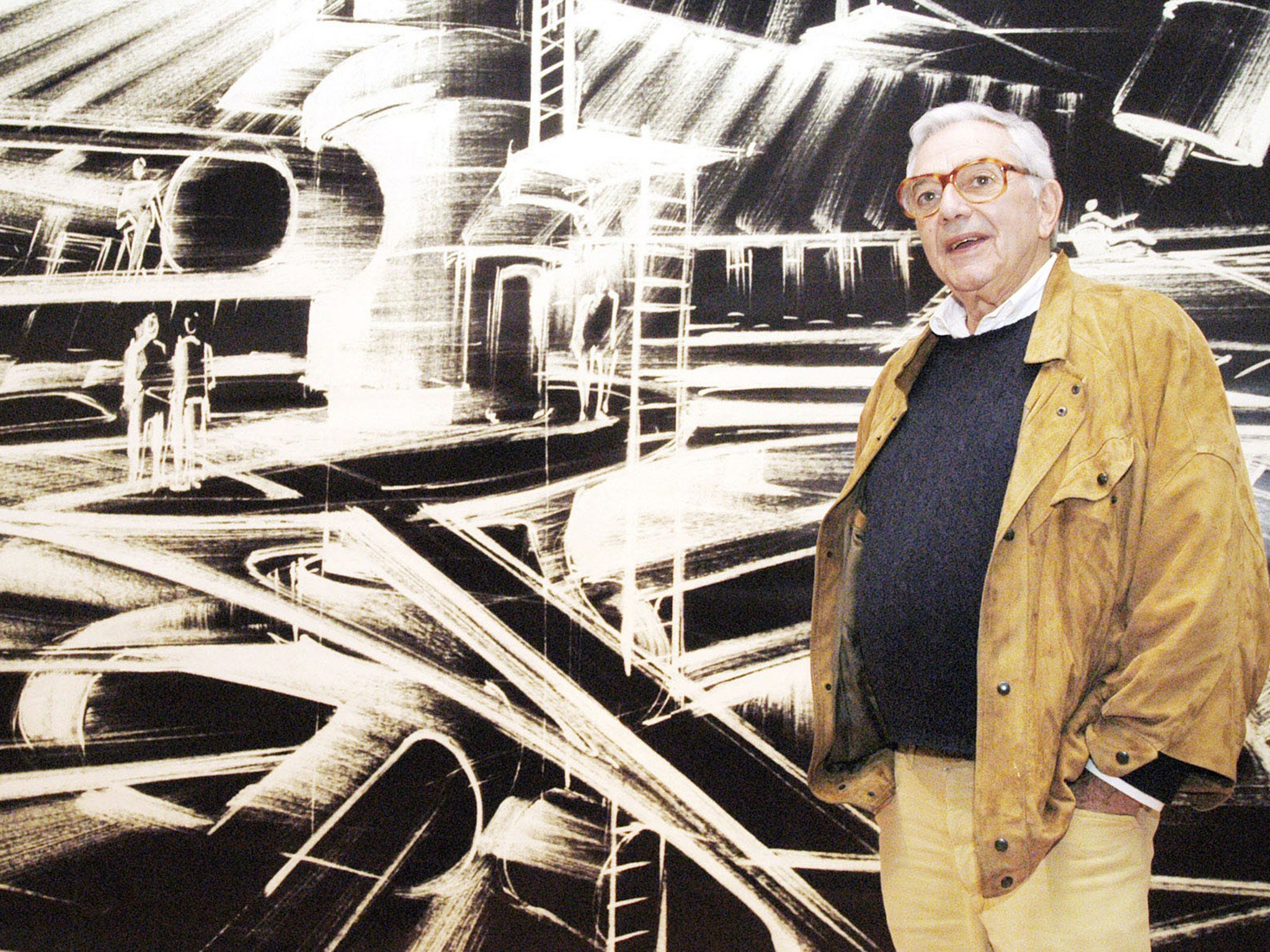

Sir Ken Adam: Oscar-winning designer whose grand sets for the Bond films played a crucial role in their global success

For 1964’s ‘Goldfinger’ he contributed heavily to the design of the now legendary Aston Martin

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In a career that spanned more than 50 years and some 70 films, it will be Ken Adam’s contribution to the James Bond series for which cinema history will most remember him by. Although largely unknown and unheralded by the majority of cinemagoers, we have all seen and been bowled over by Adam’s production design feats, from the war room in Dr Strangelove to the rocket base hidden in a volcano in You Only Live Twice. His expansive visual style was especially suited to the world of 007 and his often grandiose sets, notably those he designed to encumber the villain, became a hallmark of the series

He was born Klaus Adam into a prosperous middle class family in Berlin in 1921. From an early age he demonstrated a talent for art, with a desire to become a painter. Influenced by Bauhaus and Fritz Lang, Adam called the cultural ferment of Twenties Berlin “the foundation of my future education.”

But Adam was also a Prussian Jew, and the Berlin of his youth eventually fell prey to the Nazi jackboot. His father, a decorated cavalry officer in the First World War, was briefly imprisoned, and Adam personally witnessed the burning of the Reichstag. In 1934 the family fled to England, but Adam’s father could never adjust to life in a new country; a broken man, he died of a heart attack in 1936 aged 56.

To enlarge the family coffers, Adam’s mother opened a boarding house for refugees. One visitor, a Hungarian painter, introduced Adam to the film industry, opening up a whole new world of possibilities for him. He set his sights on a career as a set designer, seeing the job as being more than a mere supplier of background scenery, rather someone who could enhance the mood of a scene using visual ideas. On the advice of Vincent Korda he attended evening classes to study architecture.

Narrowly escaping internment as a German national, Adam volunteered for the Pioneer Corps, along with other European émigrés when war broke out. He was 19. Later he was astonished when his application to join the RAF was accepted, and he was sent to Canada to earn his wings. Adam had the distinction of being the only German fighter pilot in the RAF, flying Hawker Typhoons on tank-busting raids in occupied Europe.

In 1946 he was demobbed and went straight into the film business as a draughtsman, working his way quickly up to the position of assistant art director, where his remarkable visual artistry made him much in demand, working on films like Captain Horatio Hornblower (1951) and Around the World in 80 Days (1956).

It was on the recommendation of the producer Albert R “Cubby” Broccoli, who had worked with Adam on The Trials of Oscar Wilde (1960) that the production designer came to work on the first 007 film, Dr No (1962). Broccoli knew Adam was innovative and could work miracles within the film’s meagre budget. Sure enough his stylised, almost surreal creations caught the film-going public’s imagination.

As a result of his Bond work Adam was personally chosen by Stanley Kubrick to design the stark Cold War sets of Dr Strangelove – the BFI described his work as “gleaming and sinister” – and despite an uneasy relationship they collaborated again in 1975 on Barry Lyndon, for which Adam received his first Academy Award.

Working on Dr Strangelove, however, meant missing out on the second, and some say best, Bond film, From Russia With Love. But he was back for the classic Goldfinger (1964), for which he built a replica of Fort Knox and also contributed heavily to the design of the now legendary gadget-laden Aston Martin sports car, with its machine guns, tyre shredder and ejector seat.

As the Bonds met with huge international success the films’ budgets soared, and on You Only Live Twice (1967) Adam spent $1m on a single set, a rocket base hidden inside a dormant volcano. Built on the backlot of Pinewood studios it required 200 miles of tubular steel (more than was required to build the London Hilton Hotel), 200 tons of plasterwork and the services of 250 builders. It was a massive undertaking, one Adam feared that if unsuccessful may have spelled the end of his career. Instead it perhaps remains unsurpassed as a production design feat.

In The Spy Who Loved Me (1977), Adam’s spectacular sets similarly dominated the film. His pièce de résistance this time was the interior of a supertanker big enough to swallow three nuclear submarines. The tanker set was so large in concept that it required it’s own specially constructed soundstage at Pinewood: christened the 007 stage it remains one of the biggest of its kind in the world.

Adam’s final Bond film was Moonraker, for which he based his space station designs on extensive research he carried out at Nasa. After that he worked almost exclusively in the US, on films such as The Freshman and Addams Family Values, though he continued living in his Georgian home in Knightsbridge with his Italian-born wife Letizia, an advertising art director whom he had met on location in 1952.

In 1994 Adam won his second Oscar, again for a period film, this time The Madness of King George. For years it was a matter of frustration that his futuristic design for the Bond films failed to gain the same kind of critical recognition. Some recompense arrived in 1999 when he was fêted with an exhibition of his production art at London’s Serpentine Gallery. He also returned to Berlin to mastermind the construction of the city’s millennium project.

Adam’s contribution to the emergence of the James Bond series as a pop culture triumph in the 1960s cannot be ignored. In 2012 he handed over his entire body of work to the Deutsche Kinemathek – around 4,000 sketches, photographic albums, storyboards, memorabilia, military medals and identity documents as well as all his awards, including his two Oscars.

He was deservedly presented with an honorary doctorate from the Royal College of Art, whose professor, Christopher Frayling, called him “a key contributor to 20th century visual culture”.

Klaus Hugo Adam (Ken Adam), film production designer: born Berlin 5 February 1921; OBE 1995, Kt 2003; married 1952 Maria-Letizia Moauro; died London 10 March 2016.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments