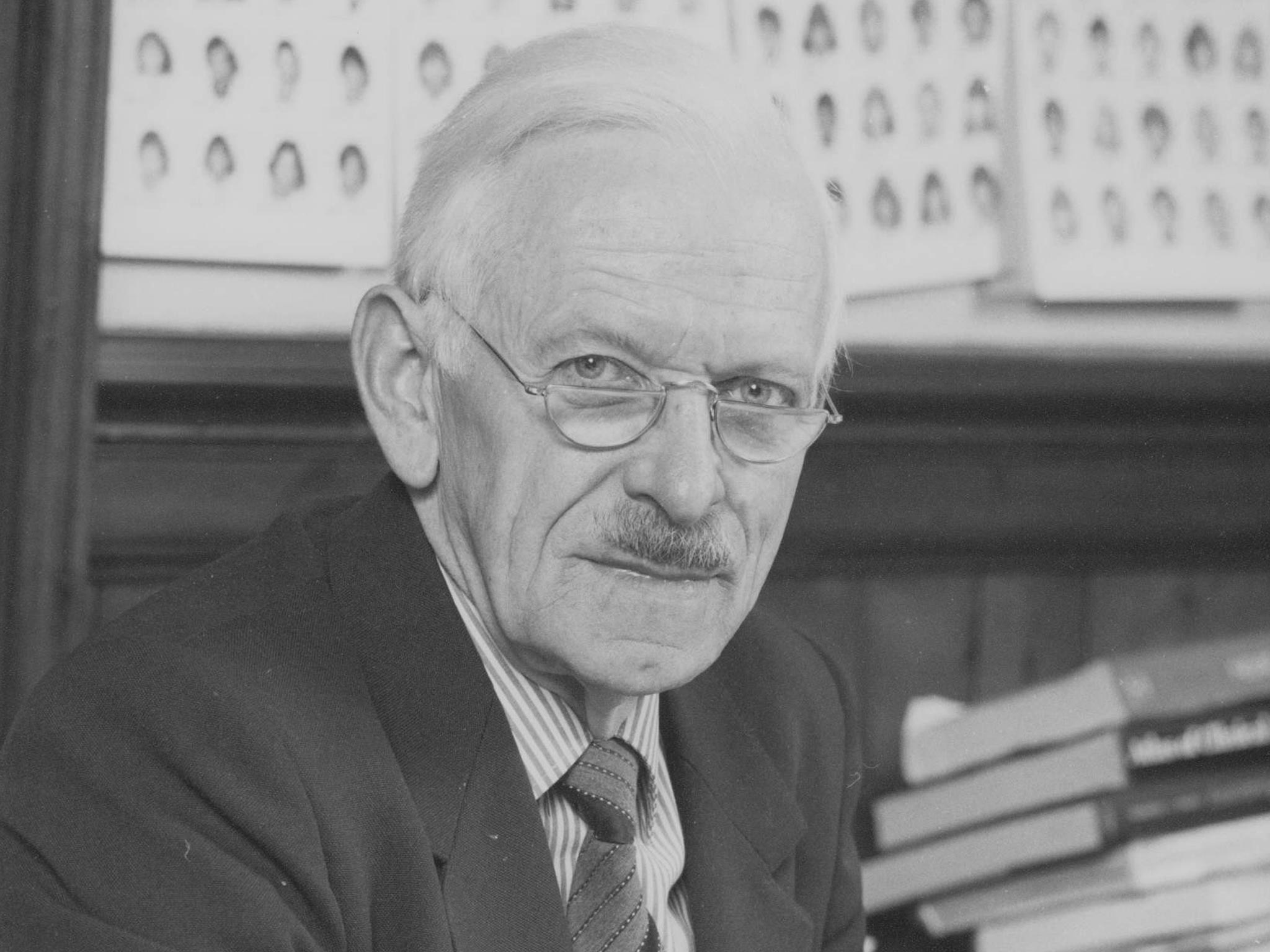

Professor George Romanes: Acclaimed medical scholar whose teaching abilities became legendary for two generations of students

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.George Romanes is etched into the fond memory of two generations of British doctors, his students in Edinburgh now dispersed over the UK and abroad. As a teacher he was superb, and a legend.

James Garden, Regius Professor of Clinical Surgery at the University of Edinburgh, told me he was an inspirational lecturer, a hands-on team leader in the dissection room and an active supporter of Garden and his contemporaries when they were young demonstrators in anatomy. Chris Haslett, Professor of Clinical Sciences at the Centre for Inflammation Research at the University, told me that Romanes' lectures, with their fantastic coloured anatomical designs on the blackboard were the highlight of his undergraduate teaching experience.

When I was an MP I approached Romanes in his capacity as Dean of the Faculty of Medicine about the case of a young medical student from West Lothian. He could not have gone to greater personal trouble, phoning me late at night to resolve the situation. One former student recalled to me Romanes' kindness in interrupting her during a pass/fail examination, so that as a nervous 18-year-old she had time to gather her thoughts and give a correct, unflustered answer. Yet the same Romanes was formidable with his senior colleagues, and even so assured a Vice-Chancellor as Michael Swann was careful how he handled him.

The son of an engineer, Romanes went to Edinburgh Academy and won a scholarship to Christ's College, Cambridge. There he was taken under the wing of the Master, Canon CE Raven, progressing to a PhD and becoming a Demonstrator in Anatomy. In 1940 he joined the Royal Army Medical Corps then returned briefly to Cambridge as a Beit Memorial Fellow in medical research.

His Edinburgh contemporary, Sir John Crofton (Independent obituary, 5 November 2009), Professor of Respiratory Medicine, told me that he and Romanes learned to be decisive on the battlefield, making life-and-death decisions as to who was lost and who could be saved. Romanes said he tried to inculcate a quality of breezy decisiveness into his students.

In 1946 he returned to his native city as a lecturer in neuroanatomy, his research enhanced by the experience of a Commonwealth Fellowship at Columbia University in New York, which led to what Garden called Romanes' "remarkable command of comparative anatomy". He would walk into a lecture theatre with no aids and a clean blackboard. He would proceed to paint with his coloured chalks a veritable 3D image of a particular part of the anatomy. For 30 years from 1954 he was what several of his students have recalled to me as an icon of undergraduate medical teaching.

Romanes' most important contribution to anatomy was perhaps not the flow of distinguished articles but his persistent updating of Cunningham's Manual of Practical Anatomy. He also brought a number of classic textbooks up to speed with the latest research, particularly in embryology and developmental anatomy.

A sense of his work can be given by some of his articles: "The spinal accessory nerve in the sheep", "Cell columns in the spinal cord of a human foetus of 14 weeks", "The development and significance of the cell columns in the ventral horn of the cervical and upper thoracic spinal cord of the rabbit", "The spinal cord in a case of genital absence in the right limb below the knee", "Some features of the spinal nervous system of the foetal whale"; and "Motor localisation and the effects of nerve injury on the ventral horn cells of the spinal cord".

If Romanes' performance in the venerable and historic old anatomy lecture hall were pure theatre, he also believed in and led teaching in the dissection room. In this he had a Conan Doyle-like admiration for his predecessor – and Sherlock Holmes' mentor – the legendary Dr Joseph Bell. In my contact with them as Rector of Edinburgh University (2003-06) several now senior members of the Medical Faculty told me of the debt they owed Romanes for his support for them as junior teachers and demonstrators, both financially and professionally, and his efforts to enable them to link their basic human anatomy with clinical practice in the city's Royal Infirmary. He was frequently asked by other British universities to give advice on the development of their medical schools.

Romanes mellowed somewhat. Alec Currie, the powerful Secretary of the University and Romanes' contemporary, described him to me as a "force for good – a kenspeckle and genial father figure at meetings of the Senate and Court." Currie recalled how he would grout his pipe, light up and make an authoritative comment which was almost always accepted as university policy.

Towards the end of his life Romanes recognised that the pendulum of medical education had swung away from the study of anatomy but sighed, "But for the better?, I wonder." Retiring to his beloved Loch Carron, he became no mean player on the curling rink, which involved endless calculations suited to his character.

Professor Gordon Findlater, Romanes' last appointment before he retired, told me that he visited Romanes at Loch Carron and was astonished to find that as a mid-nonogenarian he was building poly-tunnels for his exotic tropical plants and scaling his roof to adjust his television aerial.

TAM DALYELL

George John Romanes, anatomist: born Edinburgh 2 December 1916; CBE 1971; married 1945 Muriel Grace Adam (died 1992; four daughters); died Isle of Skye 9 April 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments