Rubin 'Hurricane' Carter obituary: Boxer whose unjust murder conviction became a cause célèbre and who then worked for others wrongly imprisoned

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Long before the fame, the Bob Dylan song, the film, the savage manipulation of truth and the violent nights in the ring Rubin Hurricane Carter looked destined for a grisly end. "I was isolated long before they put the handles on me, before the boxing, before the murders: I was marked," he told me one night in 1997.

In 1966 Carter was stopped by police in Paterson, New Jersey, after four people had been shot in a bar. Two died instantly, one died a month later and Carter and the young man in the car with him at the time, John Artis, were eventually arrested and charged with the three murders. They both insisted that they were innocent men; the evidence against them was provided by two known criminals, eye-witnesses on the night who were in the vicinity planning their own robbery.

Carter narrowly missed the death penalty in 1967 at the first trial and was given three life sentences for the brutal slayings. "They wanted the electric chair. The amazing thing is that the white jury came back with guilty with a recommendation for mercy. If they just for one second believed that I killed those people they would have burnt me to death."

Carter had been a troubled boy growing up in Paterson; sent to a youth detention centre at 11 and escaping at 17, and he was on the run when he joined the US army. He served in Germany but was discharged and sentenced to 10 months for still being on the run. He became a street thug and was sentenced to four years for assault and snatching a purse. He was released in 1961 and instantly became a professional boxer. That is the story of the Hurricane.

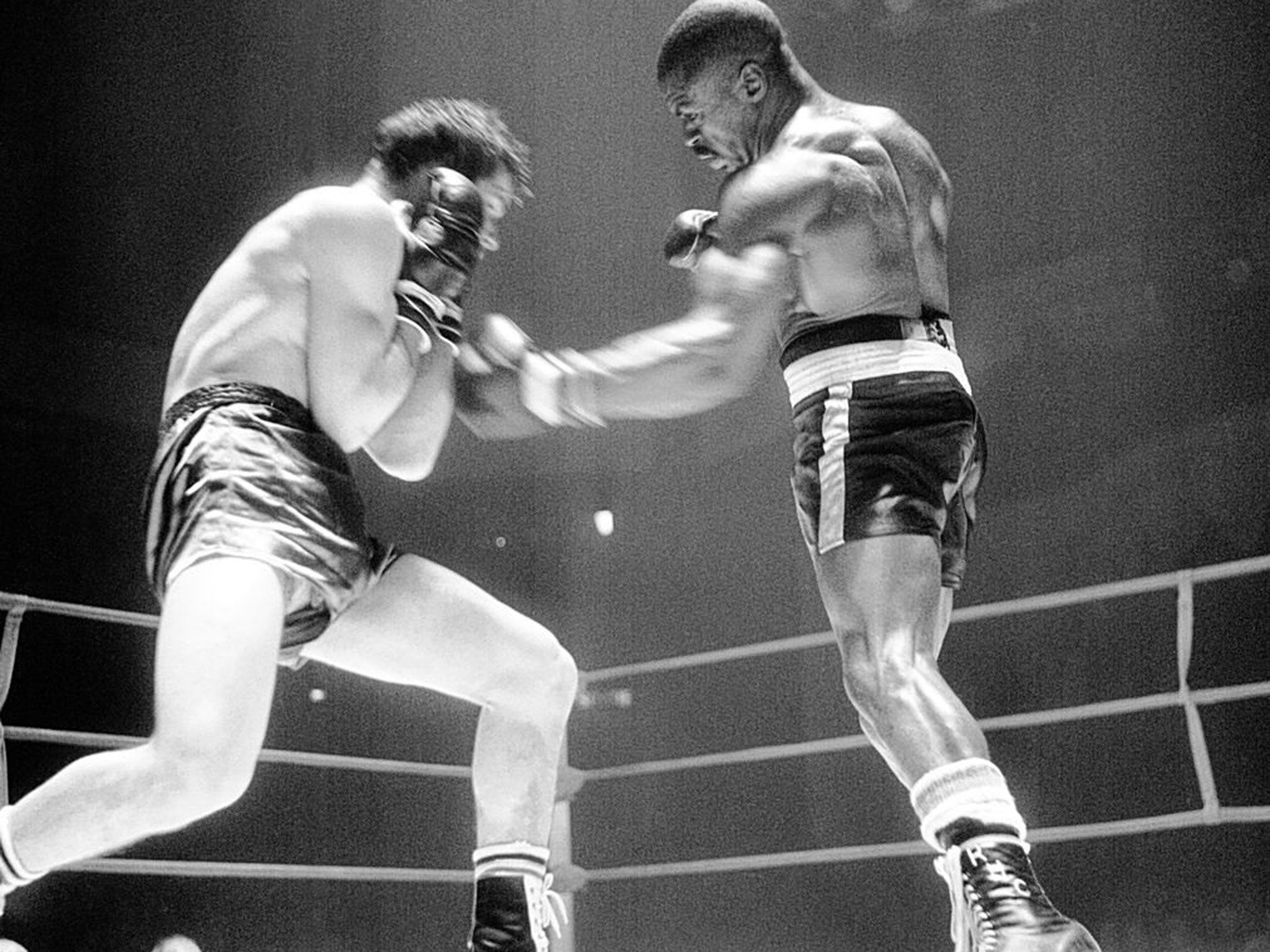

It is Carter's boxing career that sets up the notoriety of his outrageous incarceration and, a closer look at his boxing credentials exposes a few of the myths surrounding his eventual freedom. In the ring he was exciting, formidable at times and promotional candy with his shaved head, malevolence and growing militancy.

In 1963 he beat Emile Griffith, dropping the world welterweight champion three times for a first-round stoppage, and in his next fight, in early 1964, he was too good for Jimmy Ellis; four years later Ellis would fill the gap created by Muhammad Ali's forced exile and become the heavyweight champion of the world. Make no mistake, Carter could fight.

In 1964 he fought for the middleweight championship of the world against the Italian-American outcast Joey Giardello, who had had to wait until he had fought 125 times before boxing for the title. Giardello beat Carter easily on the night in his home town of Philadelphia; he also later collected an undisclosed sum after filing a lawsuit claiming defamation when the 1999 film, The Hurricane (which starred Denzel Washington in the title role), took scandalous liberties with its depiction of his victory. "The bums made me look like a racist bum," said Giardello, whose love affair with the fridge dominated his long career.

After losing the Giardello fight, Carter fought 15 more times, winning seven, and was still a contender before the night of the murders, but he was certainly not the leading middleweight contender. Two months before the shootings, Carter's old opponent, Griffith, beat Dick Tiger, who had beaten Giardello, for the world middleweight title; there is a very real chance that Carter would have been given another world title fight.

Carter was sentenced in June 1967, and from the start he was not an easy prisoner. He was in solitary confinement because of his refusal to accept his sentence and became known as "The Lord", a legend to other prisoners with the status to match his name.

The injustice of his prison term attracted attention: Dylan wrote "Hurricane" with Jacques Levy in 1975 – it appeared on his album Desire the following year – and there was a benefit concert at Madison Square Garden. Carter had written his book, The Sixteenth Round, in 1974 and eventually both he and Artis were released in March 1976. Ali picked Carter up at the prison gates, drove him to New York and handed over as much as $5,000.

However, a retrial later that same year ended with the pair back behind bars. Artis was released in 1981 and Carter set free in November 1985, after serving 19 years for the triple murder. There was no pardon or compensation, but in February 1988 a judge in New Jersey formally dismissed the indictments against the former boxer. Carter left for Toronto shortly after and lived there until his death.

"I had to get free and win that 16th round," Carter told me at his home in 1997. "I had to get clear of the iron bars and the stone walls. I had to do that for all the people that campaigned for me over the years." As a free man Carter devoted his time to freeing other innocent men, first with the Association of Defence of the Wrongfully Convicted and then with Innocence International Inc.

In many ways there was never going to be a fairy-tale ending to the Hurricane's story – three marriages, two children and a lot of hate – and his relationship with people he had loved and who had helped him often ended in bitter acrimony. Carter was a difficult man.

In the end it was Artis, the "other guy" on that night in June 1966 when the shots rang out, who returned to Carter's side, loyal and devoted after nearly 50 years. Artis was offered freedom if he implicated Carter and had refused each time. It was Artis who nursed his great friend through prostate cancer to the very end.

Rubin Carter, boxer and prison activist: born Clifton, New Jersey 6 May 1937; married three times (one daughter, one son); died Toronto 20 April 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments