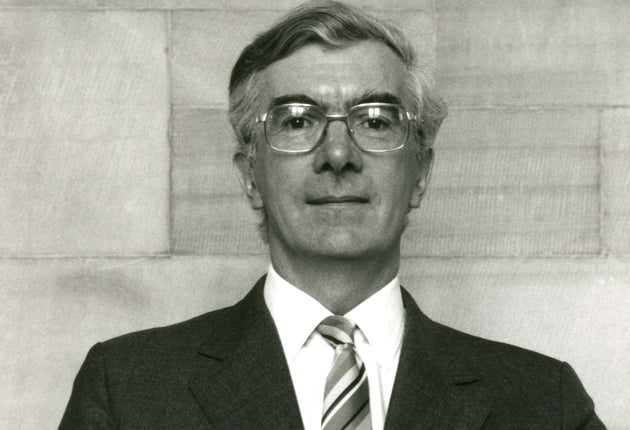

Professor Eric Sunderland: Vice-Chancellor of Bangor University who brought calm after a period of turbulence

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Few who witnessed the results of the referendum on Welsh Devolution late on the night of 18 September 1997 will forget the evident relish with which Professor Eric Sunderland, the Chief Counting Officer, announced that the Yes campaign had won by a slim but sufficient majority of 6,721 votes and that the proposal to establish a National Assembly was therefore approved by the people of Wales.

The clip has been shown over and over again on television in Wales, and the excitement and historic significance of the occasion, together with the Professor's beaming face, have entered the iconography of recent Welsh politics. It was as if Wales had scored a winning drop-goal in the closing minutes of an international rugby match and the roar was deafening; it gave him special satisfaction that the very last Yes result, which clinched the matter, came from Carmarthenshire, his native county.

Born at Blaenau, near Ammanford, in 1930, he went from Amman Valley grammar school to the University College of Wales, Aberystwyth, where he took a first in Geography and Anthropology, and then a master's degree; he was later awarded his doctorate by University College, London. After military service, he worked for a year as a research scientist with the Coal Board, but took his first academic post in 1958 as a lecturer in the Anthropology department of Durham University, where in due course he was appointed Professor and Head of Department in 1971; he also served as Pro-Vice-Chancellor from 1979 to 1984.

By the time he returned to Wales in 1984 he had a reputation as an anthropologist of distinction, having published such substantial books as Elements of Human and Social Geography: some anthropological perspectives (1973), Genetic Variation in Britain (with D. F. Roberts, 1973) and The Exercise of Intelligence: biosocial preconditions for the operation of intelligence (with Malcolm T. Smith, 1980), to which he later added Genetic and Population Studies in Wales (with Peter S. Harper, 1986). He had also held some of the most important posts in his specialist field, including those of Honorary Secretary of the Royal Anthropological Institute, Secretary General of the International Union of Anthropological and Ethnological Societies and Chairman of the Biosocial Society.

His appointment as Principal at Bangor in 1984 followed a turbulent phase in the history of the University College of North Wales, as it then was, and much was expected of the new man in healing the schisms caused by his predecessor, the autocratic Sir Charles Evans, whose tenure had come to what Dr David Roberts, Bangor's Registrar, in his history of the institution published in 2009, called "a bitter and querulous end". Evans, best-known for his role as deputy leader of the team that conquered Everest in 1953, had shown "a cold indifference" to the wider use of Welsh in the college's affairs and, moreover, had been highly unpopular among both staff and students during these "dark and divisive days, the darkest in the University's history", on account of his vindictive attitude towards those who disagreed with him.

Eric Sunderland, like his predecesssor a Welsh-speaker, was much better disposed towards the growing demand for teaching in Welsh, his first language, which he spoke fluently and elegantly, and in this and many other ways he proved to be the very antithesis of Evans. Although a patriotic Welshman, it had taken some persuasion to entice him from Durham, where his family was happily settled, but in the end he accepted the post with pleasure and took office just weeks before the college's official centenary celebrations. The appointment proved a popular one and, with his genial personality and abundant communication skills, he soon won over a wide swathe of the academic staff.

At ease in social gatherings, and ably supported by his wife, Patricia, he took his role as ambassador for the college seriously and few could fail to respond to his broad grin and friendly nature. He even made a point, early in his principalship of going to speak to students at Neuadd John Morris-Jones, the hostel for Welsh-speakers where many of those who had been protesting against the former principal were housed, thus spiking the guns of the Young Turks who had been disrupting the campus. His lecture "Esblygiad Dyn" ("Man's evolution"), delivered at the National Eisteddfod in 1985, demonstrated his ability to treat complex scientific topics in his first language.

Slowly the acrimony began to subside and a new mood of optimism started to be felt. Even so, and despite some gratifying achievements, Sunderland had to preside over a raft of administrative problems, not least those having to do with funding cuts by the UGC, and some hard choices about whether to maintain teaching in certain disciplines. This he did with sympathy and common sense and always with regard for the human cost involved. Despite his warm engagement with people, he had a tough inner core which stood him in good stead in the piranha pools of academe. That the college survived the troubled years of the 1970s and 1980s and the financial stresses of the 1990s was in large measure due to him and his senior officers.

Sunderland also played an active part in public life, and served on myriad bodies across the UK, where his skills were always appreciated. In Wales alone he was Chairman of the Local Government Boundary Commission (1994-2001), a member of the Welsh Language Education Development Committee (1987-94), the British Council (1990-2001), the Court of Governors of the National Museum (1991-94), and the Broadcasting Council (1996-2000).

He was keenly interested in the arts: he was chairman of the Welsh Chamber Orchestra, vice-president of the Welsh Music Guild, and patron of Artworks Wales. I first met him when he was chairman of the Gregynog Press Board in the 1980s, where we often talked about our love of books and fine editions in particular. After his retirement he liked nothing better than attending concerts at the University and was involved in fostering its art collection.

Many honours came his way, including the Mahatma Gandhi Freedom Award from the College of William and Mary in Virginia (1989). He served as High Sheriff of Gwynedd (1998-99) and Lord Lieutenant of the county from 1999 to 2006, and was awarded the honorary degree of LLD by the University of Wales in 1997 and the Queen's Golden Jubilee Medal in 2002.

Eric Sunderland, anthropologist and Vice-Chancellor of Bangor University: born Blaenau, Carmarthenshire 18 March 1930; Professor of Anthropology, University of Durham (1971-79); Pro-Vice-Chancellor, University of Durham (1979-84); Principal, later Vice-Chancellor, University College of North Wales, later Bangor University (1984-95); Emeritus Professor, University of Wales; married 1957 Patricia Watson (two daughters); OBE 1999; CBE 2005; died Beaumaris, Ynys Môn 24 March 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments