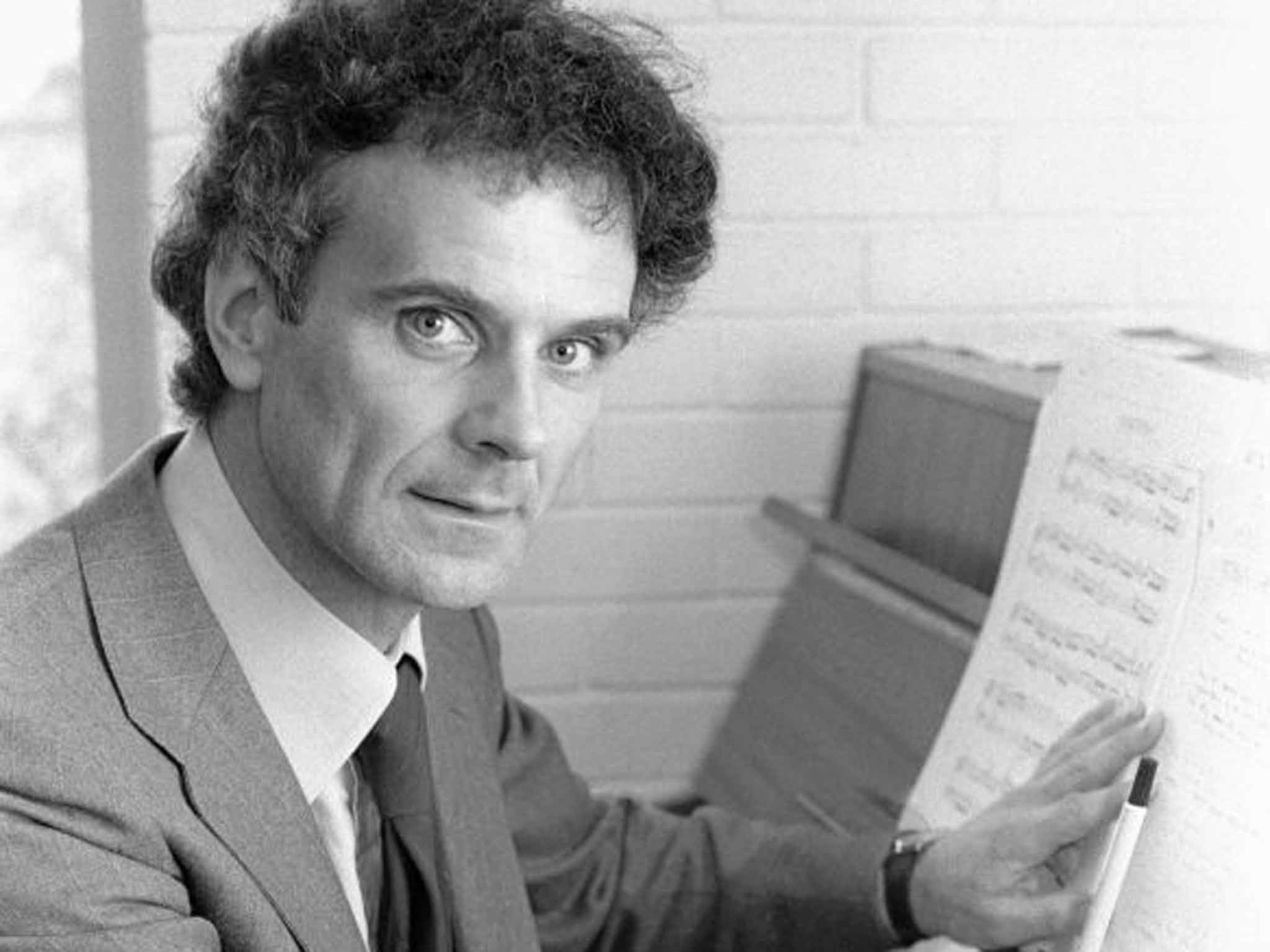

Sir Peter Maxwell Davies: Composer and conductor who set out as an enfant terrible but mellowed after move to Orkney

His sense of social responsibility was threaded through many of his works, touching on issues such as war, the environment and politics, while he had a lifelong commitment to education and wrote much well-received music for young people

With his prolific, wide-ranging and boundary-busting output, the composer Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, who has died of leukaemia at the age of 81, made a profound contribution to music in Britain and beyond. He was an enfant terrible of the 1960s, a successor to the avant-garde generation of Ligeti, Lutoslawski, Berio and Xenakis, but at the same time a composer of a distinctly British hue who later served as Master of the Queen's Music.

He traversed the genres, from symphonies and concertos to opera, choral music and works for the theatre, ballet and film. He was also an experienced conductor, with the BBC Philharmonic and Royal Philharmonic orchestras at home and the likes of the San Francisco Symphony and the Leipzig Gewandhaus abroad.

He was born in Salford in 1934, and attended what is now the Royal Northern College of Music, where he was part of the Manchester School with the likes of Harrison Birtwistle, John Ogdon and Alexander Goehr, and he later studied at Princeton with Milton Babbitt.

He had had an early start in music. When his parents took him to see Gilbert and Sullivan's The Gondoliers at the age of four, he announced that he was going to be a composer. Ten years later, he submitted a piece called Blue Ice to the BBC radio programme Children's Hour. The producer Trevor Hill showed it to the show's resident singer and entertainer Violet Carson, who later found lasting fame as Coronation Street's Ena Sharples. “He's either quite brilliant or mad,” she declared.

Indeed, his early works were noisy and brutalist, featuring twisted takes on early music, or on dance tunes like the foxtrot: one performance featured a soprano dressed in a red nun's habit shrieking through a megaphone, while Eight Songs for a Mad King mixed spoken monologues gabbled by George III interspersed with fragments of Handel's Messiah. Concerts were often punctuated by shouts of “Rubbish!”

One one occasion, after much of the audience had walked out of the premiere of Worldes Blis at a Prom performance in 1969, he let it be known before the second performance that he had made extensive revisions, and he was delighted that critics thought the new version to be greatly improved. It was, of course, the original version unchanged.

Like Eight Songs for a Mad King, much of his early work was first performed by Fires of London, the ensemble he co-founded in 1965 with Birtwistle and others, originally to stage Schoenberg's Pierrot Lunaire. Other Maxwell Davies pieces thus premiered were Vesalii Icones, The Martyrdom of St Magnus, Ave Maris Stella and Revelation and Fall.

A permanent move to the Orkney Islands in 1971 heralded a shift in his musical worldview. The landscape and culture – especially the work of the Orcadian poet George Mackay Brown – had a deep impact on him, and while his music could still possess jagged edges, there was a new-found serenity, though he recalled for a BBC4 documentary in 2013 being described as “a traitor” to the cause of new music because he had allowed tonality into one of his pieces.

He became interested in classical forms, completing his First Symphony in 1976; his Tenth Symphony received its premiere in 2014.He also wrote a Sinfonia Concertante (1982), as well as the series of 10 Strathclyde Concertos for various instruments, highlights of his work with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra between 1987 and 1996). Between 2002 and 2007 he work on a series of string quartets for the Maggini String Quartet to record on Naxos Records (the so-called Naxos Quartets). He viewed the cycle, he said, “as a novel in 10 chapters”.

In 1977 he founded the St Magnus Festival, an annual event with Orkney residents at its heart. What may be his most-heard piece had its premiere during the 1980 Festival: “Farewell to Stromness”, a piano interlude in The Yellow Cake Revue, which he composed following a report that uranium deposits had been found near the Orcadian town of Stromness. It was quite unlike his earlier work, and the Independent music critic Andy Gill described the pieces in the Revue as “simple but deeply satisfying evocations of place, weather and character.”

His sense of social responsibility was threaded through many of his works, touching on issues such as war, the environment and politics. But his playful side was evident when an Independent journalist attempted to contact him at his hotel in Las Vegas in 1995 when he was touring with the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra. He was eventually tracked down, despite the hotel listing him as “Mavis”. He went on to compose Mavis in Las Vegas, which the conductor John Mauceri described as “a totally mad transvestite dream ballet ... a bubble-bath in a heart-shaped jacuzzi”.

Critics were not always kind to his post-1970 output, often deeming it unchallenging and safe, but he was unperturbed, remarking, “I have been criticised a lot for writing in different styles and different kinds of music. I've been called a prostitute. Fine. In that case, so was Mozart.”

He was characteristically ahead of the curve in 1996 when he became was one of the first classical composers to open a download website, MaxOpus – though it would bring trouble when two of MaxOpus's directors were found to have embezzled £450,000 from Maxwell Davies. The site was relaunched in 2009.

He was also ahead of his time in his personal life – at least in Orcadian terms. In 2007 he and his partner Colin Parkinson planned to hold their civil partnership ceremony on Sanday, where they had lived for nine years, accompanied by a piece of music he had written for the event, but Orkney Islands Council ruled that the registrar, a friend of the couple, was not authorised to officiate – though officials also cited fears of a media circus and “unsuitable music” as reasons to move the ceremony.

“Everybody can get married where they live except me, it seems,” he said. “Fundamental religious people, who delve into the Bible to justify their hatreds, still hold great sway. That kind of malignant influence is wrong.”

Knighted in 1987, he was Master of the Queen's Music from 2004 to 2014 – a job, he said, that converted him from a republican into a royalist. “I have come to realise that there is a lot to be said for the monarchy,” he said. “It represents continuity, tradition and stability.”

But though he may have mellowed, the former enfant terrible could still make a noise. A few years ago he suggested that people whose mobile phones go off during concerts should be fined, with proceeds going to the Musicians' Union. He also described taped music in public places as “some kind of commercial and cultural terrorism,” complaining that he had been driven out of a branch of Waterstone's by the music blaring over the shop's loudspeakers.

And when David Cameron appeared on Desert Island Discs in 2014 and chose mostly pop music, Maxwell Davies raged, “In any other European country, a politician who chose that sort of garbage would be laughed out of court. The anti-artistic stance of our leaders gets up my nose. Their main aim is to turn us all into unquestioning passive consumers who put money into the bosses' pockets. That is now the purpose of education.”

He had a lifelong commitment to education himself, and wrote much well-received music for young people; his children's opera The Hogboon will have its world premiere at the Barbican in June with Sir Simon Rattle and the London Symphony Orchestra. In his own appearance on Desert Island Discs he said, “I feel that I want to tell people how it is to be PMD, and I do hope my music reflects something of the spiritual values and helps people to understand their own musicality, their own spiritual development, and that it means something to people's spiritual lives.

“This is terribly important to me. I would hate not to have my pieces played. I would hate not to be able to communicate: it's a love of people, I think, as basic as that.”

Peter Maxwell Davies, composer and conductor: born Salford 8 September 1934; CBE 1981, Kt 1987, CH 2014; died Hoy, Orkney Islands 14 March 2016.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks