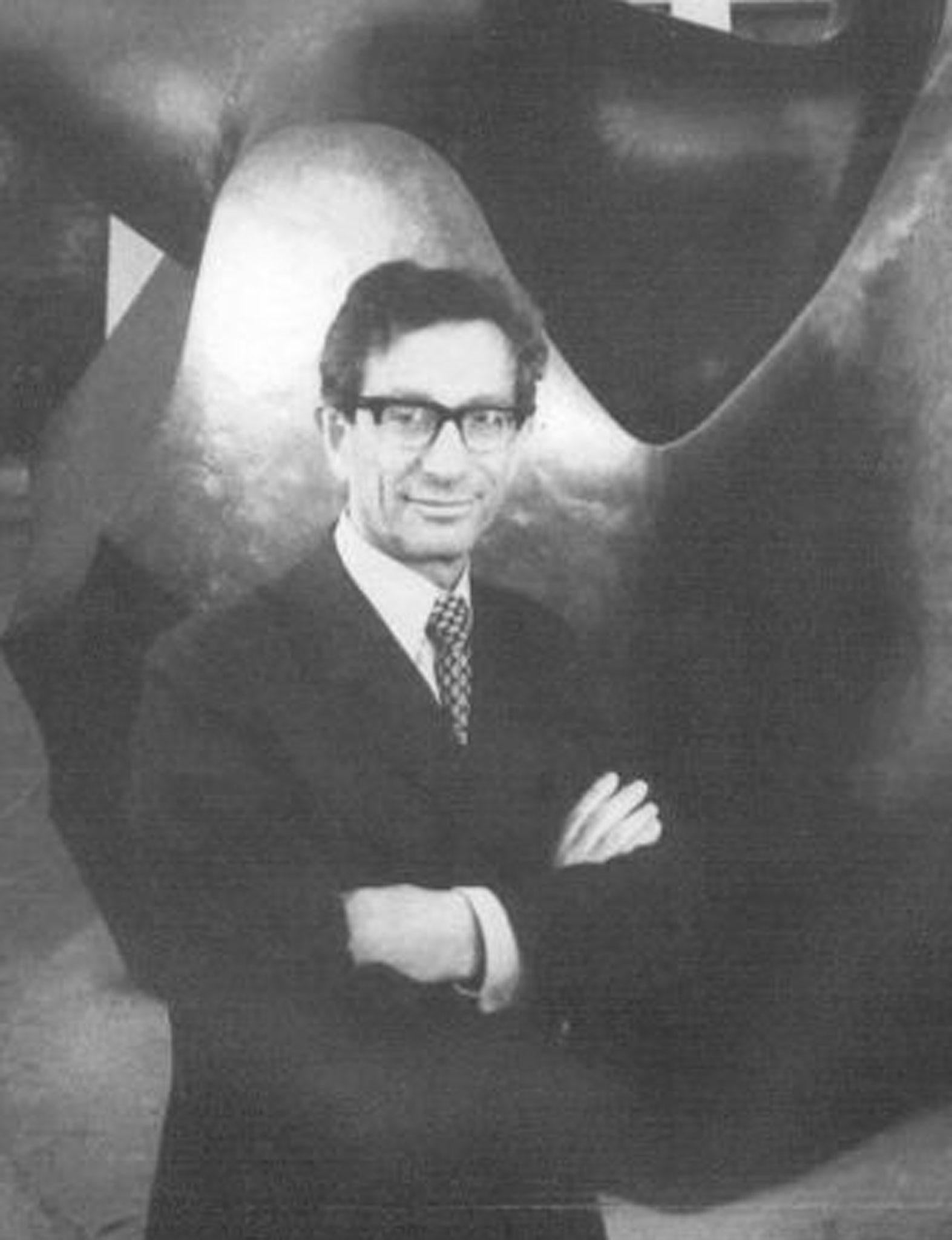

Sir John Burgh: Senior civil servant and leader of the British Council

‘His judgement was excellent,’ Shirley Williams said of him. ‘He rang true on everything’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.John Burgh, an Austrian Jewish refugee who arrived in this country in 1938 at the age of 13 unable to speak a word of English, went on to become the head of the organisation responsible for promoting British culture to other countries, having risen through the ranks of the Civil Service to work for some of this country’s leading cabinet ministers. He would also become President of Trinity College, Oxford.

Burgh was brought up in Vienna, his father a barrister who died when John was 11. He retained a lifelong memory of looking down on the main avenue from his flat in Vienna after the Anschluss and seeing Hitler standing in his car driving along with his arm up making the Nazi salute: “I can still see him, with all the cheering and jubilation.” His family background had been cultured and musical, with both his parents playing instruments and Burgh playing the piano; all that was to come to an end, though music would remain an essential part of his life.

With the help of the Quaker Movement Burgh and his sister Lucy fled to Britain in late 1938. His mother, who had had her children baptised into the Church of England in the belief that it would help them to escape, followed them six months later; both sets of grandparents and other members of the family perished.

He went to the Friend’s School in Sibford, leaving in 1941 aged 15, having become fluent in English and sailed through his exams. Piano lessons, though, were curtailed through lack of money. He worked in aircraft factories until the end of the war, when he returned to his studies. He decided to study economics, believing that the discipline could answer the world’s problems – later he said experience had shown him otherwise – and entered the London School of Economics as a night student, teaching during the day. Harold Laski, under whom he studied, helped him to win a bursary so he could study full-time. In his second year he became President of the Students Union; years later he would become Chairman of the Governors.

It was at LSE that he and a group of friends founded a group called The Seminar which continued to meet once a week for the next 40 years. Having lost his family during the war, Burgh gathered friends about him.

The proximity between the college and Covent Garden meant he was able to sit in the gods and watch operas, never expecting that one day he would become secretary of the Opera co-ordinating committee, and in 1991, its chairman. His love of music saw him taking on a range of administrative posts: in 1994 he became vice-chairman of the Yehudi Menuhin School. He played the piano weekly in a duet with friends, the last a clarinettist, until his death.

Not wishing to work for a profit-making organisation, he entered the administrative branch of the Civil Service. Over the next 30 years he served in several ministries, becoming Private Secretary, Under Secretary and Principal Private Secretary to a number of ministers including George Brown at the Department of Economic Affairs, Barbara Castle as she worked through In Place of Strife at the Department of Employment, and with her Conservative successors Robert Carr and Geoffrey Howe as they implemented new trade union laws. Having spent years trying (by his own account) to leave the Civil Service, he was seconded in 1972 to become Deputy Chairman of the Community Relations Commission, but returned two years later to join the Cabinet Office as its deputy secretary in charge of a new think tank, the Central Policy Review Staff.

His last Civil Service position was working for Shirley Williams, who became a close friend. His appointment as her Deputy Permanent Secretary was one of her conditions for agreeing to head the newly constituted Department of Prices and Consumer Protection. The Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, told her she had made a good choice. “Burgh’s name,” Williams told me, “was a byword for integrity. He was a wonderful man, serious, but with a wryness and touch of irony. His judgement was excellent – he rang true on everything.”

In 1980 he finally left the Civil Service to become Director of the British Council, the body responsible for promoting British values, language and culture abroad. Morale at the time was low with the Council having undergone a number of cuts. Burgh dispelled the apathy, reaching out to the workers in the “engine room”, meeting them in the canteen, touring around talking to them. He was rewarded for his work with a knighthood.

In 1987 he became President of Trinity College Oxford, a position he held until 1996. Never scared of confronting difficult issues, he supported Dignity in Dying; his sister, diagnosed with terminal cancer, committed suicide, as did his sick brother-in-law. He believed it was important to have freedom of choice to decide when you wanted to die. In 1984 he appeared on Desert Island Discs; asked what he would like as his luxury, he replied that he wanted a transistor radio so he could listen to more music. Plomley allowed him to take it, a rare case of flouting the rules.

Sir John Burgh, civil servant and public servant: born Vienna 9 December 1925; CB 1975, KCMG 1982: married 1957 Ann Sturge (two daughters); died 12 April 2013.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments