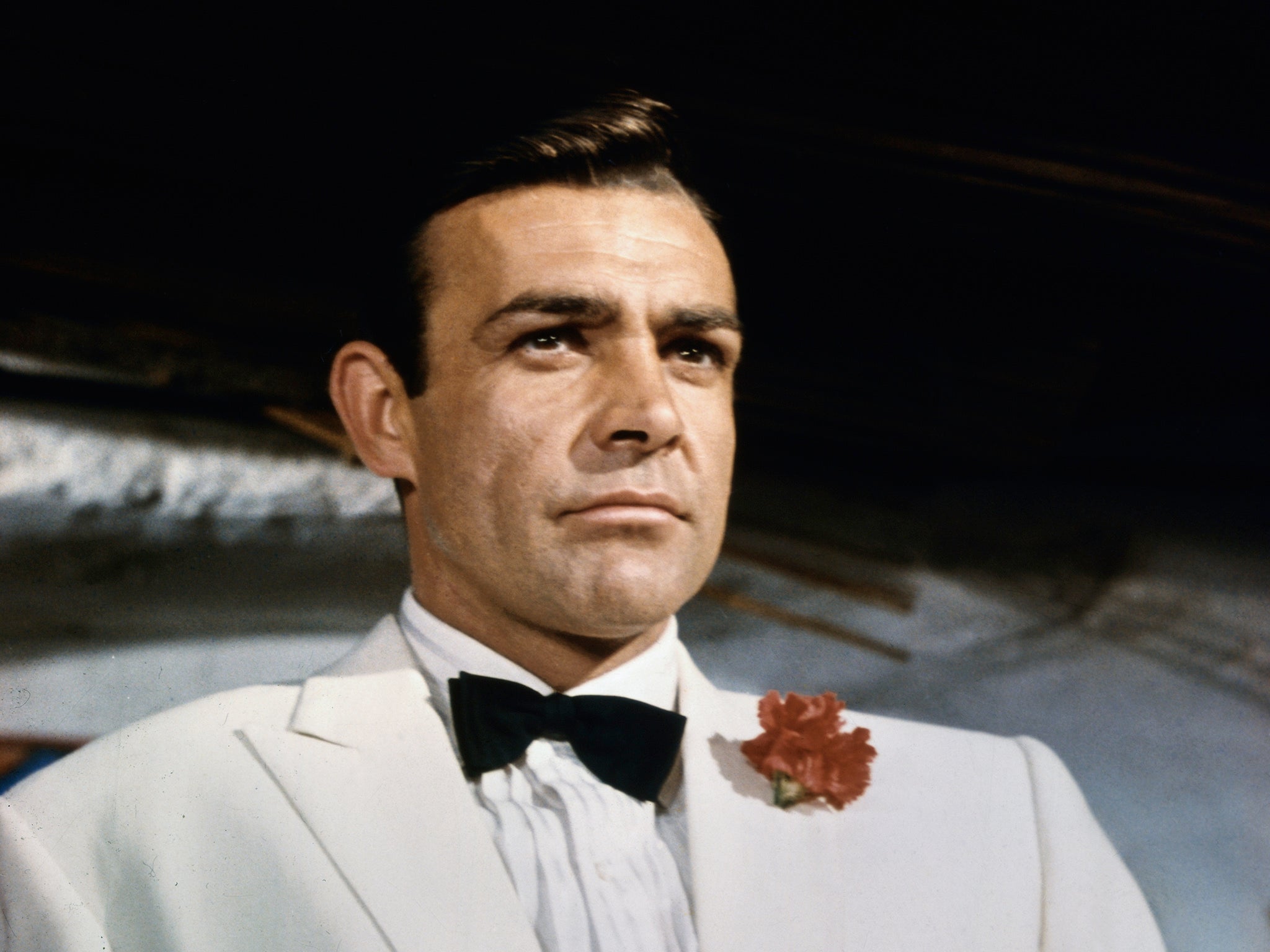

Sean Connery: Versatile actor who gave James Bond a licence to thrill

The role made him one of the iconic stars of the 20th century as he delivered 007’s lethal skills with a droll sense of humour

Sean Connery will always be associated with the role of James Bond, the cool, laconic hero of the Ian Fleming stories whom the actor recreated to perfection in Dr No and six other films that followed.

But he was also a versatile actor who never rested on his laurels and took many challenging and off-beat roles including his award-winning performances as a priest in The Name of the Rose and an ageing cop in The Untouchables. But audiences liked him best as the sartorially elegant secret agent with a “licence to kill”, a muscular connoisseur of women and wine, with lethal skills tempered with a droll sense of humour. “It was a bit of a joke around town that I was chosen for Bond,” he said in 1974. “The character is not really me at all.”

The product of a poor, working-class background, he was born Thomas Connery in an Edinburgh tenement in 1930, and he left school as a teenager to join the navy. Later jobs included milkman on a horse-drawn float, bricklayer, lifeguard and coffin polisher.

The late Alex Kitson, a former trade union official, who knew Connery in his youth, recalled, “He always had a smile and a joke for you. He had the height, the physique and, of course, if you lived in that part of Edinburgh you had to be able to handle yourself.”

It was Connery’s interest in body-building that first got him noticed, leading to his modelling boxer shorts and swimming trunks for advertisements on the pages of magazines including the popular film journal of the time, Films and Filming. In 1950, he represented Scotland in the Mr Universe contest, and the following year he made his stage debut when he joined the cast of the long-running musical South Pacific, at Drury Lane Theatre. Chosen to be one of the muscular young marines who sing “There Is Nothin’ Like a Dame”, he worked alongside Larry Hagman, the son of the show’s star, Mary Martin.

After taking advice that he should gain experience, he worked in repertory prior to making his screen debut with a bit part in the Herbert Wilcox production Lilacs in the Spring (1954). He followed this with small roles (usually as gangsters or low-lifes) in No Road Back (1956), Time Lock, Action of the Tiger and Hell Drivers (all 1957), but he had more rewarding roles on television, including Mat Burke in Anna Christie (1957) and John Proctor in The Crucible (1959), until he played a small, but important part in the Lana Turner vehicle Another Time, Another Place (1958).

Turner, whose company Lanturn was producing the film with Columbia, is alleged to have personally chosen Connery from the many actors who tested for the part of her lover. He figures prominently in the opening scenes as a married man having an affair in 1944 with fellow war correspondent Turner. After he is killed in a plane crash, Turner has a nervous breakdown, then, still obsessed with his memory, visits his home and befriends his wife and child without revealing her identity. The first film of Turner’s to be released after her part in the notorious stabbing of gangster Johnny Stompanato, the slow-moving, rather mundane, soap opera was thus accorded more attention than it deserved, but to the benefit of Connery, whom most critics agreed was one of the film’s few positive elements.

After a small role in Roy Baker’s superb account of the Titanic’s sinking, A Night to Remember (1958), and a featured role as one of five diamond scavengers making life difficult for the hero in John Guillermin’s Tarzan’s Greatest Adventure (1959) – considered one of the best of the non-Weissmuller Tarzans – Connery was given a starring role by Disney in Robert Stevenson’s Darby O’Gill and the Little People (1959), a delightful fantasy. In this whimsical tale of leprechauns and magic, he adopted an Irish accent, wooed Janet Munro, and even warbled a song.

In 1961, Connery played Alexander the Great in Rudolf Cartier’s BBC television production of Terence Rattigan’s play Adventure Story, and later the same year he was Count Vronsky to Claire Bloom’s Anna in a much-abridged (105 minutes) but effective version of Anna Karenina. On the cinema screen, he was third-billed as a hitman for gangster Herbert Lom in a tough and taut thriller, The Frightened City (1961), and he starred with Alfred Lynch in On the Fiddle, an engaging film about two soldiers who exploit the system for personal gain.

In 1962 he married his first wife, actor Diane Cilento, and in the same year, after a cameo role an all-star depiction of D-Day, The Longest Day (1962), he was cast in Dr No as James Bond, the role that would change his professional career. Ian Fleming, author of the James Bond adventures, confessed that when creating the character he always envisioned David Niven in the part of the debonair, martini-drinking ladies’ man, adept with lethal weapons, tuxedo-clad as he vanquished masterminds with dreams of world domination, and always ready with a quick-witted quip. Fleming made it clear he was unsure about the casting, and Connery later recalled, “He was a terrible snob, but a very entertaining man. I don’t think he approved of me terribly.”

The producers had complete confidence in their choice, advertising the film with the slogan, “Sean Connery is James Bond”, and audiences loved the insouciance and brio that Connery brought to the role, achieving a potent mix of virility, smooth sexuality and a tinge of self-mockery that his successors found difficulty matching. “It took some time to hit the right sort of humour,” he said, “but I look for humour in whatever I’m doing.”

Seen today, it is difficult to realise what a sensation the film caused, best summed up in the perceptive review by Richard Whitehall for the magazine Films and Filming. “Dr No is the headiest box-office concoction of sex and sadism ever brewed in a British studio, strictly bathtub hooch but a brutally potent intoxicant for all that. Dr No could be the breakthrough to something… but what? At one point Bond nonchalantly fires half a dozen shots into the back of an opponent – the British cinema will never be the same again.”

James Bond made Connery one of the iconic actors of the 20th century, but he was never entirely happy with the fame it brought him. “Nobody wants to be pigeon-holed to the extent that they only do this or only do that.”

He did, in fact, break away from the role to an extent that lesser actors would have found impossible, taking a wide variety of parts that certainly proved he was not a one-note actor. His choices were by no means safe projects. The first film to display his determination not to rest on his laurels was Sidney Lumet’s The Hill (1965), an uncompromisingly grim tale in which he played a military prisoner subject to harsh brutality in a British stockade. Martin Ritt’s The Molly McGuires (1970) was based on the factual secret organisation of anthracite miners who, in 1870s Pennsylvania, sabotaged mines and murdered bosses in protest at working conditions and unfair treatment. He worked with Lumet again (“a fine director who creates a team”) in another stark drama, The Offence (1973), playing an obsessive policeman determined to wear down a suspected child molester. Connery said, “It explores areas that people just don’t get to in films as a rule.”

One of his most controversial roles was that of an ageing Robin Hood opposite the Maid Marion of Audrey Hepburn in Richard Lester’s Robin and Marion. Too diffuse, actionless and morose for wide approval, it was one of the actor’s favourite roles, and he said of audience apathy, “They can’t take the idea that a hero might be over the hill and falling apart.”

Interspersed with such projects were the Bond films, their makers encouraged by the enormous success of Dr No to invest in increasingly elaborate set-pieces and astounding gadgetry. The second Bond adventure, From Russia With Love (1963), had memorable villains in Robert Shaw and particularly Lotte Lenya (whose shoes spout knives from their toes, with which she kicks opponents to death), and was not only superior to Dr No, but is considered one of the best of all the Bonds.

Goldfinger (1964) is a strong contender for the finest of all, with Shirley Bassey’s indelible performance of the title song behind the credits; an ambivalent heroine, Pussy Galore, who, as incarnated by Honor Blackman, is more than a match for Bond; the memorably exotic murder of Shirley Eaton’s character, who is suffocated when the pores of her skin are totally covered in gold paint; and two grand villains, Goldfinger himself (Gert Frobe), who intends to slice Bond in two with his laser ray gun, and his henchman (Harold Sakata), who sports a deadly razor-edged hat. (Goldfinger confirmed that the Bond films would be around for some time, taking more than three times the amount made by Dr No, and over twice that grossed by From Russia With Love.)

Between these films, Connery journeyed to Hollywood to act for Alfred Hitchcock in Marnie (1964), as a businessman who becomes infatuated with a thief (Tippi Hedren in a role that Hitchcock hoped would tempt Grace Kelly back to the screen).

It did not turn out to be one of Hitchcock’s finer works. He told Francois Truffaut that what attracted him to Winston Graham’s book was “the fetish idea”, adding, “A man wants to go to bed with a thief because she is a thief… Unfortunately, this concept doesn’t come across on the screen. To put it bluntly, we’d have had to have Sean Connery catching the girl robbing the safe and show that he felt like jumping at her and raping her on the spot.”

Hitchcock also made controversial comments about the casting: “I wasn’t convinced that Sean Connery was a Philadelphia gentleman. If you want to reduce Marnie to its lowest common denominator, it is the story of the prince and the beggar girl. In a story of this kind you need a real gentleman, a more elegant man than what we had.”

As Bond, who never lacked elegance, Connery continued to have huge box-office hits, with Thunderball (1965), a huge moneymaker but a lesser Bond, with much of the action taking place underwater, and You Only Live Twice (1967), promoted as the last Bond film to star Connery, while non-Bond films included Irvin Kershner’s A Fine Madness (1966), a quirky tale of a poet determined to write a masterpiece, and a sprawling western, Shalako (1968). The film offered the intriguing pairing of Connery with Brigitte Bardot, but the pair failed to strike sparks or bring life to the piece. To play the title character, whose name means “he who brings water”, Connery declined to play Bond again in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, which gave George Lazenby his chance to play 007.

Connery’s desire to quit Bond had provoked a stormy relationship with producer “Cubby” Broccoli, but after starring in Sidney Lumet’s caper movie, The Anderson Tapes (1971) in a role that Variety complained “lacks substance”, Connery accepted lucrative terms to return to Bond in Diamonds Are Forever (1971) after Lazenby’s effort received a generally negative response. Connery’s presence made Diamonds Are Forever a blockbuster, but James Brosman, in his book James Bond in the Cinema (1972), criticises the film’s over-complicated plot and its emphasis on laughs over thrills and suspense. Several critics also observed that Connery was getting older, and the actor announced that he would never again play the role.

His name on a marquee was considered such that when he accepted a role in Lumet’s all-star Agatha Christie mystery Murder on the Orient Express (1974), he was able to negotiate special financial terms whereas all the other cast members worked for a flat fee. His name was not enough to prevent tepid response to the sci-fi thriller Zardoz (1974), but John Milius’ The Wind and the Lion (1975) was a stirring, if jingoistic account of conflict between Teddy Roosevelt (Brian Keith) and an Arab chieftan (Connery) at the time when America was starting to become a world power.

Even better as high adventure was John Huston’s The Man Who Would Be King (1975), starring Connery with Michael Caine in a Rudyard Kipling tale of British imperialism that the director had been wanting to film for years – he once planned to have Clark Gable and Humphrey Bogart playing the leads.

Connery’s other roles included a cameo as Major General Urquhart in A Bridge Too Far (1977), based on the battle of Arnhem; a true-life role of the first man to rob a moving train in The Great Train Robbery (1979); and King Agamemnon, a mystical Greek warrior in Time Bandits (1981). Fred Zinnemann’s mountaineering tale Five Days One Summer (1982), lacked excitement, but cast member Anna Massey later stated, “Sean Connery was charming, and couldn’t have been more fun.”

In total, though, Connery’s films had not been too successful, and in 1983 he agreed to return to the role of Bond in the appropriately titled, Never Say Never Again. The result was pleasant enough, but failed to recapture the panache of the earlier movies. After starring in the popular fantasy Highlander (1986), he gave two of his most acclaimed performances. For his portrayal of a monk caught up in a murder mystery in The Name of the Rose (1986), he won a Bafta as Best Actor, and the following year he won an Oscar for his supporting performance as a grizzled Irish cop in The Untouchables (1987).

He then played the hero’s father to fine comic effect in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), and demonstrated that he could still play a romantic lead by convincingly wooing Michelle Pfeiffer in spy thriller The Russia House (1990) – in 1989 People magazine had voted him “the sexiest man alive”.

One of his last great films was the exciting thriller The Rock (1996), a finely paced and gripping action movie in which he was one of two men breaking into Alcatraz, being used as the base for a dastardly plot to inflict nerve gas on San Francisco. Having become an associate producer on several of his films in the Nineties, he was full producer on Entrapment (1999), co-starring Catherine Zeta-Jones.

He and Diane Cilento had a son in 1963, Jason Connery, an actor who played the creator of James Bond, Ian Fleming, in the television movie, Spymaker: The Secret Life of Ian Fleming (1990). After divorcing Cilento in 1973, Connery married French-Moroccan painter Micheline Roquebrune and established homes in Marbella (Spain) and the Bahamas.

His vocal support of the Scottish National Party (during his navy days he was tattooed with the words “Scotland Forever”, and later he donated nearly £4,800 a month to the party) and his hard campaign for a Yes vote during the Scottish referendum that created the Scottish parliament is alleged to have prompted Donald Dewar, then Scottish Secretary, to veto a knighthood in 1997. The actor went on to back Scottish independence in 2014.

Controversy was also stirred when it was reported that early in his career he said it was OK to slap a woman, and a knighthood was again denied in 1998. Connery was “deeply disappointed but strangely not angry or greatly surprised. Finally, in July 2000, the Queen travelled to Scotland to knight the actor, who was in full Scottish dress, including kilt. He said afterwards that “it was the proudest day of my life”. Champion racing driver Jackie Stewart, a close friend of Connery, said, “He has certainly earned it and he has been a great ambassador for Scotland and Great Britain.”

His last big-budget blockbuster, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, was released in 2003. He received the American Film Institute’s Lifetime Achievement Award and confirmed his retirement from acting in 2006.

In a lighthearted speech at the ceremony, he joked: “I’m more than pleased that you like my work. I have to admit it looked pretty damn good from where I was sitting.”

Striking a more serious tone, he continued: “It brought back to me lots of terrific memories. Memories of working with people who are fun and industrious, talented and enthusiastic. These are all the qualities that I find admirable.”

“The rest of you, well, you know who you are,” he added with a smile. “Making movies is either a utopia or it’s like shovelling s*** uphill.”

Sean Connery, actor, born 25 August 1930, died 31 October 2020

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks