Ronnie O'Byrne: Stalwart of the Amalgamated Engineering Union

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

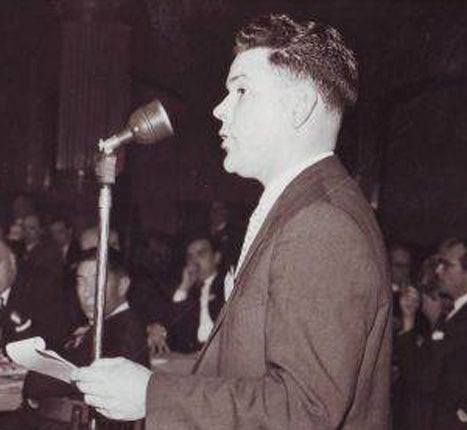

Your support makes all the difference.In the 1960s and '70s, ICI was a considerable power in the land, and their main Board was one of the major centres of power in Britain. Since the culture of the company was to have sensible industrial relations conducted on a basis of dignity, ICI established a suitable mechanism, the ICI Central Committee, representing all relevant trade unions. Primus inter pares was the Amalgamated Engineering Union, and for more than 20 years one of its members, a protégé of the AEU's powerful General Secretary, the Salvation Army officer John Boyd, was his Roman Catholic and fellow Scot, Ronnie O'Byrne.

O'Byrne certainly made an impression at ICI. Sir Paul Chambers, chairman from 1960-68, said to me, "Do you know the Scot Ronald O'Byrne?"

"Certainly," I responded. "He lives within two miles of me."

"Well, I would willingly have had him proverbially shot. Why? Because he squeezed out of us a pension scheme for ICI employees which will cost us a lot of money. But Mr O'Byrne is a very talented negotiator, and I like the guy."

In retrospect, the ICI pension scheme was a model of enlightened public relations, and a significant part of its enduring success was due to O'Byrne's assiduous work on the Central Committee. Another Scot, Sir Gavin Laird, General Secretary of the AEU and later a Member of the Court of the Bank of England, told me he thought O'Byrne was an effective and responsible colleague in the Union.

Ronnie O'Byrne was born in Bathgate to a family which had been connected with the coal and shale oil industries. After a good grounding at St Mary's Secondary School in Bathgate, where a caring and formidable headmaster, Dr John McCabe, made sure that his pupils were properly equipped in the basics, O'Byrne was called up in 1944, his natural athleticism directing him to the Army Physical Training Corps. Such were his leadership qualities that he became a sergeant before his 19th birthday. Moreover, he won the Inter-Service national light-middleweight boxing title in 1947. He would often reflect that he was due to fight a young unknown representing the Navy by the name of Randolph Turpin. Alas, Turpin was called away and the fight did not take place, to O'Byrne's sadness because he had anticipated victory.

After a short period in the shipyard at Grangemouth, O'Byrne spent the next 29 years as a process worker at ICI's Dyestuffs Division in the town. As a shop steward his philosophy was that you must always keep negotiating and never walk out, or away from trouble.

He became chairman of West Lothian Labour Party, which at the time of devolution in the 1970s embraced a significant number of deeply committed and argumentative members both for and against the Labour government's plans for an Assembly in Edinburgh. He handled differences with skill. He himself opposed devolution, basically on the grounds that the Trade Union movement should not be fragmented by differences between England and Scotland. His experiences at ICI's headquarters at Millbank in London taught him that the interests of workers in Scotland and England were not different.

He was one of the first to see that an Assembly or Parliament in Edinburgh, once set up, would never be satisfied until the situation became indistinguishable from a separate Scottish state. As Constituency Labour Party chairman, he tore up and threw into the wastepaper basket a letter from Transport House in 1978 suggesting that, as the arch anti-devolution MP, I should be deselected. "We'll deal with Tam Dalyell as we think necessary," he told them. "He is our responsibility not yours."

Ron Hayward, General Secretary of the Labour Party, told me that the 20,000+ Labour majority in West Lothian had made a nonsense of their warnings that my reckless opposition to a Scottish Assembly would lose the seat. That the result was so satisfactory for the Labour Vote No Campaign was in part due to O'Byrne's vigorous and forthright support.

He became a West Lothian councillor, for Winchburgh, and Alex Linkston CBE, who was later the Council's Chief Executive when it was the UK Council of the Year in 2006, was a junior employee of the Council on the fast track and saw O'Byrne at close quarters.

"He was the first of the modernisers," Linkston told me. "He was prepared to challenge senior councillors as to whether they were really obtaining value for money from well-established contractors and architectural partnerships with whom they had cosy relationships. We council officials were excited by a brave politician who was prepared to put his head above the parapet."

One particular action of O'Byrne's, revealing his political courage, enthralled me for months as the local MP. A devout Roman Catholic, married to a devout and formidable wife, he was prepared as chairman of the Education Committee to take on the Archbishop of St Andrew's and Edinburgh, Cardinal Gordon Gray, a galaxy of monsignors on Education Committees, and the Catholic hierarchy in Scotland. They were jealous in protecting the terms of the hard-won 1918 Education Act in Scotland, which guaranteed separate Catholic schools. O'Byrne was determined to save money and resources by setting up two new primary schools, one Protestant, one Catholic, side by side and sharing facilities like heating, catering and sports. My erstwhile Winchburgh constituents, then 10 years old and now in their 50s and 60s, tell me that O'Byrne was justified.

No Labour activist was more concerned about the situation in Northern Ireland and feared that it could be repeated in some parts of Scotland in the 1960s and '70s. It was typical of O'Byrne that he should seek constructive and practical solutions to resolve difficult situations.

Tam Dalyell

Ronald O'Byrne, trade unionist and ICI process worker: born Bathgate 24 April 1926; Army Physical Training Corps, 1944-48; process worker, ICI Dyestuffs Division, 1949-78; married 1954 Bridget McWilliams (one son, one daughter); died Livingston 12 January 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments