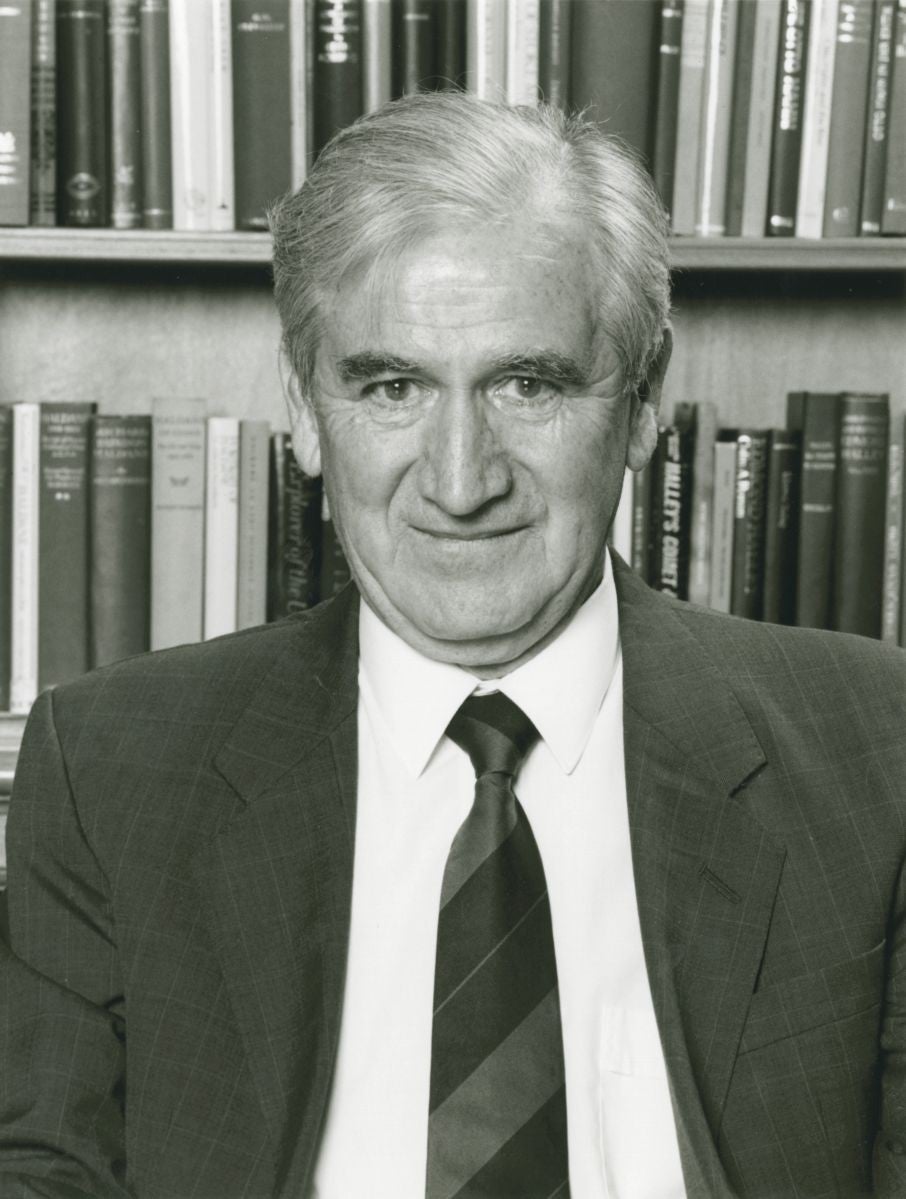

Sir David Jack: Pioneering chemist who revolutionised the treatment of asthma

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The three great names in British drug development for the past half century had the euphonious names of Jack, Black and Vane; and while Sir David Jack was the only one not to win a Nobel Prize this was largely due to chance, as his discoveries were equal to those of Sir James Black and Sir John Vane. Jack's contribution, with his team, was to develop the first inhaled asthma medicine, salbutamol (Ventolin). It relieved the wheezing of asthma almost instantaneously by going straight to the lungs, and only atiny dose was needed as it was not dispersed around the rest of the body. Previously, patients had to take ephedrine or similar compounds, wait up to half an hour for the drug to be absorbed, and put up with several hours of the tremors and palpitations that were the inevitable side-effects.

Salbutamol was launched in 1969 and decades later it remains one of the most commonly prescribed of all medicines and has saved many lives. It was the first drug of a kind called beta-2 selector agonists, meaning its action resembled the beta-2 actions of histamine, but not the beta-1 actions on the heart. Barry Kay, Emeritus Professor of allergy and immunology at Imperial College and the Royal Brompton Hospital said of him, "In the field of asthma especially, his work revolutionised treatment by targeting muscle spasm and inflammation in the bronchi [breathing tubes] so improving the quality of life for millions of sufferers".

Salbutamol, however, was active for only a short duration and Jack's team followed it with a long-acting analogue, salmeterol. Having established that the best way of delivering asthma drugs was by inhalation, he went on to produce an inhaled steroid, beclomethasone (Becotide) which counteracted the inflammation that underlies asthma, and fluticasone, a synthetic steroid to rival beclomethasone. He also formulated fluticasone as a cream for eczema treatment. Other successes included the first good anti-migraine drug sumatriptan (Imigram) and the anti-emetic ondansetron (Zofran) used to treat chemotherapy nausea.

Jack was the sixth and youngest child of a mining family in Fife, not far from James Black, who was born in the same year. The two men became lifelong friends. Jack won a place at Buckhaven high school and, rejecting the chance to study maths at Edinburgh University, joined Boots as an apprentice pharmacist. After qualifying he attended Glasgow Royal Technical College – now Strathclyde University – graduating in 1948 with first class honours. He turned down the chance to study for a PhD to become, briefly, assistant lecturer in pharmacy at Glasgow University.

After national service, teaching in the army's school of health, he joined the pharmacy research department of Glaxo. His job was to formulate new medicines and supervise their transfer to production. He found this repetitive and unfulfilling. After two years he moved to Menley & James, which was taken over by Smith Kline and French, where he developed waxes used for coating tablets. During this time he developed his chemistry interest, taking a part-time PhD at Chelsea Polytechnic under the eminent pharmaceutical chemist Arnold Beckett.

In 1961 he was invited to Allen & Hanburys, by now part of Glaxo, as research and development director, and it was there he did his finest work. When he joined, it was a small company best known for its blackcurrant pastilles and Glaxo, for its infant formula. Jack felt they should focus on serious illnesses that affected masses of people. The drugs he developed turned the group into an international giant.

With a view to the wider good and the wider market, Jack focused on asthma, high blood pressure and ulcers. When his friend and rival James Black of Smith Kline and French published a paper in Nature showing that chemicals called H2 antagonists could switch off acid secretion in the stomach, he recognised this as a potential treatment for acid reflux and peptic ulcers, hitherto treatable only by antacids, surgery and a bland diet (the latter recommended despite overwhelming evidence of its uselessness.)

The race to produce the first anti-ulcer drug was won by SKF with Tagamet (cimetidine) in 1978. It needed to be taken four times a day. Jack's team raced to produce a rival, Zantac (ranitidine) which came to market three years later. Effective in a smaller dose, it needed to be taken only twice daily. Both drugs can now be bought over the counter. Jack, gracious in victory, acknowledged that the breakthrough was his rival's and that he had merely improved on it. He remained at Allen & Hanburys until he retired in 1987.

He received many honours including fellowships of the Royal Society and the Royal Pharmaceutical Society. He was made CBE in 1982 and knighted in 1993. The citation that went with his 2006 royal medal for the Royal Society of Edinburgh named him as one of the world's most successful inventors of significant new medicines.

Jack was passionate about science and had the courage to speak up about the need for animals in research. Barbara Davies of Understanding Animal Research said, "He had started as chair around 1988, when we were called the Research Defence Society, with the remit of reviving it. Apart from lobbying around the 1986 Act, the organisation had not been active for many years. The antivivisection groups were jumping on the green bandwagon and also propagating the new ideology of animal rights. David Jack employed a new director and together they worked on a business plan and raised funds to get RDS back on its feet to fight the renewed antivivisection threat to research. He employed me in communications, and experts in science and education at a time when 'defending' animal research was deeply unfashionable."

After his retirement Jack joined a small innovative drug-development company, where he continued to work on new asthma drugs, one of which is in clinical trial. He was a genial man, much liked, and caring towards his staff and students; his recreations were theatre-going, gardening and golf.

Caroline Richmond

David Jack, pharmacologist: born Markinch, Fife 22 February 1924; CBE 1982, Kt 1993; married 1952 Lydia Brown (two daughters); died 8 November 2011.

22.02.1924

On the day he was born...

The US president Calvin Coolidge became the first politician to deliver a speech on the radio.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments