the end of the fight. Before 1967, we weren’t counted in the census or anything as people. Dogs and cats and pigs and sheep were counted in Australia before Aboriginal people.”

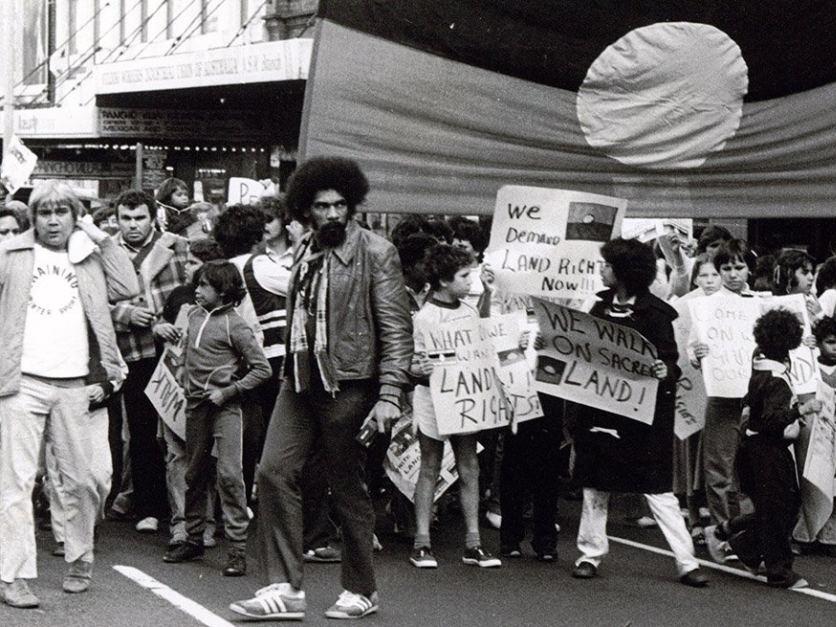

Bellear’s sacking from the Rabbitohs only served to fuel his sense of injustice. In 1970, he was part of a delegation that travelled to Atlanta to address the United Nations General Assembly. Returning to Australia, Bellear was active in the first of the “Tent Embassy” protests, in which activists set up tents opposite municipal buildings to make a stand against the government’s approach to indigenous land rights.

This was summed up by one judge in a 1971 ruling: “No doctrine of common law ever required or now requires a British government to recognise land rights under Aboriginal law which may have existed prior to the 1788 occupation.”

Bellear paid great attention to the apartheid struggle in South Africa and First Nations social justice issues in the US, all the while accruing intellectual ballast to bolster his case for the benefits of self-determination. He spent time with Maori communities and studied various systems for indigenous peoples, like the Sami parliament of Norway.

Together with his brother Bob, who had become a judge, Bellear was instrumental in founding the Aboriginal Legal Service. He also helped to found the Aboriginal Housing Company and Aboriginal Medical Service Redfern, alongside its director, his sister LaVerne Bellear. He was deputy chair of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission, and supported last year’s Uluru Convention – a gathering of indigenous leaders whose objective is summed up in the “Statement from the heart” issued in October: “We seek constitutional reforms to empower our people and take a rightful place in our own country.”

Arguably one of the most important moments in Bellear’s career as an activist came on the 10 December 1992, when he took to the stage at the Redfern Oval to introduce Prime Minister Paul Keating. Keating gave a speech that cut to the heart of the issues Bellear was fighting so hard to overcome. Keating called for recognition of the damage inflicted upon the indigenous Australians by settlers, admitting, “We took the traditional lands and smashed the traditional way of life.”

Bellear said of the moment Keating started speaking, “He was a bit nervous, you know, and you could see the anguish on the faces of non-Aboriginal people ... and then the looks on the faces of Aboriginal people as he started to talk about the murders and the oppression. And you could see Aboriginal people in the park saying to each other, ‘Fuck yeah – that’s right, that’s it – he’s nailed it.’”

It was a watershed moment. However, Bellear would lament almost a quarter of a century later, “how the fuck is it that the lot of my people has since improved so little?”

In 1999, Bellear was awarded Member of the Order of Australia for services to the Aboriginal community, and for his healthcare work in particular.

Throughout his life, Bellear remained a keen participant and supporter of Rugby League. Dropped from the Rabbitohs for his activism in the Sixties, he returned to the team as a board member later on. He had also played for the Redfern All Blacks, revealing in a radio interview that while the Redfern All Blacks were an all-Aboriginal side, they were actually named for the colour of their socks. In 2016, he was a celebrity judge at the National Indigenous Football Championships.

Like his barrister brother Bob before him, Bellear was honoured with a state funeral. On what was billed as “Sol’s last march”, more than a thousand mourners accompanied his final journey from the offices of Aboriginal Medical Services Redfern to the Redfern Oval, home of the Rabbitohs.

Fellow activist and scholar Paul Coe, speaking at the funeral, summed up his friend’s philosophy: “Solly had an outlook on life. You need more than anger to change the world.”

Aptly, his life was celebrated in the place where almost exactly 25 years earlier he had introduced Keating to the crowd and made history.

Remembering that momentous day, Bellear once said, “It all goes back to history in this country”, later lamenting: “We don’t learn the lessons of our history.”

Bellear is survived by his partner Naomi Mayers and by his children, daughter Tamara and son Joseph.

Solomon ‘Sol’ Bellear, born 1950/1951, died 29 November 2017

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments