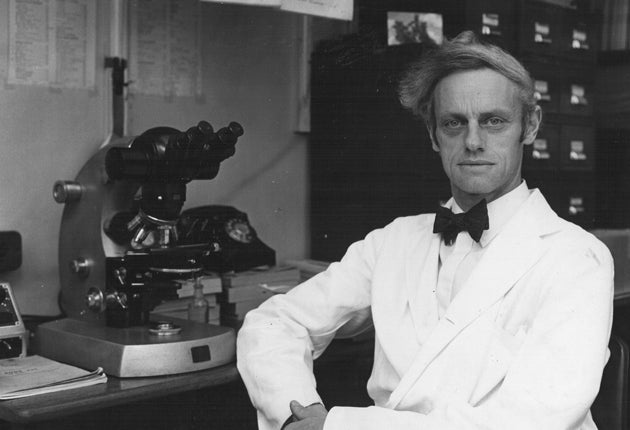

Professor Humphrey Kay: Haematologist who revolutionised the treatment of leukaemia

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Professor Humphrey Kay was a pioneer in the treatment of leukaemia and transformed the way doctors dealt with the disease.

When Professor Kay entered the field of oncology in the 1950s there was no effective treatment for any form of this disease.

But thanks to the work he pioneered and steered, by the mid-1980s most children with leukaemia, and a growing number of young adults, were being cured.

During his time at the Royal Marsden Hospital in London, his approach to his work was a combination of the practical and the intellectual. In 1963 he and his colleagues set about planning and building a ground-breaking new ward for the protective isolation of immune-suppressed patients with Kay as the administrator. So successful was this ward that they designed and built another, larger, one named the Bud Flanagan ward. It was equipped for the intensive treatment of acute leukaemia and designed to facilitate bone-marrow transplants. The ward was opened in 1973 and the first successful UK bone-marrow transplant was then performed.

While the wards were being set up, Kay was appointed as Secretary to the leukaemia trials of the Medical Research Council. Using his diplomatic flair, his extraordinary presentation skills and his charm, he managed to bring together leukaemia specialists from Britain, France and the United States so they could collaborate in the research and treatment of this relatively rare disease. His efforts led to the establishment of the first international protocols on the treatment of leukaemia. Kay recognised the importance of understanding the biology of leukaemia, actively encouraging and taking part in pioneering research into the immunological and chromosomal characteristics of leukaemia cells. These characteristics now play a crucial role in diagnosis, prognosis and treatment.

Humphrey Edward Melville Kay was born in Croydon, Surrey in 1923. At three months old his mother, a missionary doctor, took him back to the family home in India, where his father was an Anglican minister.

At their homecoming to Lahore his elder sister Fran, who was four at the time, recalled a brass band playing in honour of the arrival of her baby brother – a son to the Memsahib who, up until then, had only two daughters.

He remained in India for the first four years of his life until the family returned to Britain. Back in England, he attended the Downs prep school in Colwall, Worcestershire, where he was taught English by W.H. Auden. During his time there, the poet composed many songs for the school concerts – some of which, in retrospect, Kay and his contemporaries realised, had contained some amusing, if inappropriate, double-entendres.

An old boy of Bryanston, he recalled that in 1941 he and his good friend Michael Flindt had cycled from their school in Dorset to Southampton to take their preliminary medical exams. The night before this exam, one of the heaviest wartime air raids hit the city. As the bombs fell, the students hid in a downstairs room and, even though a nearby ceiling collapsed, they were unscathed. With neither gas nor electricity, they worked out that their practical exams the following day would be limited; he and Flindt both passed.

Kay's medical career began at St Thomas's hospital in London, where he qualified in 1945. By 1947 he had joined the RAF and was transferred to Aden. He recalls that it was "a happy, peaceful place, where one learned to avoid amoebic dysentery; to play tennis through the hot season; to ride a camel; and to admire the starry skies with a limited range of classical music on 78s with a wind-up player."

After returning to Britain, Dr Kay worked for six years in different branches of pathology (indeed 16 years later, he became the editor of the Journal of Clinical Pathology), and then in 1956 he embarked on his career at the Royal Marsden Hospital as a consultant clinical pathologist. The vacancy at the Marsden, a destination he had never contemplated, coincided with his daughter going to school almost next door, so this made up his mind. He thought he might stay for a year or two but ended up dedicating 28 years of his life to the hospital, retiring as Professor of Haematology in 1984.

On retirement from medicine, he effectively began a second career as a naturalist, drawing on his childhood love of wildlife and the environment. He was soon nationally renowned in this field, too. His colleagues recall that, even though he came to it late, he was a born naturalist with a sharp intellect, enquiring mind and keen eye and a committed enthusiasm for wildlife. He was a member of the Wiltshire Wildlife Trust and was elected to its Council in 1983. One of the Trust's most valuable fund-raising activities arose from his idea of a sponsored walk each May Day bank holiday from Avebury to Stonehenge

He was a familiar figure in Wiltshire in his floppy hats, or for more formal occasions a flamboyant bow tie. His speciality was entomology, but he took an interest in most conservation issues, and contributed to the badger and bovine TB issues through articles, correspondence and national debate – his views not always welcomed by government or by other conservationists. In 1996 he was awarded the Christopher Cadbury Medal by the national body of the Wildlife Trusts for his contribution to conservation.

Kay was a true polymath, as comfortable with the arts as he was with science, and passionate about opera, ballet and music. He was also an accomplished musician and poet. He published a volume of humorous and reflective verse, Poems Polymorphic. One of these, "The Haematologist's Song", had a refrain of "Blood, blood, glorious blood..." set to The Hippopotamus tune of Flanders and Swann. He would sing it with great aplomb to delegates at national and international haematology meetings.

Kay survived his first wife, April, a consultant cheumatologist, who died in 1990, and leaves his second wife, Sallie, his children, stepchildren and many grandchildren.

Humphrey Edward Melville Kay, haematologist and naturalist: born Croydon, Surrey 10 October 1923; Junior appointments, St Thomas's Hospital 1950–56; Haematologist, Royal Marsden Hospital 1956–84; Professor of Haematology, University of London 1982–84 (Emeritus); Secretary, Medical Research Council Committee on Leukaemia 1968–84; Dean, Institute of Cancer Research 1970–72; editor, Journal of Clinical Pathology, 1972–80; Council, Wiltshire Wildlife Trust 1983–96; married 1950 April Powlett (died 1990; one son, two daughters), 1996 Sallie Perry (one stepson, one stepdaughter), died Marlborough, Wiltshire 20 October 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments