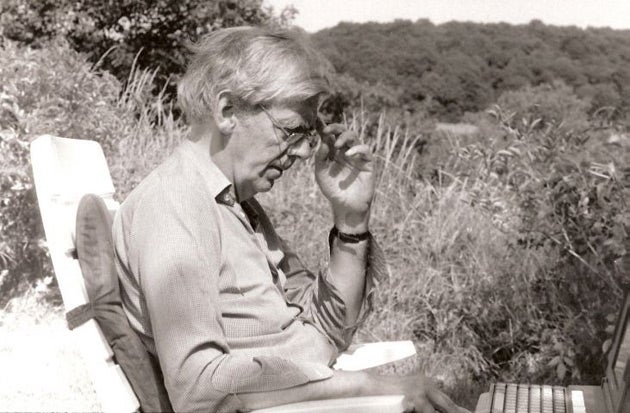

Professor Michael Baxandall: Influential art historian with a rigorously cerebral approach to the study of painting and sculpture

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Michael Baxandall was one of the greatest and most influential art historians of the second half of the 20th century, responsible for the introduction of ideas about language and rhetoric into the study of works of art and a key figure in establishing art history as a subject with its own intellectual rigour.

He was born in Cardiff in 1933 into an upper middle-class family with long connections to museums – his grandfather was Keeper of Scientific Instruments at the Science Museum and his father was Director of the Manchester City Art Galleries and the National Galleries of Scotland. He was educated at Manchester Grammar School and Downing College, Cambridge, where he read English and was much influenced by the works of William Empson and F.R. Leavis, by whom he was taught and who focused his interest on language.

After graduating, he went to study in Italy at the University of Pavia and in Germany at the University of Munich. His book The Limewood Sculptors of Renaissance Germany, published to great acclaim in 1980, was said to have originated in his time as a lonely postgraduate student seeking consolation in the museums of mid-1950s Munich.

On his return to London in 1958, Baxandall was offered a job by Gertrud Bing to work in the Photographic Collection of the Warburg Institute, and, the following year, he was awarded a Junior Research Fellowship at the institute, to study for a PhD on the notion of decorum and restraint in 15th-century Italy, under the supervision of Ernst Gombrich. The Warburg, where he met his wife, Kay, was to remain a spiritual and intellectual home, in spite of the fact that he could be occasionally sardonic about its characteristics and did not fit easily or comfortably into an intellectual school.

In 1961, Baxandall was appointed Assistant Keeper in the Department of Architecture and Sculpture at the Victoria and Albert Museum, where he worked for four years on German sculpture under John Pope-Hennessy as Keeper and, more especially, Terence Hodgkinson, the Deputy Keeper. He was not a natural museum type, but later claimed to like the disciplines of museum life and, slightly idiosyncratically, listed "antiquary" as his profession in his passport.

It was with relief that he was able to retreat to a university lectureship at the Warburg Institute in 1965, where he devoted himself to the research which was supposed to be for a doctorate, but was never submitted and which led to the publication of his first book, Giotto and the Orators, in the Oxford-Warburg series in 1971.

It is hard now to reconstruct the impact which both Giotto and the Orators, a book about how humanists wrote about art, and the immediately subsequent Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy (1972), had on the professional study of art history. Up until the early 1970s, most art history had been written from the viewpoint of connoisseurship and attribution, reconstructing the oeuvre of artists from surviving works of art.

Baxandall's approach was rigorously cerebral, studying works of art from the surrounding mental universe, humanist culture in the case of Giotto and the Orators and vernacular culture in Painting and Experience. He was happy to study account books and mathematical manuals and, most of all, books of rhetoric as a way of understanding how artists such as Giotto and Piero della Francesca, as well as their public (the distinction is never clear) viewed their world. The practice of art was viewed as an activity of the intellect at least as much as of the eye.

Following the publication of these two books, Baxandall was established as a major intellectual figure, invited to be Slade Professor of Fine Art in Oxford in 1974, where he lectured on German sculpture. But he resisted categorisation, did not particularly enjoy postgraduate teaching (although he was an inspirational figure to students), and could be wilfully obtuse in his attitude to methodology, as when he was invited by New Literary History to reflect on his approach to the writing of art history. Instead, as art history became increasingly recondite, Baxandall did not like to be associated with a movement towards over-conceptualisation and was an advocate of cool, intellectual rigour in opposition to the more self-consciously learned traditions of the Warburg.

Baxandall's greatest book was The Limewood Sculptors of Renaissance Germany, which won the Mitchell Prize for art history and in which he subjects an unfamiliar field of study to deep, systematic analysis, attentive as always to the relationship between language and form. He was awarded a chair by London University in 1981 and was made a Fellow of the British Academy in 1982, but was increasingly lured away to the United States, where he was appointed A.D. White Professor-at-Large at Cornell University, was given a MacArthur Foundation award, and became a half-time Professor of the History of Art at the University of California, Berkeley in 1987. From this point onwards he led a hybrid life, partly in London, partly in California.

In 1994, Baxandall wrote jointly with Svetlana Alpers Tiepolo and the Pictorial Intelligence and, the following year, under sole authorship, the book Shadows and the Enlightenment. Neither had quite the broad impact of his earlier work, although like all his work, they were the product of systematic and highly original thought.

By now, he was suffering from Parkinson's disease, which clouded the later years of his life, although he bore it with characteristic fortitude and continued to write and publish to the end, including, in 2003, Words for Pictures. It was perhaps this illness, along with his reclusive temperament, that prevented him from receiving the full recognition beyond the scholarly community that the quality of his intellect and the originality of his writing deserved.

Charles Saumarez Smith

Michael David Kighley Baxandall, art historian: born Cardiff 18 August 1933; Junior Research Fellow, Warburg Institute, London University 1959-61, Lecturer in Renaissance Studies 1965-73, Reader in History of the Classical Tradition 1973-81, Professor of History of the Classical Tradition 1981-88; Assistant Keeper, Department of Architecture and Sculpture, Victoria and Albert Museum 1961-65; Slade Professor of Fine Art, Oxford University 1974-75; A.D. White Professor-at-Large, Cornell University 1982-88; FBA 1982; Professor of the History of Art, University of California, Berkeley 1987-96 (Emeritus); married 1963 Kay Simon (one son, one daughter); died London 12 August 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments