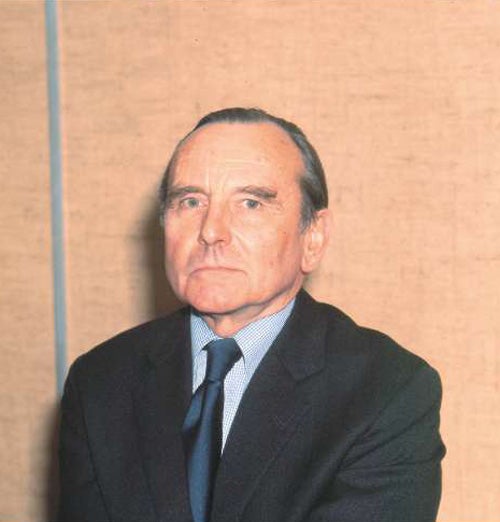

Sir Geoffrey Cox: War reporter, diplomat and soldier who became a founding father of television journalism

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Geoffrey Cox, war correspondent, Chief Intelligence Officer of the New Zealand Army, diplomat, assistant editor of the News Chronicle and writer, became one of the founding fathers of television journalism. He was Editor of Independent Television News from 1956 to 1968 and started News at Ten in 1967. Later he was Deputy Chairman of Yorkshire Television, and Chairman of Tyne Tees Television and of the London radio news station LBC.

A convivial and highly intelligent man, Cox was also a brave and resourceful correspondent. In 1932 he had entered Oriel College, Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar from New Zealand, where he had gained a first class degree in History from Otago University. At Oxford he read Philosophy, Politics and Economics and travelled widely in Europe during the vacations. Challenged by a German Rhodes scholar in 1934 to see the true face of Nazism, Cox served for three weeks in the Arbeitsdienst, the Nazi youth service, draining marshes and drilling with spades instead of guns. An article he wrote on the German labour camps led the Sunday supplement of The New York Times and was also printed in The Spectator. This in turn helped him to secure a reporting job on the News Chronicle.

In 1936, when the Spanish Civil War broke out, Cox was sent to cover the heroic resistance of Madrid. His experiences there provided a short book, Defence of Madrid (1937), and led to an offer from Arthur Christiansen to join the Daily Express as a foreign correspondent, first in Vienna and later in Paris. From there he covered the start of the Second World War, moved on to Holland for the invasion scares in the winter of 1939-40, and to Finland for the Russo-Finnish Winter War. He reported the invasion of Belgium and the fall of France, and returned to England in June 1940 by the last passenger ship to leave Bordeaux. He recorded this eye-witness experience of the gradual slide into Armageddon in his 1988 book Countdown to War.

Cox then decided that he had had enough of writing about wars; it was time to start fighting them instead. He joined the New Zealand 5th Infantry Brigade, which had been diverted to England from the Middle East, was commissioned, served in Greece and Crete, and in the Western Desert. For his work as Intelligence Officer on General Bernard Freyberg's staff in the battle of Sidi Rezegh in 1941 he was mentioned in despatches.

In 1942 New Zealand began to create its first diplomatic service. Cox was plucked from the desert, put into mufti and made First Secretary of the newly established Legation in Washington. The Minister of the Legation, Walter Nash, was also New Zealand's Minister of Finance, so Cox was often in charge for long periods. I was then attached to a British government mission in the United States and it was there that I first got to know Geoffrey Cox. He was a trim, dark-haired, shortish man with a clipped New Zealand accent and a twinkle in his eye. At the age of 32 he represented New Zealand on the Pacific War Council, the supreme political body overseeing the war in the Pacific, with President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the chair.

After two years as a diplomat Cox rejoined the New Zealand Division at Cassino and served in Italy until the end of the war as Chief Intelligence Officer to General Freyberg. Again he was mentioned in despatches and appointed a military MBE. His book The Race for Trieste, published in 1977, is a key work on the clash with Tito at the end of the European war.

When he was demobilised Cox returned to the News Chronicle, first as its Lobby Correspondent. He also broadcast frequently on the BBC World Service and wrote scripts for the cinema documentary series This Modern Age, J. Arthur Rank's answer to The March of Time. Next he began to make appearances on BBC television as one of the panel of journalists in Press Conference. In 1954 he interviewed the Chancellor of the Exchequer, "Rab" Butler, and the Leader of the Opposition, Clement Attlee, on the Budget, the first time this was done on television.

The following year, when the newspapers were off the streets for three weeks, I organised a nightly discussion television programme for a panel of journalists to report on and discuss the news they would have written for their papers. By that time Cox had become Assistant Editor of the News Chronicle and he was a member of this panel. The experience taught him how to put his own views forward on the air. Later in 1955 he helped to edit and present the Conservative and Labour conferences for BBC Television.

The rival presenter of the political conferences for Independent Television, which had opened in the London area a few weeks earlier, was Aidan Crawley, the first Editor of ITN. His competitive news service had won acclaim from the outset for its fresh approach and the use of personality newscasters. However the commercial programme companies, whose initial costs were far outstripping their revenues, soon wanted to prune ITN drastically, both in finance and air-time, reducing it to little more than a daily headline service.

Crawley resigned in protest, in January 1956, when ITN had only been on the air for five months, but in the process he won for ITN the protection of a ruling from the Independent Television Authority that there must be a minimum of 20 minutes of news a day. Cox was appointed in his place and remained Editor of ITN until 1968. It was a formative period for television news, not only in Britain, but throughout the Western world, and Cox played an outstanding part in its development. He was the founding father of British electronic journalism.

ITN with its strong team of newscasters, its lively reporting and its excellent film work easily dominated television news until 1960 when the BBC's lacklustre Editor of News, Tahu Hole, another New Zealander, was replaced. From then on, vigorous competition provided British viewers with continuing high standards. During the Rochdale by-election in 1958 Cox pioneered the reporting of a British election campaign.

Cox resolutely resisted all attempts by pressure groups to manage the presentation of television news. At the 1958 Conservative Party Conference in Blackpool it was still necessary for the film shot by both ITN and BBC to be flown to London in the late afternoon for processing and editing. We shared the costs of a chartered plane. Those organising the timetable carefully arranged that the controversial debate on law and order, at which the hangers and floggers in the Tory party had their say, should take place after television had to cease filming for the day, for they did not want the unedifying aspects of the debate to be shown. Cox saw through this ploy. I accepted his suggestion that we should go halves in chartering an extra plane on that day for a last-minute addition, and the attempted news management was frustrated.

He played a leading role in establishing News at Ten, the first half-hour news on British prime-time television. The newscasters he recruited included Sir Alistair Burnet, Sir Ian Trethowan, Sandy Gall, Peter Snow, Andrew Gardner and Peter Sissons.

In 1968, when the new Yorkshire ITV area was created, Cox went to Yorkshire Television as Deputy Chairman. Three years later, when Tyne Tees and Yorkshire were linked in Trident TV, he went to Newcastle as Chairman of Tyne Tees TV. He loved the North East and his years there were happy ones. In 1976, on retiring from television, he became the Chairman of LBC, the former London all-news radio company.

Cox was appointed CBE in 1959 and knighted in 1966. He was awarded both the Gold and Silver medals of the Royal Television Society and in 1962 won a Bafta award for television journalism. He and his wife Cecily, whom he met as a student at Oxford, moved to the Cotswolds in 1977, and he became an active member of the Council for the Protection of Rural England. After her death in 1993 he produced a revised edition of his 1983 history of ITN, See it Happen. He wrote two more books, Pioneering Television News (1995) and Eyewitness: a memoir of Europe in the 1930s (1999).

Leonard Miall

Sir Geoffrey Cox was the last survivor of an extraordinary group of young New Zealanders who were at Oxford and Cambridge during the 1930s, writes Michael Fathers, and who made a deeper mark on Britain and abroad than they could ever have made in their own dour and insecure country where tall poppies, especially clever and opinionated ones, tended to be cut down before they bloomed.

Such was their influence at Oxford that Australians in particular and some British academics complained about a "New Zealand Mafia" and its widespread tentacles. No other generation in New Zealand has produced such an intense flowering of talent. This group of some dozen young men were anti-fascist, a couple being self-declared Communists and Marxists. They were all excellent linguists.

Cox and his Oxford colleague the classicist Dan Davin and Paddy Costello from Cambridge went through the Second World War as intelligence chiefs with General Sir Bernard Freyberg and the New Zealand "Div" in the 8th Army. Others, John Mulgan and Norman Davis, were involved in SOE operations in Greece and the Balkans. Another, James Bertram, followed the American journalist Edgar Snow into Yennan to interview Mao Tse Tung and became an envoy of Madame Sun Yat Sen. Two of the group became diplomats, Ian Milner, as a founding staffer at the newly created United Nations; the other, Costello, to open New Zealand's first diplomatic mission in Moscow.

Geoffrey Cox was the most down-to-earth and focused of the group. Ambitious, and single-minded in his determination to be a journalist, he spent his summer vacations in Germany and Austria in 1932, 1933 and 1934, learning German and writing his first article about attending a Nazi student work camp in Hanover. He helped drain a swamp which he later believed was being made ready as an airstrip for the Luftwaffe and learned how to throw mocked-up hand grenades during sports.

Back in London, he scoured Fleet Street in search of work. Throughout his post-war career he would always seek to accommodate any journalist, especially a newly arrived New Zealander, who came knocking at his door in London looking for holiday relief work.

As Paris correspondent of the Express from 1938 he covered all the major events in Europe leading up to the Russian invasion of Finland and the defeat of France in 1940. Annoyed by Cox's anti-appeasement views, Beaverbrook originally wanted him out and ordered him back to London.

At a meeting in 1938 at the Ritz Hotel in Paris between His Lordship and his correspondent, Beaverbrook listened to Cox's plea to stay and issued one of Fleet Street's more infamous memos, to the editor of the Express. With Cox listening he spoke into the trumpet of his dictation machine: "Message for Arthur Christiansen. Cox does not want to be a leader writer (in London). Better let him ride," After Cox had thanked him and left the room, Beaverbrook added another sentence: "Sack him within a month".

Geoffrey Sandford Cox, journalist, broadcaster and writer: born Wellington, New Zealand 7 April 1910; reporter, News Chronicle 1935-37, Political Correspondent 1945-54, Assistant Editor 1954-56; reporter, Daily Express 1937-40; First Secretary and Chargé d'Affaires, New Zealand Legation, Washington 1943; MBE (mil) 1945; Editor and Chief Executive, Independent Television News 1956-68; CBE 1959; Kt 1966; Deputy Chairman, Yorkshire Television 1968-71; Chairman, Tyne Tees Television 1971-74; Chairman, LBC Radio 1978-81; CNZM 2000; married 1935 Cecily Turner (died 1993; two sons, two daughters); died Stonehouse, Gloucestershire 2 April 2008.

* Leonard Miall died 24 February 2005

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments