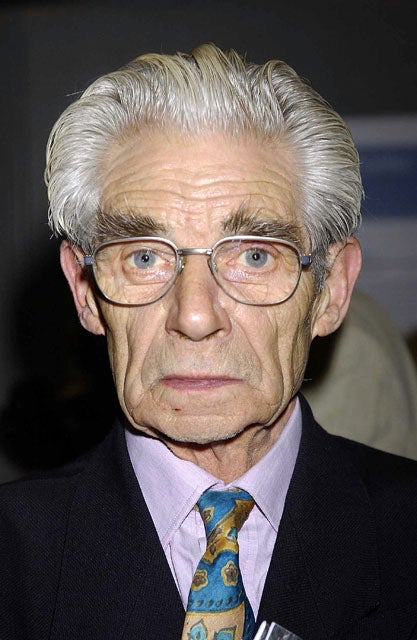

Sir Charles Wheeler: Distinguished foreign correspondent who exemplified the best in BBC reporting for more than 60 years

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the comparatively brief history of broadcasting, only a handful of news correspondents have become household names. Charles Wheeler, knighted in 2006, was incontestably one of them. In a career with the BBC that lasted more than 60 years, he reported from the most troubled and significant parts of the world with measured judgement and sometimes laconic aplomb that listeners and viewers found reassuring, however dire the story he was obliged to tell.

He seldom employed superlatives, believing fervently that the reporter's job was to remain a detached observer on the sidelines. It was for this reason that a 2004 BBC profile of him was subtitled "Edge of Frame". Richard Tait, a former editor of BBC2's Newsnight – a programme with which Wheeler was associated – said in 1993: "Charles is one of the greatest broadcasting journalists of the television age." Yesterday Mark Thompson, director-general of the BBC, praised "his integrity, his authority and his humanity". John Tusa, another former colleague, commented: "He didn't tart it up with fancy words and didn't strike postures. . . He wanted you to know and hear and see what was going on."

Wheeler's career spanned what many now regard as the golden ages of both radio and television news. He was equally at home on both, distinguished by his silvery voice – clipped, precise but in no way affected – and, in later years, by his shock of thick, white hair.

He was born Selwyn Charles Cornelius-Wheeler in Germany in 1923. His father was a shipping agent in Hamburg and he spent much of his boyhood there, watching the inexorable rise of the Nazis. He was educated at Cranbrook School in Kent, leaving at 17 because he was attracted by what he saw as the glamour of journalism.

His first job was on the tabloid Daily Sketch, where his principal task was to rip news-agency reports from teleprinters and rush them to the editors' desks. In 1943 he joined the Royal Marines and, because he spoke fluent German, was soon recruited by the special intelligence unit formed by Ian Fleming (later the creator of James Bond), playing an important role in the preparations for the D-Day landings. Sixty years later he went back to the Normandy beaches to take part in a BBC documentary commemorating the anniversary.

In the aftermath of the Allied victory he was assigned to Berlin, where his job was to make sure that German officers with technical know-how, such as U-boat commanders, did not end up in the Soviet zone. In 1947 he joined the BBC Overseas Service as a sub-editor on the Latin American desk and after three years he was given his first reporting assignment, as a correspondent for the German service in Berlin.

There, as he revealed to The Independent in 1997, he continued his relationship with the security services. They would give him information gained from sources in the east, which he would use in his broadcasts, and in return he would share snippets from his own sources. "It was all done on an old boys' basis," he said. "I knew that the stuff I was sending back was being used in the propaganda broadcasts into eastern Europe. That was the job in those days. That didn't mean it was lies. . . I suppose I was a Cold War warrior."

In 1956 he moved to television as a producer on Panorama, the long-running current affairs programme. Almost as soon as he arrived, he was involved in a controversy when he arranged a studio interview with Brendan Behan, the Irish playwright, who was palpably drunk after an extended visit to the hospitality room. Wheeler was threatened with disciplinary action but was reprieved when he explained that he had prevented a worse fiasco by pouring the reserve stocks of whisky and gin down the sink.

One of his earliest successes on Panorama was to get a camera into Hungary to cover the ill-fated anti-Soviet uprising, sending the film back to London every day through Austria. But as Michael Peacock, his fellow producer, recalled in 1993: "Producers are midwives and he is not a natural midwife. He was put on earth to be a reporter, to make sense of the world. He wanted to get as close as he could to events."

So in 1958 he left the programme to return to his more natural role. His first assignment was as South Asia Correspondent, based in Delhi. There he met Dip Singh, whom he married in 1962 after the failure of his first marriage, which he was always reluctant to discuss. He and Dip had two daughters – one of whom, Marina, is married to Boris Johnson, the Mayor of London.

The year of his marriage saw him posted back to Berlin – with the Cold War at its height – and in 1965 he went to Washington, which was in many respects the high point of his career. He stayed there until 1973, embracing turbulent times that included the assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, civil-rights campaigns and protests against the Vietnam war, culminating in the Watergate affair. His cool, reflective coverage of these sensational events cemented his reputation and contributed greatly to Britain's understanding of our seemingly headstrong transatlantic cousins.

Wheeler became European correspondent in 1973 and for the next 30 years he enjoyed what was in effect a wandering brief, making countless series and single programmes about the world's most important people and places, collecting numerous industry awards along the way. His reporting of the plight of Kurdish refugees from Iraq, during and after the 1991 Gulf War, won particular acclaim.

Although for the most part a man of modesty and courtesy, he did not mince his words when it came to issues on which he had strong feelings. He was famously out of sympathy with the guidelines for news coverage promulgated by John Birt, the future director-general of the BBC, when he was deputy director-general in 1990. Wheeler was then working on BBC2's Newsnight, and the techniques employed by its interviewers were singled out by Birt for criticism.

"You would have thought they would have consulted some of us before drawing it up," Wheeler complained in an interview. "We don't need to be told to be polite. We don't need to be told to be searching. Anyone who did need to be told those things wouldn't have done more than one interview."

And in a fractious meeting with Birt and his colleagues, who were calling for more analysis in Newsnight, Wheeler fumed: "Can you spell out precisely what form your idea of analysis would take and how it would contrast with what we are now doing?" Any other BBC employee might have thought twice before making such an assault on the senior management, but such was Wheeler's reputation that he was effectively unassailable, and he continued to snipe away at the Corporation's changing culture, saying in 2000 that the news agenda was far too influenced by personalities and the tabloid culture. He was still making superb programmes in his eighties .

Michael Leapman

Charles Wheeler was, quite simply, the best news correspondent the BBC has employed during its 85 years of existence; which was only fitting, given that he and it were almost exactly the same age, writes John Simpson.

He possessed in large measure the finest qualities of a first-rate foreign correspondent: clarity and calmness of judgement, sharpness of vision, breadth of understanding, and a lively interest in the world. An instinctive radicalism of approach, too. This had nothing to do with his personal politics (whatever they might have been; after working alongside him for years, I still have no idea how he voted), and everything to do with an instinctive alignment with the poor and weak against the powerful.

The grandeur of his reputation made ambassadors and cabinet ministers of many different countries rise deferentially when he came into the room, yet he never turned into an establishment figure. He was always an outsider, looking quizzically at the world from under those expressive bushy eyebrows of his. The magnitude of the events he reported on never interested him as much as the effects on ordinary people.

Some of his finest reporting was done in 1991, when he was in his late sixties. He went to northern Iraq and then on to Kuwait for Newsnight in the final stages of the first Gulf War. On a bitterly cold hillside he interviewed two Kurdish refugees, whose articulate, bitter, bewildered plea for help made people in the BBC newsroom weep openly when it was broadcast.

A second unforgettable broadcast came soon afterwards, when he went to Kuwait to investigate reports that some Kuwaiti doctors, returning from exile, were using their medical skills to torture people who had collaborated with the Iraqi invaders. Charles and his crew headed for the ward where these things were happening, and, in the finest foot-in-the-door tradition, he refused to go away until the doctor who had answered his knocking admitted, on camera, that prisoners were indeed being tortured there.

Charles Wheeler's judgements could be very fierce, but that was in private. "I think you could afford to leave that last sentence out," he once said to me when I shared an office with him in Brussels in the 1970s, and showed him a despatch on something I felt strongly about. "The audience will come to the same conclusion without needing to be told."

He was the last, best exemplar of a magnificent tradition.

Selwyn Charles Cornelius-Wheeler (Charles Wheeler), journalist and broadcaster: born Bremen, Germany 26 March 1923; sub-editor, Latin American Service, BBC 1947-49, German Service correspondent 1950-53, Talks writer, European Service 1954-56, Producer, Panorama 1956-58; South Asia Correspondent 1958-62, Berlin Correspondent 1962-65, Washington Correspondent 1965-68; Chief US Correspondent 1969-73, Chief Europe Correspondent, 1973-76, Chief Correspondent, BBC Television News 1977, Chief Correspondent, Panorama 1977-79, Chief Correspondent, Newsnight 1980-95; CMG 2001; Kt 2006; twice married, secondly 1962 Dip Singh (two daughters); died London 4 July 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments