Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

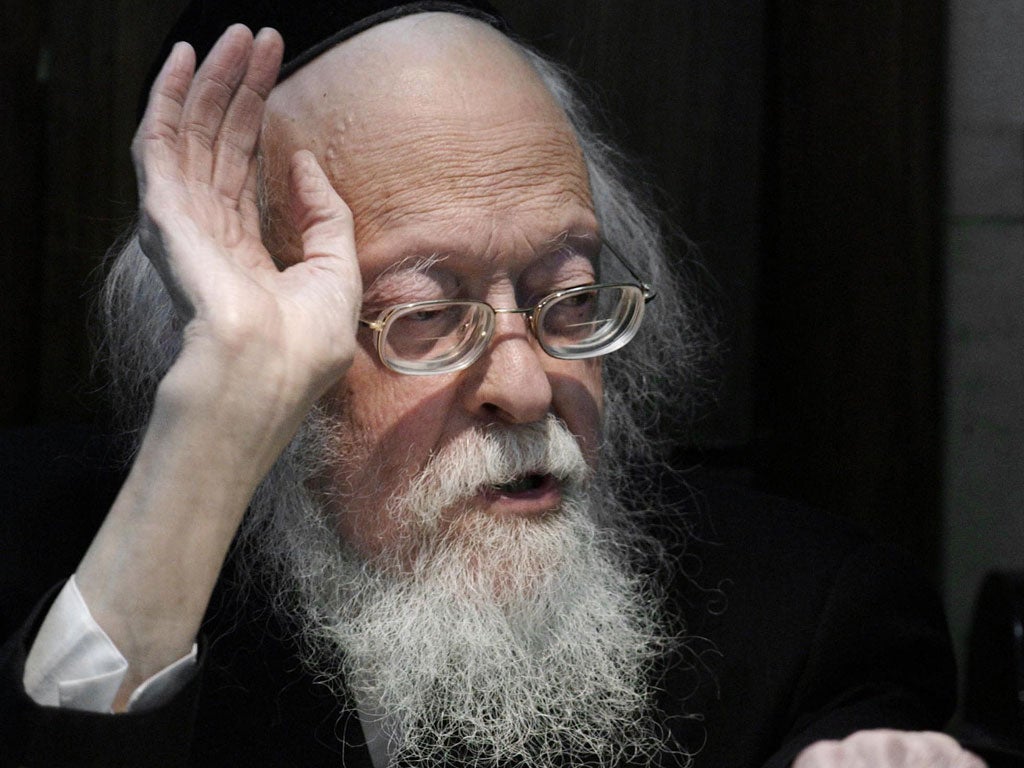

Your support makes all the difference.Rabbi Yosef Shalom Elyashiv, the highly influential leader of the Lithuanian sect of ultra-Orthodox Ashkenazi Jews, was known for his unyielding hardline rulings on complicated elements of Jewish law. As an eminent Posek, a decider of Jewish law, a title earned not by appointment but by scholarship, reputation and communal trust built up over decades, Elyashiv applied the Torah and Talmudic law to modern times, ruling on conversion, marriage, divorce and even the legitimacy of wigs made in India.

In the 1980s and 90s, Elyashiv clashed with the Israeli government when it arranged the conversions of thousands of immigrants from the former Soviet Union, arguing that a true conversion required a sincere pledge to observe the laws of Torah. Although he opposed Israel's 2005 unilateral withdrawal from the Gaza Strip, he instructed the political representative of the Degel HaTorah Party, with which he was affiliated, to support the then Prime Minister, Ariel Sharon, in pulling out the remaining settlers, many of whom were Orthodox.

Born in Lithuania in April 1910, Yosef Elyashiv was the son of Rabbi Avraham and Haya Mussa. He was, however, heavily influenced by his mother's father, the Kabalist Rabbi Shlomo Elyashiv, whose name the family adopted. When he was 12, the family emigrated to Palestine, then under the British Mandate, and settled in the Mea Shearim district of Jerusalem. Educated at Ohel Sara religious school, Elyashiv excelled and impressed the rabbinical elite with his concentration and logical analysis.

In 1950, Elyashiv became a judge in the state-established High Rabbinic Court, part of an official religious system that existed alongside Israel's secular courts. However, in 1974 this came to an abrupt end with his resignation, following a well-publicised case in which two children born in a second marriage were deemed able to marry ordinary Jews; Elyashiv vehemently disagreed with the ruling.

Elyashiv concentrated on the religious texts for between 16 and 20 hours a day, scarcely seeing his family. One of his daughters recalled, "When we were children, he didn't know us at all, he didn't speak to us, he would think of his studies the whole time."

In the 1990s, Elyashiv served as the spiritual leader of a small ultra-Orthodox party, Degel HaTorah, in the Israeli parliament, which later became the influential United Torah Judaism party, a grouping of religious parties that held the balance of power in many coalition governments and thus ensured concessions, such as keeping secular studies out of ultra-orthodox schools. In 2001, he became head of the Council of Torah Sages, the top policy-making body for ultra-Orthodox Ashkenazi Jews.

Crediting his longevity to never becoming angry, the stern, slender Elyashiv rejected worldly possessions and, beginning in the mid-90s, received thousands of visitors into his small, humble apartment. All sought advice, blessings and rulings on aspects of Jewish law and religious issues.

In rabbinical law, Elyashiv was strict, accepting only the narrowest of interpretations. For example, he refused to recognise the scientific phenomenon of brain death, making it impossible for his followers to donate organs; he banned human hair wigs from India (which Jewish Orthodox women wear, out of modesty, to cover their own hair) because the hair had been cut off in Hindu ceremonies. After his ruling, women in Jerusalem and elsewhere, notably in Brooklyn, burned thousands of wigs, replacing them with synthetic products.

Other rulings sought to resist modernity; he opposed academic degrees for women from the Bais Yaakov seminaries, the introduction of secular studies into religious schools, and opposed the state's attempts to enlist his followers to the Israeli military, as this would bring them closer to the secular lifestyle. He was a supporter of the Lithuanian ultra-Orthodox social system in which most adult males were encouraged to devote their life to religious studies rather than seek employment.

However, the ultra-Orthodox rank and file voted with their feet when Elyashiv prohibited the use of the internet and non-kosher mobile phones.

Martin Childs

Rabbi Yosef Shalom Elyashiv, religious leader: born Lithuania 10 April 1910; married Sheina Chaya Levin (died 1994; 12 children); died Jerusalem 18 July 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments