Santiago Carrillo: Communist leader who assisted Spain's transition to democracy

After the death of Franco in 1975, Carrillo preached moderation and respect for the monarchy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

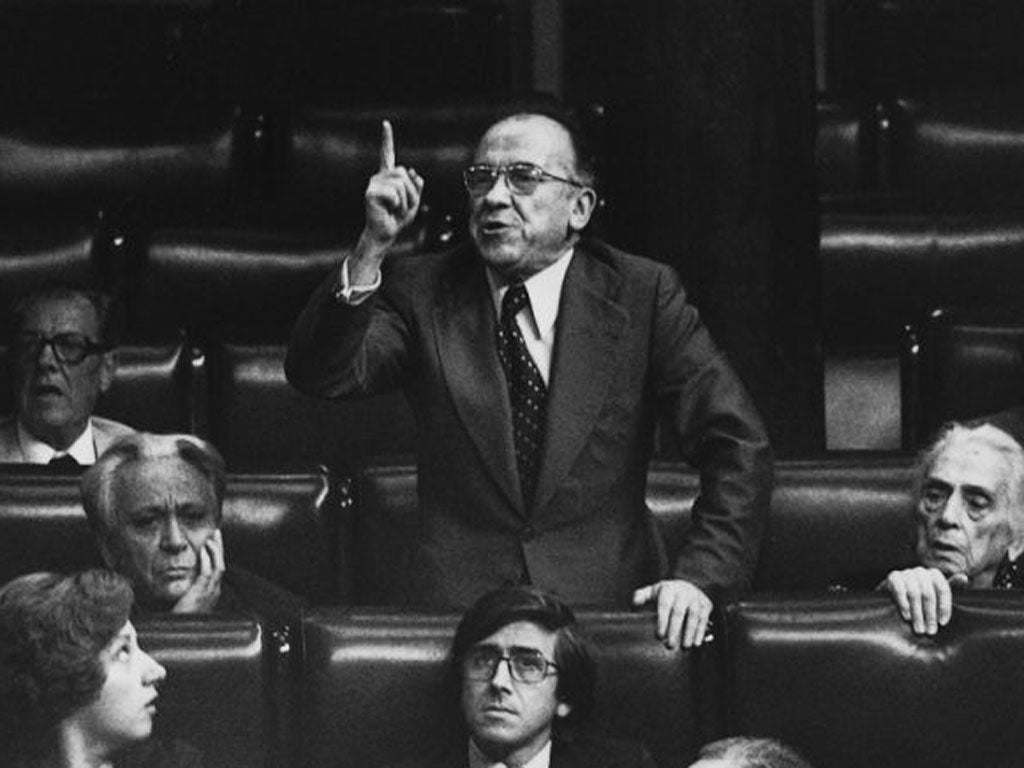

Your support makes all the difference.For many Spaniards, if there is one moment that summed up how important Santiago Carrillo's contribution was to their country's democracy, it came on the night of 23 February 1981, when around 200 Civil Guards plotting a coup d'état burst into the Spanish parliament brandishing sub-machine guns and ordered MPs to lie on the ground. Three refused, even when one Civil Guard fired off a warning round – the acting President Adolfo Suárez, his Minister of Defence, General Gutierrez Mellado, and Carrillo, the Communist Party leader.

"When they [the Civil Guards] then took me outside I thought they were going to shoot me," Carrillo later recalled. "But I thought the important thing was that I should behave in a dignified way so that the scoundrels could not laugh at me and what I represented."

Together with Suárez and Gutierrez Mellado, Carrillo's passive but effective resistance that evening provided a crucial sign to his fellow Spaniards that at least part of its political classes would stand up to any attempts, at gunpoint or otherwise, to reinstate a Franco-style military dictatorship. And as King Juan Carlos said after visiting Carrillo's family to pay his condolences only two hours after his death, at 97, the Communist leader was "a fundamental person for democracy" – almost certainly a reference to the key role played by Carrillo, as head of the Communist Party until 1982, in the period of political transition and reconciliation following the death of General Franco.

Yet Carrillo's importance in Spanish politics stretches back even before Franco took power. As a teenage secretary-general of the Spanish Socialist Party's youth movement he helped forge the plans for the working class uprising in Asturias against the Republic's right-wing government in 1934 – viewed by some as the earliest battle of the Civil War that was to rip Spain apart from 1936 to 1939. He was then instrumental in the fusion of the Socialist and Communist youth movements in April 1936 – to the latter's considerable advantage, and which helped tipped the balance of Republican power in the Communists' favour during the Civil War.

Carrillo's next major role was in the War itself, where at 21, he became a public order official on the defence committee hastily formed for Madrid in the autumn of 1936 as Franco's troops approached the capital and the Republican government decamped to Valencia. While he claimed that he had no part to play in a subsequent massacre of around 2,000 Nationalist prisoners that were technically under his supervision, Carrillo remains accused of having helped organise the evacuation of the prisoners from a Madrid jail that led to the greatest single war crime committed on the Republican side during the Civil War.

After a spell in Moscow following the Republic's defeat in 1939, Carrillo continued to work his way rapidly up the Spanish Communist Party (PCE) hierarchy, first leading the exiled party in France, then becoming its secretary general in late 1959. Through the 1960s, as the PCE spearheaded a broader anti-Franco resistance movement, Carrillo gradually distanced himself from his former Russian allies. His condemnation of the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 was one of the first key actions by the new political tendency of Eurocommunism, which saw several western European Communist parties pull themselves out of Moscow's orbit.

After Franco's death in November 1975, the PCE remained outlawed; hence Carrillo's return to Spain was a clandestine one, and the need to resolve its legal status became one of the most important components of the transition. An appearance at a press conference in late 1976 which led to his brief arrest all but ensured that the government had to tackle the question of the PCE's legalisation, which duly took place the following April.

From that point on, with Carrillo preaching moderation and recognition of the monarchy, and with regular contacts between himself and President Adolfo Suarez, the Communists could no longer be depicted as the bogeymen of Spanish politics, an image which Franco had manufactured to help maintain his hold on power. Instead they were seen as willing participants in the transition towards democracy.

However, that participation came at a high price, for Carrillo and his party. The PCE lost out badly to the Socialists in Spain's first democratic elections, in 1977 and again in 1982, with four deputies elected compared with 202 for the Socialists; Carrillo's resignation as general secretary was almost inevitable. In 1985, following a power struggle, he was expelled from the party. He remained an acerbic and astute political observer and writer to the end of his life. His place in the pantheon of Spain's political giants is secure.

Santiago Carrillo: politician: born Gijon, Spain 18 January 1915; married Chon (divorced 1944; one daughter deceased), 1949 Carmen Menendez (three sons); died Madrid 19 September 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments