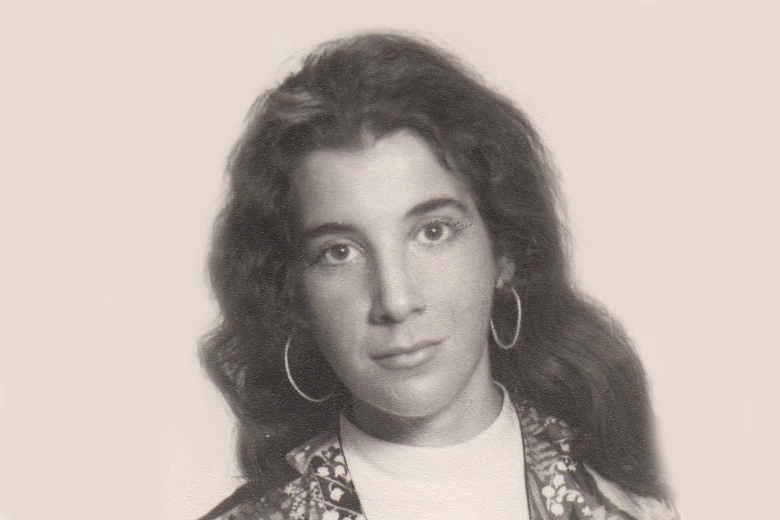

Sheila Michaels: feminist who brought the term 'Ms' back into common use

The prominent feminist changed the way modern women are addressed

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Half a century ago Sheila Michaels, who has died of acute leukaemia aged 78, helped to popularise the honorific “Ms”, thereby changing the way women could be addressed.

Michaels, who over the years worked as a civil-rights organiser, New York cabdriver, technical editor, oral historian and Japanese restaurateur, did not coin “Ms” nor did she ever claim to have done so.

But working quietly with little initial support from the women’s movement, she was midwife to the term, ushering it back into being after a decades-long slumber – a process she later described as “a timid eight-year crusade”.

“Apparently, it was in use in stenographic books for a while,” Michaels said in 2016. “I had never seen it before: It was kind of arcane knowledge.”

But for generations, “Ms” lay largely dormant.

Michaels first encountered the term in the early 1960s. She was living in Manhattan, sharing an apartment with another civil-rights worker, Mari Hamilton. One day, collecting the mail, she happened to glance at the address on Hamilton’s copy of News & Letters, a Marxist publication. It read: “Ms Mari Hamilton.”

Thinking the word was a typographical error, she showed it to Hamilton. No, Hamilton told her: It was no typo. The Marxists, at least, appeared to have had a handle on “Ms” and its historical meaning.

For Michaels, something in that odd honorific resonated. Growing up in St Louis, she had known women who were called “Miz” So-and-So – a respectful generic used traditionally there, as it also was in the American South.

“It was second nature to me,” she said in 2016, recalling the term’s familiar sound.

An ardent feminist, she had long dreamed of finding an honorific to fill a gap in the English lexicon: a term for women that, like “Mr”, did not trumpet its subject’s marital status.

Her motives were personal as well as political. Michaels held a rather dim view of marriage, she said, partly as a result of her mother’s experiences both in and out of wedded matrimony.

The daughter of Alma Weil Michaels, a writer for radio serials, Sheila Babs Michaels was born in St. Louis in 1939. She was given the surname of her mother’s husband, Bill Michaels, though he was not her father.

Her biological father was her mother’s lover, Ephraim London, a noted civil-liberties lawyer, whom Sheila did not meet until she was 14. When Sheila was still very young, her mother divorced Bill Michaels and married Harry Kessler, a metallurgist.

Harry Kessler did not want a child around, and so for five years, between the ages of about three and eight, Sheila was packed off to live with her maternal grandparents in New York. Later rejoining her mother and stepfather, she was known as Sheila Kessler.

After graduating from high school in St Louis, she enrolled in the College of William and Mary, in Williamsburg, Virginia. She was expelled in her sophomore year, partly, she said, for her anti-segregationist editorials as a member of the board of the campus newspaper.

In 1959, she moved to New York, where she went to work for the Congress of Racial Equality. In 1962, she worked with the organisation in Mississippi, where she also became involved with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

Named a field secretary for SNCC the next year, she worked in Tennessee as an editor of The Knoxville Crusader, a civil-rights newspaper. Her co-editor was Marion S Barry Jr, the future mayor of Washington.

Her civil-rights work did not sit well with her family. After she was arrested in Atlanta in 1963, they disowned her: Her stepfather had clients in the South. At their request, she forsook the name Kessler and became Sheila Michaels once more.

During these years, Michaels was seeking, as she told The Guardian in 2007, “a title for a woman who did not ‘belong’ to a man”.

“There was no place for me,” she continued. “No one wanted to claim me and I didn’t want to be owned. I didn’t belong to my father and I didn’t want to belong to a husband – someone who could tell me what to do. I had not seen very many marriages I’d want to emulate.”

On seeing the fateful mailing to her roommate that day in the early Sixties, she wondered whether those two incompatible consonants might solve her problem. “The whole idea came to me in a couple of hours. Tops,” she told The Guardian.

Surprising as it seems now, Michaels’s proposal met with little interest from other feminists. The modern women’s movement was then in embryo: Betty Friedan’s searing nonfiction book The Feminine Mystique, widely credited with having been its catalyst, would not appear until 1963.

In the early Sixties, many women on the front lines felt that there were bigger battles to be waged. Even Hamilton, whose newsletter had moved Michaels to action, was unpersuaded at first.

“She said, ‘Oh, Sheila, we have much more important things to do,'” Michaels recalled in 2016.

Then, in about 1969, Michaels appeared on the New York radio station WBAI as a member of the Feminists, a far-left women’s rights group.

During a quiet moment in the conversation, she brought up “Ms”.

“When the radio interviewer asked about the pronunciation,” she recalled in an interview in 2000, “I answered, ‘Miz'.”

Not long afterward, when Gloria Steinem was casting about for a name for the progressive women’s magazine she was helping to found, she was alerted to Michaels’s broadcast.

The magazine, titled Ms, made its debut in late 1971 as an insert in New York magazine; the first standalone issue appeared the next year. The honorific has since become ubiquitous throughout the English-speaking world.

A longtime resident of the Lower East Side of Manhattan, Michaels also had a home in St Louis. Her marriage to Hikaru Shiki, a chef with whom she ran a restaurant in Lower Manhattan in the 1980s, ended in divorce. (She was known during their marriage as Sheila Shiki y Michaels.)

The power of the term “Ms” was something she recognised almost from the start, as she told The Japan Times, an English-language newspaper, in 2000.

“Wonderful!” she recalled thinking, on learning the significance of the word on that curious address label. “'Ms.’ is me!”

Sheila Michaels, activist and feminist, born 8 May 1939, died 22 June

© New York TImes

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments