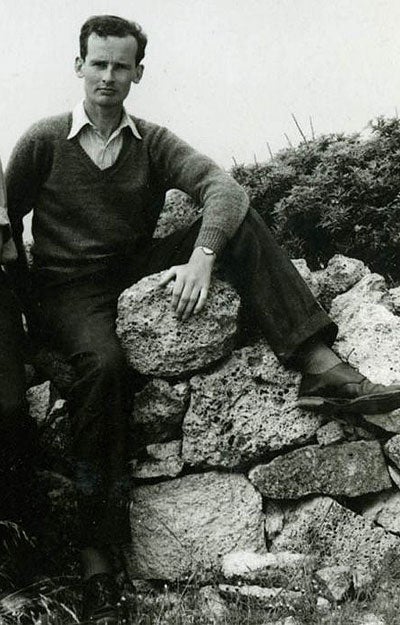

Professor Nicolas Coldstream: Pioneering investigator of Greek culture and history of the ninth and eighth centuries BC

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The archaeologist Nicolas Coldstream was a brilliant, and pioneering, investigator of Greek culture and history throughout the Mediterranean in the ninth and eighth centuries BC, the era of the early, pre-Classical city states, reintroduction of writing, emergence of the Iliad and Odyssey, start of Greek settlement in Italy and the west Mediterranean, and the first Olympic Games (776 BC).

He approached this seminal period in Western history through analysing and arranging the pottery of the different regions of Greece so as to create a framework for history and comparative study, that all have used ever since it appeared 40 years ago in his masterpiece Greek Geometric Pottery. ("Geometric" is the standard label for the pottery style he elucidated.) Study of pottery did not rest there. A workaholic, he kept adding to our understanding through articles, chapters and lectures until his sudden death, just days before the second edition came out, taking account of new finds and ideas since 1968. Pottery led on to early Greek history, where he wrote another extraordinary synthesis: Geometric Greece (1977, with its second edition in 2003).

As a scholar in the humanities, much of his authority came from a scientific sense of how "provisional" (his word in one preface) his – or anybody else's – ideas were. His writings show modesty, especially before the achievements of those Greeks of long ago in which he took an almost personal pride, a sense of involved irony that could move into empathetic playfulness about the ancient craftsmen and their patrons, and deep enthusiasm. To these add an elegant prose style, constant lucidity while aiming to let the reader judge for himself, and an excellent eye (the painter William Coldstream was his "Cousin Bill") and visual recall. I saw this first in the Thebes Museum in the mid-1960s. The guards would not allow him to sketch some Geometric pots, on the grounds they were unpublished. We left for a kafeneio. "Don't speak," he said – and promptly wrote out his notes, and drew sketches, from memory. Then it was time for ouzo.

Coldstream enjoyed being a son of the Raj, born in Lahore where his father was a High Court judge. But it entailed being sent back to prep school: he hated St Cyprian's, Eastbourne, as George Orwell had earlier (but Cyril Connolly quite liked it – see Enemies of Promise on "St Wulfric's").

Like both of them, he was then a King's Scholar at Eton, where a heavyweight election included the future Lords Kingsdown and Armstrong of Ilminster, and Sir Peter Swinnerton-Dyer. Coldstream found the institution tolerable only in his last years; one master, Francis Cruso, especially encouraged him in music. National Service in Egypt and Palestine was followed by King's College, Cambridge, where he took a double First in Classics, and there was much music.

Four years of teaching classics at Shrewsbury marked time before a one-year post at the British Museum, where he discovered the joy and challenge of Geometric pottery. So he started three years of research on this pottery at the British School at Athens, the UK's oldest foreign research institute, where he also began a deep connection with Knossos, taking on the excavation of the Sanctuary of Demeter under the School's Director, Sinclair Hood, and following the lead of Humfry Payne, James Brock and Vincent Desborough in showing by the practical ways of archaeology the long and important afterlife/continuation of the former Minoan capital. His 1973 publication of the shrine (Knossos: the sanctuary of Demeter) is a paradigm of how to identify an otherwise anonymous deity from the material remains of the cult ritual.

Coldstream returned to a lectureship at Bedford College, London, which led eventually to a chair, before moving to University College in 1983 as the Yates Professor of Classical Art and Archaeology. In both places he was renowned as a brilliant lecturer, teacher and supervisor, patient, clear and kind. If in his writing and lecturing he quietly emphasised the importance of not being a determinist but allowing for human quirkiness in explaining ancient culture and behaviour, he was the same teaching his students in encouraging them, and showing them how, to look at the evidence for themselves and realise that their ideas could be quite as valid as any professor's. Many were from Greece and Cyprus, whose people and places he loved. Many have contributed greatly to scholarship, thanks to his starting them off. Many now have senior posts. All loved him.

In 1963 he joined George Huxley in excavating an offshore Minoan settlement on the island of Kythera, between Crete and the Peloponnese, where – as usual – he made order out of the levels of Bronze Age occupation and their pottery, while the two of them followed the then new approach of describing an island world and the changing interactions of people and place diachronically through all antiquity, rather than hiving them off into artificial segments that had no relationship with each other.

In 1970 he married Nicola (Nicky) Carr, a leading scholar of medieval architecture and art, in a blessed union of minds and hearts that meant plenty of expeditions to Gothic buildings across the continent and as far as Cyprus, which offered research topics for both of them. In London they lived in the house where Mozart had stayed as a boy and, later, Vita Sackville-West lived. Whether for visiting foreign scholars or friends up from the country or from across town, their hospitality, chat, laughter, serious food and wine, and the chance of some music were a magnet, all the more for being so close to Victoria bus and train stations.

Knossos still called. A massive excavation in the late 1970s of its main Early Iron Age cemetery under Hector Catling, Director of the Athens School, led to an equally massive, and lucid, joint publication by Coldstream and Catling in 1996 (Knossos North Cemetery), after years of study visits by the Coldstreams, when Nicolas marshalled the vases – in their thousands – and Nicky drew them. It is a demanding task, but drawings often make clearer presentations than photographs.

Honours and invitations for prestigious lectures flowed, especially from the continent. Honorary doctorates could redeem no PhD: in the 1960s they were not always essential for a university career. A Fellow of the British Academy since 1977, in 2003 he received its Kenyon Medal for Classical Studies.

From Coldstream's teens, music mattered almost as much as archaeology: he played the piano in University College concerts and from 1984, realising his technique could improve, for over 20 years had a lesson every six to eight weeks with Ruth Nye of the Yehudi Menuhin School and the Royal College of Music. The formality of music matched his love of the formal Geometric style.

Nicolas Coldstream enjoyed company and rarely seemed without a twinkle, or deep laugh in commenting on egregious behaviour. He was quick to produce texts and exceptional in readily taking on tiring unpaid tasks, such as editing publications for the British School at Athens, or being chairman of and organising the big five-yearly conference of classical archaeologists when it came to London. He was always in demand for writing references. No surprise. He brought out the best in so many people, especially his students.

Gerald Cadogan

John Nicolas Coldstream, archaeologist and musician: born Lahore, India 30 March 1927; Assistant Master, Shrewsbury School 1952-56; Temporary Assistant Keeper, Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities British Museum 1956-57; Macmillan Student, British School at Athens 1957-60; Lecturer, Bedford College, London University 1960-66, Reader 1966-75, Professor of Aegean Archaeology 1975-83; FBA 1977; Yates Professor of Classical Art and Archaeology, University College London 1983-92 (Emeritus), Honorary Fellow 1993; married 1970 Nicola Carr; died London 21 March 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments