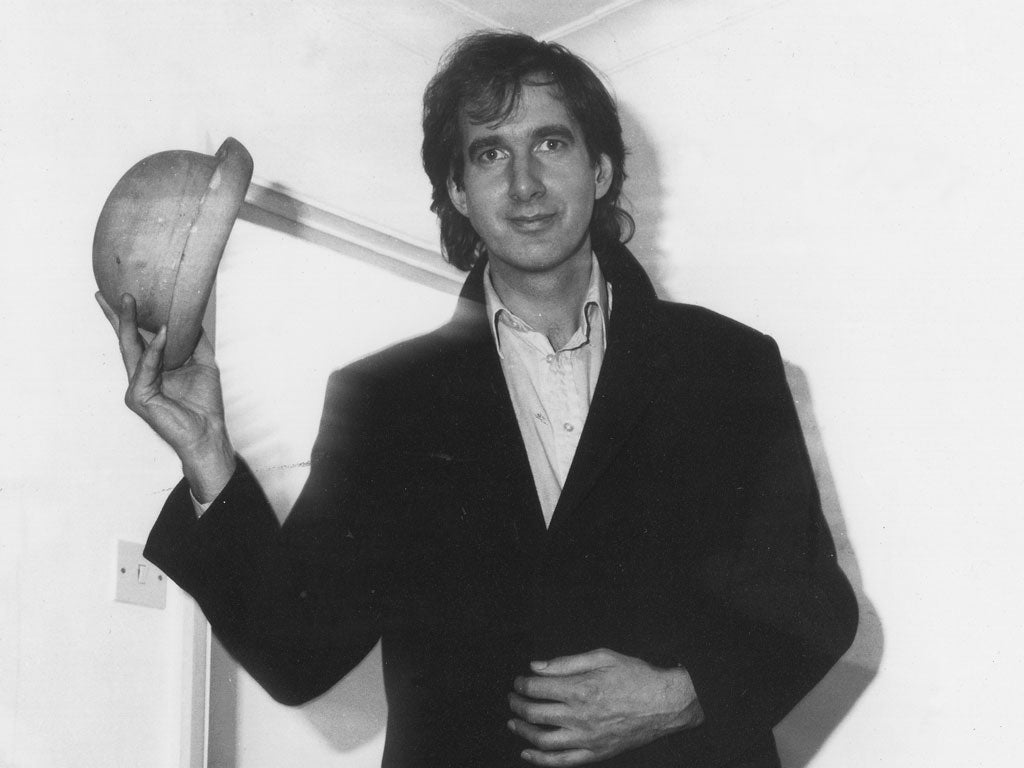

Simon Marsden: Photographer who struggled in his life and work against banal modernity

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Academics see in our undying fascination with the undead symptoms of political and economic unrest. Zombies, for instance, are an expression of guilt and dread regarding the lack of affordable care for the aged. The vampire is a vehicle for racial and geopolitical agendas. Ghosts, too, can be demystified, explained away in the light of historical and current events.

The intellectual project to reduce the timeless to the topical, and the irrational to the banal, is one Simon Marsden opposed both in practice andin principle. He was a romantic, engaged in mental war against modern technology, materialism and the prosaic in general.

Marsden was a photographer and master of darkroom techniques. He shot in black and white, often on infra-red film. His disdain for digital advances was inevitable given his commitment to the medium pioneered by Daguerre. The medium was part of the message, and photography for Marsden was partly a seance, an attempt at what Jonathan Swift called "real vision — the ability to see the invisible". In the camera and in the darkroom, light and photosensitive emulsion enacted a version of the alchemical wedding of spirit and matter. Marsden could wax poetic on the subject, but he was never po-faced about it. His ebullient laughter echoes in the memories of all who knew him.

As a boy, Marsden had been thrilled and terrified by the ghost stories his father read aloud to the family. That his boyhood homes were both dilapidated halls in the Lincolnshire Wolds added considerably to the effect these tales had on his imagination.

He began taking photographs as a young man partly to exorcise his own fears of the inhabited dark. Inspired by the Cottingley Fairies, the famous photographic hoax of the 1920s, Marsden's first photographs were of cardboard ghosts shot against real landscapes and houses. Subsequently he made it clear that he was not interested in trying to capture spirits on film; what haunted him was the atmosphere certain places had, the way certain sites seemed redolent of narratives untold.

Best known for his pictures of ruins, haunted houses, statuary and spectral landscapes (infrared film bleaches verdure white and darkens the sky) his photographs have been widely exhibited and are held in several collections worldwide. Aside from book jackets, his images were sought as album covers by rock bands of a Gothic tendency, most notably Cradle of Filth. In 1984, in a transaction marked by mutual respect, the band U2 paid Marsden compensation when it was pointed out that the cover of their album The Unforgettable Fire was a direct copy of the one on the cover of his first collection, In Ruins: The Once Great Houses of Ireland (with Duncan McLaren, 1980).

He went on to publish 12 more books of photographs, most of them accompanied by his own congenial texts. These include hallucinated photo-excavations of sites in France, Venice, East Germany and the US, as well as Ireland and the UK. A new book, Russia, A World Apart, with texts by Duncan McLaren, was in production when Marsden died and will be published later this year.

Marsden was on a lifelong quest, and he relished the adventures and encounters his travels afforded him, the more bizarre the better – the elderly brother and sister who welcomed him to Huntingdon Castle in County Carlow, for example, who regaled him over lunch with lore pertaining to the haunted history of their demesne and then posed for his lens in ceremonial robes in their very own Temple to Isis. Such natural hospitality and eccentricity inspired Marsden's romantic spirit and reinforced his sense of purpose. As he wrote in The Haunted Realm (1986), "I could only reflect that these were things to be protected in our modern day mechanical world."

Marsden could be scathing about the modern world and the values it seeks to impose. His critical tirades wereeloquent, heartfelt and often hilarious. He knew his quest was quixotic, that the invisible was no match against the forces of instant gratification,consumerism and junk culture. His cause was doomed, which may have been part of its appeal. He was in a long line of romantics and visionaries, stewards of lost causes, individuals whom he admired for their refusal or inability to conform.

Duncan McLaren relates that on their recent expedition to Russia Marsden found himself able to understand and to be understood by people on a level deeper than language. This won'tsurprise those who knew him. He was a wonderful communicator, able to broadcast and receive on many subtle wavelengths.

While his travels took him far afield, it was to the Lincolnshire Wolds that he returned when he married CassieStanton in 1984. They had a daughter, Skye, and a son, Tadg, and in a converted presbytery they set up a home for themselves and the Marsden photographic archive. Tadg now inherits the baronetcy created for Marsden's grandfather, owner of a Grimsby fishing fleet, in 1924. Cassie continues to oversee the Marsden Archive.

Peter Blegvad

Simon Neville Llewelyn Marsden, Bt, photographer: born Lincolnshire 1 December 1948; married 1970 Catherine Windsor-Lewis (divorced 1978), 1984 Caroline Stanton (one son, one daughter); died 22 January 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments