The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

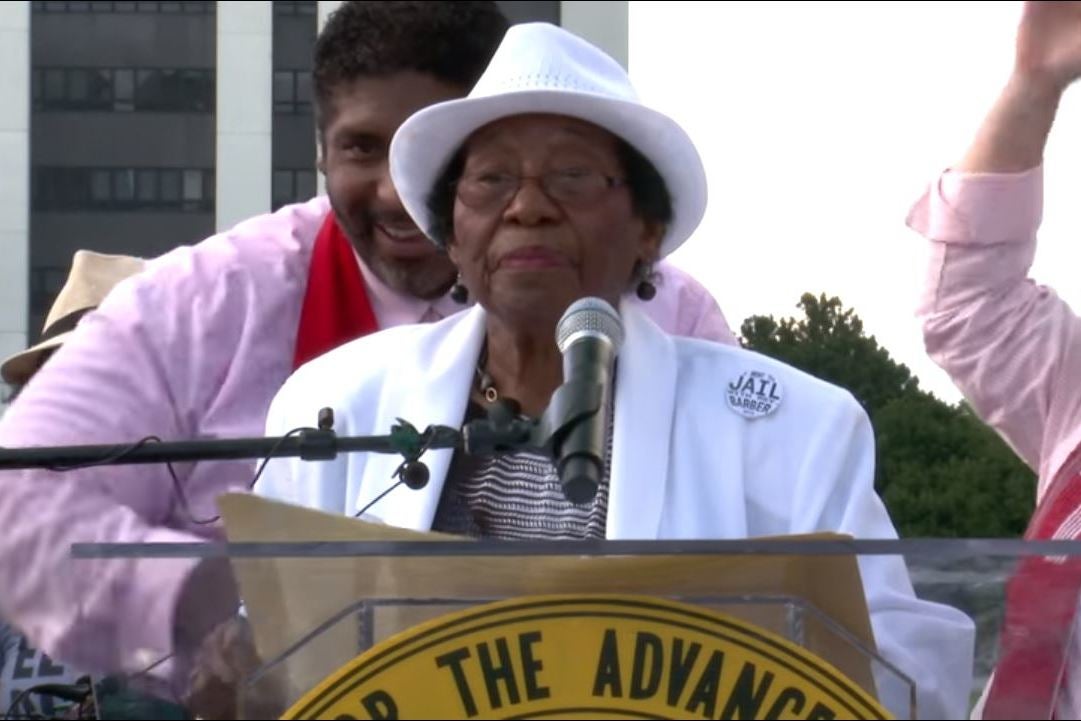

Rosanell Eaton: Civil rights activist praised by Obama as an unsung hero

A witness to Jim Crow-era racism, in her nineties she successfully campaigned against a law disenfranchising black people in North Carolina

When she first registered to vote in 1942, Rosanell Eaton rode a mule-drawn wagon to the county courthouse in North Carolina where she was greeted by three white men. “What do you want, little girl?” one of them asked Eaton, who was 21 years old.

Upon hearing what business had brought her to the courthouse, one of the men instructed her to recite the preamble to the US constitution. The challenge was a form of the literacy tests cynically used during America’s Jim Crow era to prevent African Americans from voting.

To the officials’ surprise, Eaton flawlessly recited the text, with its promises of forming “a more perfect union,” establishing justice and securing “the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity”.

“You did a mighty good job,” one of the men told Eaton, according to an account published in 2016 in The Atlantic. “Well, I reckon I have to have you to sign these papers.”

That test was only the first of the injustices Eaton would endure. It was also one of her first triumphs at the ballot box as a little-known but unyielding advocate of voting rights.

Eaton, who has died aged 97, came to prominence as late as 2016, as a lead plaintiff in a North Carolina lawsuit that defeated draconian voter ID legislation at the supreme court. Many civil-rights activists had described it as a modern-day effort to disenfranchise blacks and other minority voters with discriminatory practices at the polls. Amid her legal struggle, she was celebrated by President Barack Obama as an “unsung” American hero.

Eaton, a former teacher who by her count had helped register 4,000 people to vote, witnessed crosses burned in her yard during her years as an activist. She joined the North Carolina lawsuit in 2013 in protest against a state law that, among other provisions, required prospective voters to present photo identification, barred them from registering the same day that they intended to vote, and shortened the early voting period. The measure came on the heels of a supreme court decision substantially weakening the Voting Rights Acts of 1965.

North Carolina governor Pat McCrory, a Republican, remarked that “common practices like boarding an airplane and purchasing Sudafed” required photo identification and said that voting regulations should be no less stringent. Opponents of the measure responded that evidence of voter fraud was scant at best. They described the legislation as one of the most restrictive voting measures in the country and argued that it would have the effect of obstructing African Americans from voting.

For Eaton, the law created a bureaucratic tangle that she said forced her to make 10 trips to America's equivalent of the DVLA and drive more than 200 miles to various government offices to sort out a discrepancy on her driver’s licence. Her driving licence used her married name, while her voter registration card used her maiden and married names. She also found that her social security card had an incorrect birth year.

“It was maybe harder for me to get to vote after the law than it was all the way back then,” Eaton told The Atlantic.

After an initial legal defeat for the lawsuit, a federal appeals court struck down the law in 2016, recalling “the inextricable link between race and politics in North Carolina” and condemning the law for targeting “African Americans with almost surgical precision”.

Explaining its decision, the court noted that, after requesting data on forms of identification used by voters in the state, legislators had disallowed those types used most frequently by blacks. A 4:4 ruling by the supreme court the same year allowed the decision to stand. In 2017, after the seating of Justice Neil Gorsuch, the high court declined to hear another appeal.

“It’s a cruel irony that the words that set our democracy in motion were used as part of the so-called literacy test designed to deny Rosanell and so many other African-Americans the right to vote,” Obama, the first African American US president, wrote in a letter to the New York Times in 2015, responding to a magazine article that mentioned Eaton as it chronicled efforts to subvert the Voting Rights Act.

“Yet more than 70 years ago, as she defiantly delivered the Preamble to our Constitution, Rosanell also reaffirmed its fundamental truth,” he continued. “What makes our country great is not that we are perfect, but that with time, courage and effort, we can become more perfect. What makes America special is our capacity to change.”

Rosanell Johnson, a granddaughter of slaves and the youngest of seven children, was born on a farm outside Louisburg. After her father died when she was two, Eaton’s mother became a sharecropper.

In the early years of her life, Eaton farmed for a living. She later did packing work at a plant before taking university classes to become an educator. She worked a phonics teacher and a librarian assistant before retiring at 70. She then became a substitute teacher and tutored children at her home into her eighties, according to her daughter.

Her husband, Golden Eaton, died in 1963. Their son James Eaton died in infancy. Their daughter Annie Montague died in 2000, and their son Jesse Eaton died in 2004.

Besides her daughter Armenta, Eaton is survived by four grandchildren and nine great-grandchildren.

Eaton, who had also volunteered for years as a polling clerk, was once asked why she devoted so much time to registering others to vote and ensuring that she, too, could cast her ballot. “I think,” she said, “it is because my foreparents or forefathers didn’t have the opportunity.”

Rosanell Eaton, civil rights activist, born 14 April 1921, died 8 December 2018

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks