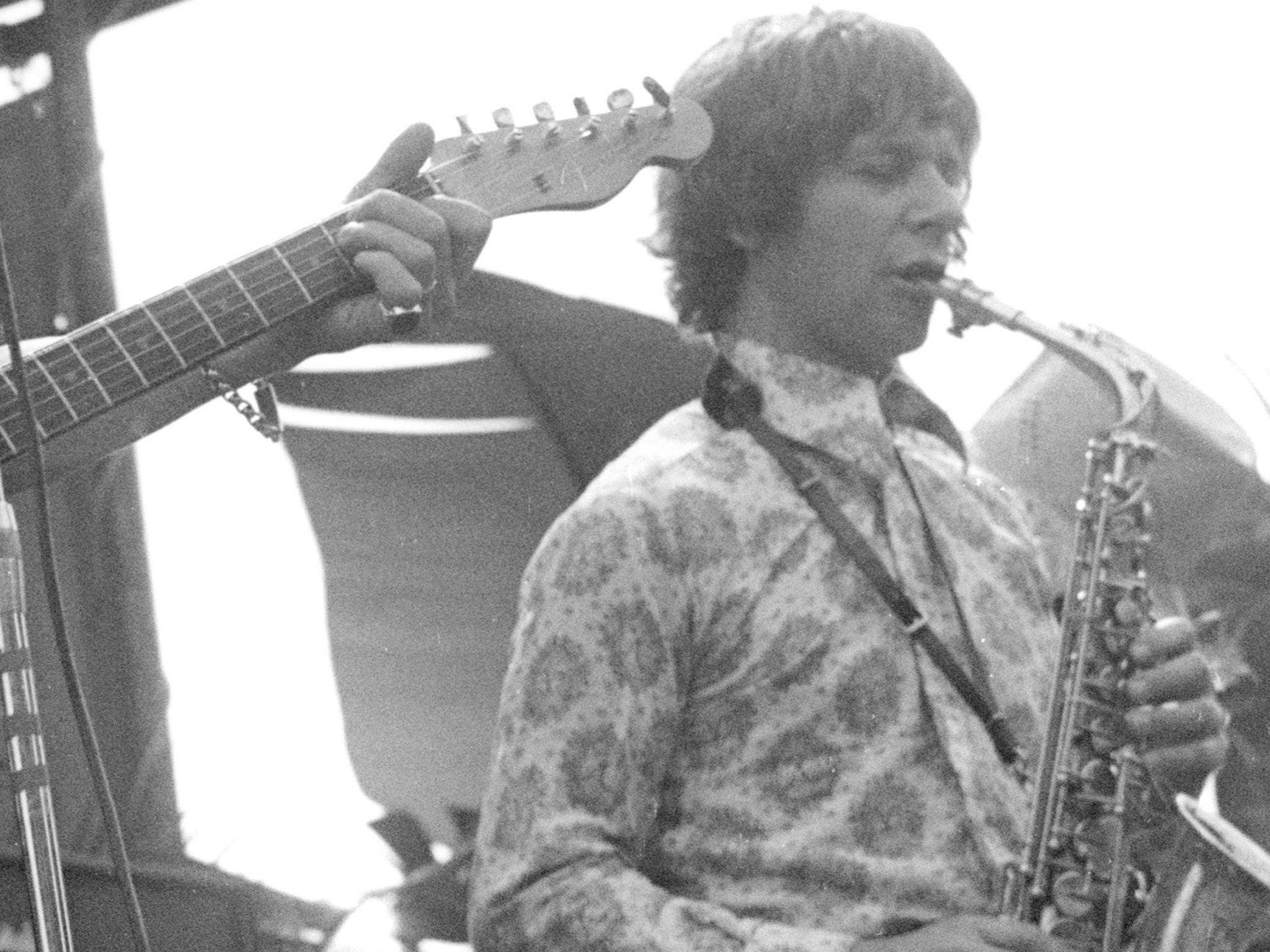

Ray Warleigh: Eclectic saxophonist who worked with jazz giants like Humphrey Lyttelton and pop greats like Scott Walker

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“To hear him play the blues was a special thing.” Evan Parker’s verdict on his friend and fellow-saxophonist sums up the reactions of those who worked alongside Ray Warleigh during a 65-year career in British jazz, rock and r’n’b. A self-effacing figure who always played for the band and for the music rather than for the spotlight, Warleigh had almost drifted out of sight as far as the record-buying public was concerned when Parker organised a 2009 studio date for him with studio drummer Tony Marsh. It yielded the CD Rue Victor Masse on Parker’s Psi label, a set that once again vividly demonstrated Warleigh’s perfectionism.

His cleanly articulated alto saxophone and flute lines fitted into a wide range of projects and styles. He was born in Sydney on 28 September 1938 (“the day peace ended”, he once said wryly, referring to the ill-fated Munich meeting called that day by Hitler) and arrived in London as a 21-year-old, just in time to meet the boom in blues-based music.

After that he never stopped working. His extraordinary CV included sessions for Alexis Korner, John Mayall and Long John Baldry, the three big stars of UK blues and r’n’b, while in jazz he played with Humphrey Lyttelton, Georgie Fame, modernist bandleaders like Mike Westbrook and Michael Gibbs, Dick Heckstall-Smith, drummer Tommy Chase (with whom he briefly co-led a group) and the Afro-British repertory band the Dedication Orchestra.

He also worked with such cultish figures as Scott Walker (who produced the unimaginatively and somewhat playfully titled Ray Warleigh’s First Album in 1968), and Nick Drake, adding beautifully etched saxophone to “At The Chime of a City Clock” and flute to “Sunday” on Drake’s jazz-tinged Bryter Layter LP.

And if these were mostly the fleeting associations of a valued session player, Warleigh also formed longer-standing partnerships, as with the Latin-jazz group Paz, with whom he worked for 40 years, and the folk-jazz group PC Kent. His long friendship – and rivalry in self-effacement – with the Canadian-born trumpeter and composer Kenny Wheeler yielded some of his most cherished musical moments, like his solo on Wheeler’s beautiful “Consolation” on Music For Large and Small Ensembles. Evan Parker talks of the profound “synergy” between Warleigh’s melodic sensibility and Wheeler’s challenging harmonic sequences.

Other great moments have to be truffled out of albums by other leaders. Warleigh solos exquisitely on Mike Gibbs’ “Sweet Rain” and “And On The Third Day”, from the Rhodesian-born composer/arranger’s eponymous first album, and he shows a fine instinct for burning hard bop throughout One Way, an underrated 1978 collaboration with Tommy Chase.

Despite failing health, Warleigh continued to work into his final year, attending Dedication Orchestra rehearsals and performing at a Kenny Wheeler memorial on crutches. However he kept his true condition, cancer, secret from all but the closest of friends, preferring to attribute his lameness to a trapped nerve. His own best memorial is the widely scattered body of work he laid down over 65 years, work that maps out many of the main threads and directions of contemporary British art and popular music.

BRIAN MORTON

Raymond Kenneth Warleigh, musician: born Sydney, New South Wales 28 September 1938; died London 21 September 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments