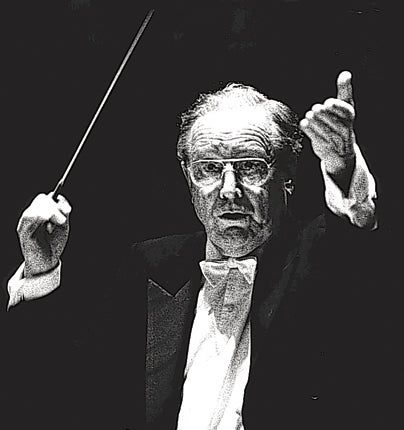

Sir Charles Mackerras: Energetic and perceptive conductor celebrated in particular for popularising the works of Janacek

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Just under two years ago, Signum Classics released a live recording of Schubert's Ninth Symphony, the "Great C major", with Sir Charles Mackerras conducting the Philharmonia Orchestra – a performance which discovered unsuspected depths of primal violence in what had seemed an amiable classic. Mackerras' recordings with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra of Mozart's last four symphonies, released by Linn Records around the same time, likewise came with the force of revelation; and a new Mozart set from Linn, including the Paris, Haffner and Linz Symphonies, which he recorded with SCO in Glasgow last summer, is currently pulling in reviews of astonished admiration. Mackerras' music-making in old age was even more energetic and perceptive than before.

Charles Mackerras was born in Schenectady, New York, but only because his father was doing post-graduate work there: the family returned to Australia, to Sydney, when Mackerras, the eldest of seven children, was two. He retained his links with Australia all his life. After a Sydney schooling, he studied oboe, piano and composition at the New South Wales State Conservatorium of Music.

In his later teens he was playing occasional concerts with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, and in 1943 was appointed principal oboe. He was to retain his association with the orchestra for over 60 years, serving as its chief conductor from 1982 to 1985 – the first Australian to hold the post. In 1973 he conducted a gala concert to open the Sydney Opera House.

In 1946 he took a boat to Britain and the following year won a British Council scholarship to study conducting with Václav Talich in Prague. What changed his life in the Czech capital, and with it the history of music, was his discovery of the music of Leoš Janácek, then hardly known outside Czechoslovakia but now – largely through Mackerras' pioneering efforts – recognised as one of the most original, creative voices of the 20th century.

Back in London in 1948, Mackerras became a staff conductor at Sadler's Wells, making his London operatic debut there with Die Fledermaus (symptomatic of a fondness for operetta that would soon reveal its importance) and remaining on the staff until 1954. Janácek was soon in the repertoire: Mackerras conducted the UK premiere of Káta Kabanová, the sixth of Janácek's nine operas, in 1951 – an engagement with the work which endured. He published a critical edition of the score 41 years later.

Another landmark event in 1951 was the premiere of Pineapple Poll, the ballet Mackerras arranged from Arthur Sullivan's music. He had sung Gilbert and Sullivan operettas as a schoolboy and took Manuel Rosenthal's Gaité Parisienne, a ballet arranged in 1938 from Offenbach's tunes, as a model, producing a work that enjoyed similarly instant success. In 1954 he rendered Verdi the same service, with the ballet The Lady and the Fool.

Pineapple Poll opened doors for Mackerras as a conductor. He was principal conductor of the BBC Concert Orchestra from 1954 to 1966, first conductor at the Hamburg State Opera from 1966 to 1969 and musical director of Sadler's Well (rechristened the English National Opera) from 1970 to 1977 and of the Welsh National Opera from 1987 to 1992. His principal guest conductorships included the BBC Symphony Orchestra (1976–79), Royal Liverpool Philharmonic (1986–88), Scottish Chamber (1992–95), Royal Philharmonic (1993–96), the San Francisco Opera (1993–6), Czech Philharmonic (1997–2003), St Luke's, New York (1998–2001) and the Philharmonia (from 2002). He also held a lengthy chain of honorary positions and was a regular guest at the Royal Opera House and Metropolitan Opera.

Mackerras held countless honours – CBE in 1974, knighted in 1979, Companion of the Order of Australia in 1998, Companion of Honour in 2003 – and his collection of medals rivalled that of any war hero; he also had a string of honorary degrees and awards. He was made President of Trinity College of Music in 2000, but he also accepted less glamorous honorary positions, knowing his name would benefit the organisations in question. He was, for example, a patron of Bampton Opera and the president of the Havergal Brian Society, having recorded Brian's Seventh and 32nd Symphonies for EMI in 1987.

In spite of the astonishing breadth of his repertoire, it was for his fidelity to the music of a handful of composers – and to the letter of their work – that Mackerras was most influential, hosing away the accretions of "performance practice" to reveal the score as initially intended. As a teenager, well ahead of the "early music" movement that later became fashionable, Mackerras recalled, "I made a point of reading studies of things like ornamentation and double-dotting rhythms in Baroque and Classical music." His encounter with Handel was a revelation:

"With the Fireworks Music, I saw the original orchestration and I thought 'My God, I wonder what this must sound like!' You know, the original has 24 oboes, and all those bassoons and horns... The opportunity came up in 1959 at the bicentenary of Handel's death, when we got every wind player in London to come for one session, in the middle of the night, and have a go at it."

His recordings of Handel oratorios and operas and of Janácek and Mozart operas were benchmarks, offering – usually for the first time – the music as the composer might have intended it in sharply defined, dramatically alert performances of considerable power.

The Mackerras discography is enormous, of course, and included a number of symphonic cycles: the complete Beethoven (for EMI and again for Hyperion, recorded live at the 2006 Edinburgh Festival with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra; "His tempi are wonderfully fleet," wrote one critic), Brahms and Mozart (both Telarc). In 1986 he reconstructed the Sullivan Cello Concerto, lost in a fire, from his memory of conducting it in 1953, and recorded it for EMI; he also committed a number of the Gilbert and Sullivan operettas to disc. Other operatic recordings include Donizetti, Dvorák, Gluck and Purcell.

His tireless attention to detail revealed itself also in matters of practical musicianship:

"I believe it's very important to edit orchestral parts explicitly and as thoroughly as possible, so that the musicians can play them without too much rehearsal. For instance, the other day I did all the Schumann symphonies with very little rehearsal at all. Because the parts were clearly marked, particularly with regard to dynamics, we were able to play them without needing to do that much preliminary work, focusing our attention on the interpretation rather than the technical business of who plays too loud or too soft."

Mackerras' Australianness extended to a forthright manner. His connections with Benjamin Britten, with whom he had worked since 1956, were abruptly severed when he joked about Britten's relationship with boys. Nor did he suffer fools gladly – this one once asked him if, given his long association with the music of Dvorák and Janacek, he had looked at any of the intervening Czech late Romantics, composers like Ostrcil and Jeremiáš; I was dismissed with a casual "Nah".

In spite of a lengthy battle with cancer, Mackerras continued to record and give concerts up to the end, his energy somehow overcoming his illness. Honorary president of the Edinburgh Festival since 2008, he was due to conduct Mozart's Idomeneo there on 20 August. Before that, he was scheduled to appear at the Proms on 25 July – a Viennese night – and a late-night concert of Mozart and Dvorák on 29 July. They would have been, amazingly, his 53rd and 54th appearances at the Proms. His first was in 1961 – and in 1980 he became the first non-Briton to conduct the BBC Symphony Orchestra on the Last Night. The concert on Sunday week will now be dedicated to his memory.

Martin Anderson

Alan Charles MacLaurin Mackerras, conductor: born Schenectady, New York 17 November 1925; married 1947 Helena Judith Wilkins (two daughters, one deceased); kt 1979; Medal of Merit, Czech Republic 1996; Companion of the Order of Australia 1997; Companion of Honour 2003; died London 14 July 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments