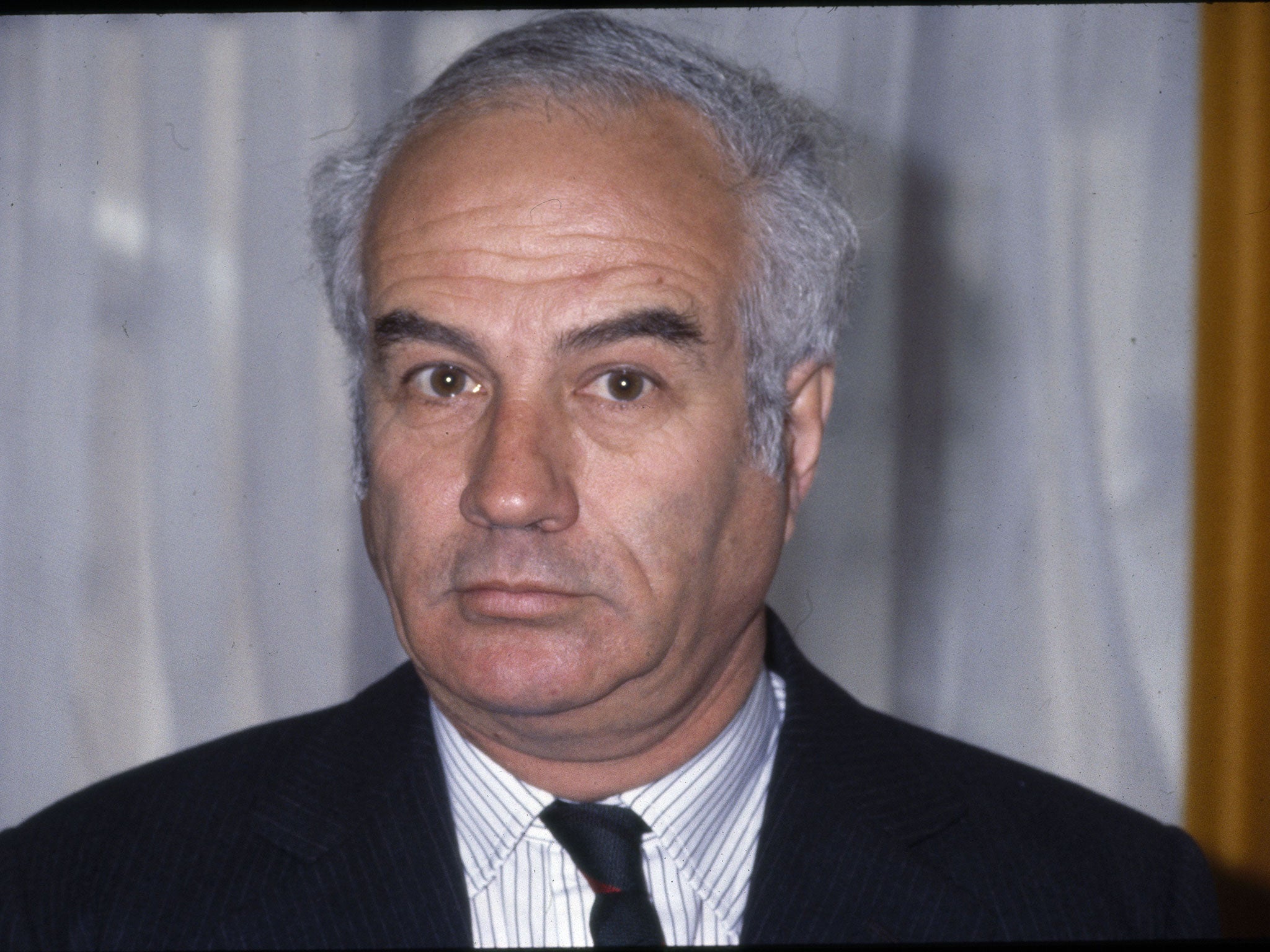

Sir Philip Goodhart: Margaret Thatcher's MP who was always ahead of his game

MP and stalwart of the 1922 Committee served as a minister in Thatcher's government

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Philip Goodhart had too much independence of mind to be easily pigeon-holed within the ranks of the Conservative party and it was almost inevitable that his tenure of office should be brief. He served a record 19 years as a secretary of the Conservative backbench 1922 Committee, and wrote its history. His study provided insight but was too discreet to be a definitive assessment of that highly influential body.

Philip Goodhart had too much independence of mind to be easily pigeon-holed within the ranks of the Conservative party and it was almost inevitable that his tenure of office should be brief. He served a record 19 years as a secretary of the Conservative backbench 1922 Committee, and wrote its history. His study provided insight but was too discreet to be a definitive assessment of that highly influential body.

His major contribution to British politics was made as an early campaigner for a referendum on British membership of the European Economic Community and he voted against entry because Heath had refused to put the issue to the British people. But his support for referendums was not confined to that issue. Later he campaigned for making use of the device on devolution, the Anglo-Irish Agreement and the Maastricht Treaty.

He quoted Balfour: “In the referendum lies our hope of getting the sort of constitutional security which every other country but our own enjoys ...”; and the case he made for its use in Referendum (1970) displays the intelligence, skill in argument and knowledge of history that earned him the respect as well as the affection of his parliamentary colleagues.

Although he was a member of the Conservative One Nation Group, his belief in capital punishment and his advocacy of controls on immigration led to a widespread belief that he was on the right of the party, a belief strengthened by his hostility to the Labour Government’s treatment of Southern Rhodesia. But later advocacy of a £900 million programme to provide employment, the foundation of the Conservative Action to Revive Employment, and opposition to the poll tax led many to think him a wet.

But he was always his own man, reasoning his way to some prescient and some unorthodox positions. For example, he argued against Trident on the grounds that it would distort spending on the Navy and suggested instead submarine-borne Cruise missiles. He also wanted to give West Falkland to the Argentinians – of course, after a referendum.

Goodhart specialised in defence and Alec Douglas Home found a place for him on the front bench in opposition in 1964. In the subsequent leadership election he backed Maudling; six months later Heath relegated him to the back benches.

In 1975, back on the 1922 Committee, he was certain that Heath must go, less certain about Margaret Thatcher as his successor. Goodhart’s knowledge and interest in Ulster – he had been encouraged to form the Ulster Conservative Group to maintain links with the Unionists after they broke with the party – led her to appoint him as a junior minister in the Northern Ireland Office in 1979.

Subsequently he went to Defence in January 1981, initially as minister for the Army, but adding the other services to his portfolio after Keith Speed’s resignation. He was to wonder in retrospect whether the cuts to the Navy, which he supported, had led to the Argentinian invasion of the Falkland Islands. He made no secret of his dislike for this ministerial set-up and may not have been too surprised to be given a knighthood and dropped from Thatcher’s team in 1981.

His differences with her grew as he opposed charges on hearing and eye tests and opposed cuts to housing benefit. He voted against her leadership in 1990 and gave his support to Michael Heseltine.

Goodhart was an inveterate campaigner. One of the few British MPs to support the American campaign in Vietnam to the end, he urged the cause of the Vietnam boat people after the Communist victory. At home he campaigned for red routes, speed cameras and road humps. For 20 years he was a council member of the Consumers’ Association and in 1971 he promoted the Unsolicited Goods and Services Act which outlawed “inertia selling”.

Often he was ahead of his time, calling for a register for sex offenders, for example, almost as soon as he was elected to Parliament. He also advocated automatic train control after the Lewisham disaster in which several of his constituents perished, non-lethal gases for use by troops, and in 1975 counter-terrorist technology linked to identity cards. However his efforts suffered from one major drawback, an inability to translate his clear thinking into speech without near fatal hesitations. On paper he was always lucid.

Although his father, Arthur Lehman Goodhart, was American, Philip Carter Goodhart was born in London and educated at the Dragon School in Oxford, where Arthur held the chair in jurisprudence. Goodhart then attended the Hotchkiss School in Lakeview, Connecticut, but returned in 1943 to join the King’s Royal Rifle Corps.

After the war he served with the 1st Parachute Battalion in Palestine. On demobilisation, he read history at Trinity College, Cambridge. In his final year he contested the safe Labour seat of Consett in the February 1950 election.

He had edited the University newspaper, Varsity, and after graduation chose not to join the family bank, Lehmann Brothers, but to accept a post as leader writer on the Daily Telegraph. In 1955 he became deputy editor of Time and Tide but soon moved to the Sunday Times. In 1956 he hitchhiked to Port Said to cover the British invasion of Egypt.

Despite his criticism of the rupture in the Anglo-American alliance, which may have cost him selection in Warwick and Leamington, he impressed the Conservative executive in Beckenham: they chose him to fight a by-election in February 1957. He held the seat at nine General Elections, standing down in 1992. Among his other publications are a valuable account of the 1975 referendum, Full-Hearted Consent, and Fifty Destroyers that Saved the World, a study of the beginnings of Anglo-American co-operation in the Second World War.

Goodhart was married to Valerie Winant, daughter of the wartime American Ambassador to Britain; she died a year before her husband. One of their seven children is David Goodhart, former editor of Prospect magazine and now director of the think tank, Demos.

Philip Carter Goodhart, politician: born London 3 November 1925; MP for Beckenham 1957–1992; Kt 1981; married 1950 Valerie Winant (died 2014; four daughters, three sons); died London 5 July 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments