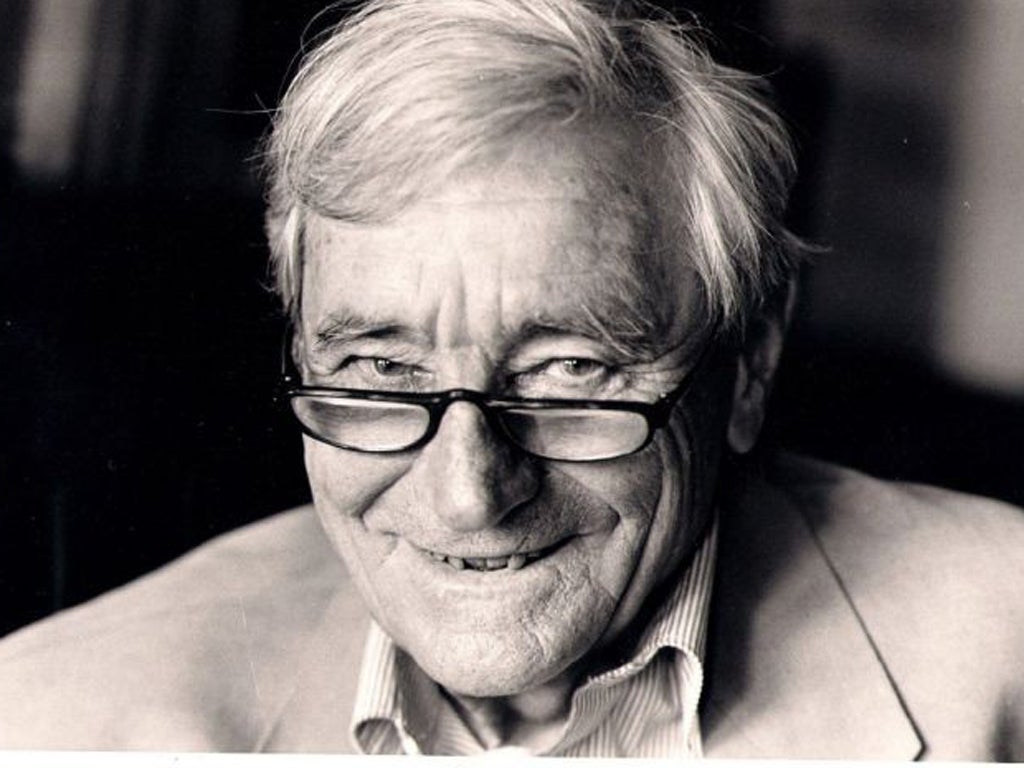

Professor Ian Little: Economist who urged pragmatic thinking on issues of overseas aid

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ian Little had the finest mind in post-war British economics. In the opinion of his Oxford contemporary Francis Seton he "combined the most rarefied forms of abstract thinking with a down-to-earth pragmatism". He is best known for his contributions to welfare and development economics.

But intellectual fastidiousness and a "take it or leave it" attitude, combined with difficult personal circumstances, prevented him from securing the recognition he deserved. Unpardonably, there is no entry for him in the New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics.

His upbringing and personal life are pitilessly described in his privately printed memoir, Little by Little, a remarkable essay in detached frankness. Born in December 1918, he was the sixth and last child of Iris and Malcolm Little. The Littles were soldiers who traced their descent to the Scottish king Robert Bruce. The money came from his maternal great-grandfather, Thomas Brassey, the railway builder, who was made an earl in 1911. Ian's childhood home, Dunstone, had 200 acres, 23 bedrooms and 20 servants. His parents were devoid of intellectual interests; family relationships were chilly: of his siblings, he was close only to his next brother Denis, who became a manic depressive.

He started to shine intellectually at Eton, but left school as soon as he had got his Oxford place to avoid a ritual called "Speeches", which involved public declamation. He never overcame a paralysing shyness. He read PPE at New College, Oxford and became interested in philosophy. But mostly he indulged in the standard rich-boy dissipations of hunting, gambling, drinking, and betting on horses: the probabilities of risk-taking fascinated him, and he became an excellent bridge and poker player. He concluded his studies in 1946.

Little had qualified as a pilot, but instead of being hurled into the Battle of Britain flew autogyros, almost stationary aircraft which transmitted signals about incoming enemy planes. He became a test pilot for experimental aircraft, "rota buggies", which sought to improve on parachutes by attaching rotor blades to people and trucks. He likened himself to James Bond trying out Q's inventions. He was awarded an Air Force Cross, but these contraptions gave him a fear of flying.

In 1946, he married Dorothy Hennessey, a technical assistant at the Ministry of Aircraft Production, after her divorce from a Mr Mandelson, who went on to marry a daughter of Herbert Morrison. ("If it had not been for me, Peter Mandelson would not have existed," Little remarked drily.) The first half of their marriage was marred by Dobs's drinking, but when she stopped in 1967 she became an assistant on research into drug abuse at the Ley Clinic in Littlemore, and practised there for five years. A trained economist, she assisted Little, and the second half of their marriage was serene.

Little did his postgraduate work in economics rather than in philosophy. He said this was because there was less competition in economics, philosophers being cleverer than economists. He was elected a prize fellow of All Souls in 1948. His Critique of Welfare Economics, the published version of his DPhil, appeared in 1950. It sold 70,000 copies over two editions.

Little used the tools of the dominant logical positivist philosophy of his day to demolish the claim that welfare economics can provide objective criteria of justice. What constitutes a just distribution is a value judgment. The Critique was in part a study of the use and abuse of influential and persuasive language in economics. The Critique established Little as a major theorist, and he succeeded his friend Tony Crosland as economics fellow at Trinity College, Oxford. A fellowship at Nuffield College, Oxford followed.

However, he decided that his "minimal mathematics" precluded him from making any contribution to economic theory. He therefore abandoned the borderland between economics and political philosophy which he had occupied so notably in his Critique, to the great loss of both disciplines.

Little was granted a two-year leave from Nuffield College to work in the Treasury, but his stint failed to lead to any further government jobs. In 1962-63 he organised seminars at Nuffield College for the Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer, Jim Callaghan, to teach him some economics. He recalled ruefully that Callaghan "tended to steer the argument into political channels before all the economic issues had been fully explored". At any rate, he failed to convince him of the virtues of devaluation. Thereafter his interest in domestic economic policy faded.

Development economics offered an escape. Following a trip to India in 1958 to investigate the benefits of nuclear power for poor countries, Little was asked by William Clark, head of the Overseas Development Institute, to write a book on African aid. Aid to Africa (1964) concluded that "no African country could beneficially absorb a large amount of capital aid" because of the lack of grassroots industrial and financial expertise, and inadequate central administration.

His Indian and African experiences did not at first shatter his faith in central planning; the problem was to get planning done better. As Vice-President of the OECD Development Centre in Paris from 1965-67 he initiated a research project on comparative trade and industrialisation; he and Jim Mirrlees developed new techniques of project evaluation, using social cost-benefit analysis. The essential principle they promoted was that in deciding whether to encourage domestic production, planners should take into account export prospects and whether goods could be imported more cheaply. This was anathema to those who considered free trade a colonial imposition to stop countries developing.

The main obstacle to the adoption of more rational methods of evaluation, he felt, was the prevalence of kickbacks in expensive projects. The failure of these investments to earn or save foreign exchange was a major cause of the debt crisis of the 1980s; Little believed that over-optimistic investment financed by foreign borrowing also played a part in the east Asia crisis of 1997-98. In the end he gave up hope that planners could be induced to behave rationally.

He was a spectacularly successful investment bursar for Nuffield College, concentrating on buying stocks with a good record of past earnings growth. Little became Professor of the Economics of Underdeveloped Countries in 1970 and was elected to the British Academy in 1973. However, his market-oriented approach to development fell foul of the Oxford development establishment. He also started to feel less at home in the mental atmosphere of Nuffield College, which, by the 1960s, saw itself as part of the new Labour establishment.

In the 1970s he gave up his professorship and fellowships. An invitation from his most famous pupil, Manmohan Singh, subsequently Prime Minister of India, to become economic adviser to the Indian government, was cancelled because of political unrest; instead he got a five-year appointment to the Development Section of the World Bank.

In the 1970s Little designed and built a retirement home in La Garde Freinet in Provence. But his married life there was brief; Dobs died in 1984.

Little's last major contribution to development economics was on the macroeconomic policies of developing countries, Boom, Crisis, and Adjustment (1993): "Countries should be fiscally prudent. They should not become very heavily indebted, especially with short-term obligations. They should be aware of huge, dramatic government-inspired projects."

In 1991, Little, who did not take kindly to renewed bachelorhood, married Lydia Segrave. She was a perfect partner; he was a loving and supporting stepfather to her two children, Jessica and Joseph. Little survived an operation for bladder cancer in 1984 and lung cancer in 1999. The second left him physically enfeebled, but his mind remained as acute as ever, and his skill at bridge undiminished.

Ian Malcolm David Little, economist: born 18 December 1918; married 1946 Doreen Hennessey (died 1984; one son, one daughter), 1991 Lydia Segrave (one stepdaughter, one son); died 13 July 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments