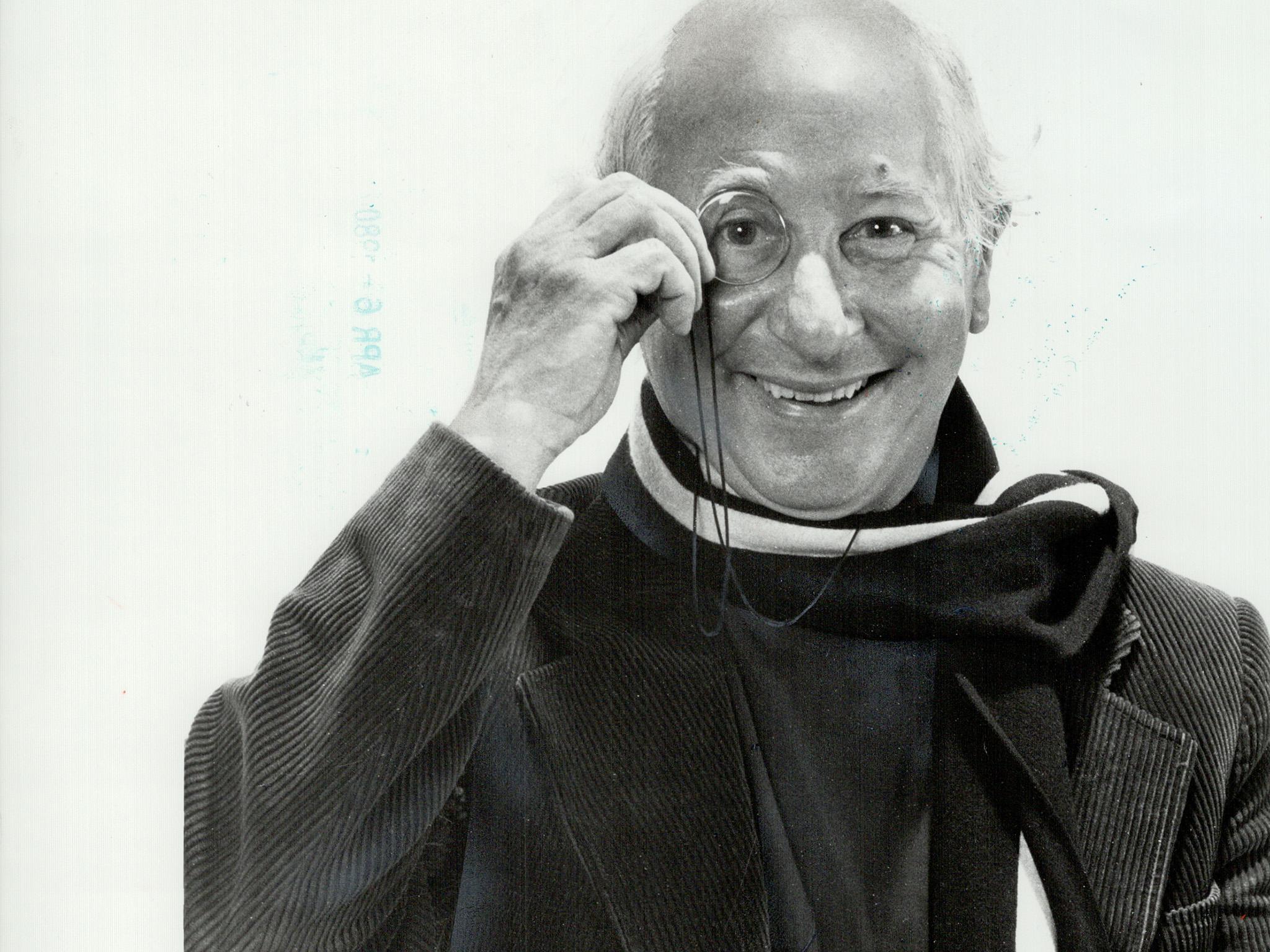

Richard Gordon obituary, doctor and author

The creator of the blockbusting ‘Doctor’ series learned to write as the BMJ’s obituaries editor

Richard Gordon, the anaesthesiologist who left the medical profession for a five-decade career as a writer – mining his memories of arrogant surgeons and hard-drinking doctors to comic effect in the popular 1952 novel Doctor in the House and more than a dozen sequels – died on 11 August. He was 95.

In fact, “Richard Gordon” was a pen name for Dr Gordon Stanley Ostlere, who wrote more than 30 books. They included fictionalised accounts of the nurse Florence Nightingale – he described her as a lesbian whose “experience of women is almost as large as Europe” – and Jack the Ripper, whose eviscerations he detailed with surgical precision.

While nearly all his novels drew upon his short-lived medical career, his work was concerned less with the art of diagnosis than with the fickle, fragile nature of human beings. “Being a doctor, for Gordon, is a framework in which to write about humanity, and jokes are a way of dissecting truths about failure, death, ignorance and venality,” the critic Michael Bywater wrote in 2008.

After studying medicine at Cambridge, Gordon was professionally adrift – working as a surgeon on a cargo ship in the South Pacific – when he began writing his first book in 1950. “I had nothing to do except drink gin with the chief engineer,” he later told the Daily Mail. “To save myself from developing cirrhosis of the liver, I wrote about my experiences as a medical student.”

The result was Doctor in the House, a ribald comedy about a callow, rugby-playing medical student who chases women, spends nearly as much time at the bar as at the hospital and is eventually “transformed from an un-earning and potentially dishonest ragamuffin to a respectable and solvent member of a learned profession.” The protagonist, like the pseudonymous author, was named Richard Gordon.

The novel sold more than three million copies and was reportedly used to teach conversational English in Japan. Two years later, it was adapted into a popular film starring Dirk Bogarde – his character’s name was changed to Simon Sparrow – alongside a trio of rowdy medical students played by Donald Sinden, Kenneth More, and Donald Houston.

While the film helped cement Bogarde’s popularity, its most memorable role was filled by James Robertson Justice, who played the booming, bearded chief surgeon Sir Lancelot Spratt. The character, who urged his charges to know “the bleeding time,” was in part a reflection of Gordon’s dislike for surgeons – a class of people so egotistical and deprived, he said, that they were “a damn sight worse than patients.”

Gordon helped write the movie’s script and contributed to its sequel, Doctor at Sea (1955), which featured Brigitte Bardot in her first major English-language role. The film was followed by five more movies and a string of theatre, radio and television adaptations in the Sixties and Seventies, many of them created with the author’s collaboration.

While Gordon’s writing persona was often that of a worldly charmer, he said he suffered from an “anxiety neurosis” and disliked meeting people – which led him to become an anaesthesiologist. As one of his characters put it in Doctor at Large (1955), the field placed patients in one of three stages: “awake, asleep and dead.”

Gordon attempted to help other doctors avoid that last stage in one of his first books, Anaesthetics for Medical Students (1949). The textbook was written, he said, so that students could turn to the index to find entries such as “Patient: going blue, what to do.” He married Mary Patten, a fellow anaesthesiologist, in 1951. According to some accounts, he proposed to her while they were standing over an unconscious patient. He is survived by Mary and their four children.

Gordon traced his writing career back to a childhood love of PG Wodehouse and to a stint at the British Medical Journal in the late 1940s. He often joked that he “learned to write convincing fiction” while running the journal’s obituaries section.

By the mid-1960s, he said he “felt due for a literary change of life” and turned to writing more serious novels such as The Facemaker (1967), about an ambitious plastic surgeon in 1918, and The Facts of Life (1969), about a female physician who wages a legal battle against a corporate drug manufacturer. However, his sense of humour never entirely left him. He was a prolific contributor to Punch magazine, and also edited such books as The Literary Companion to Medicine, an acclaimed 1993 anthology that offered puckish descriptions of James Boswell’s 19 bouts of gonorrhoea and Charles Dickens’s bloody bowel movements.

“Medicine means life and death, deliverance and despair, hope and fright, mystery and mechanics,” Gordon wrote in the book’s introduction, offering an explanation for the continuing popularity of medical books and novels. “It is a microscope trained upon life’s fundamentals, eagerly focused by novelists since the 1820s. Readership is guaranteed. There may be doubters about the soul, but no one can deny the existence of the body, and everyone wants to know the terrible things that can happen to it.”

Richard Gordon (Gordon Stanley Ostlere), doctor and writer: born 15 September 1921; died 11 August 2017

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks