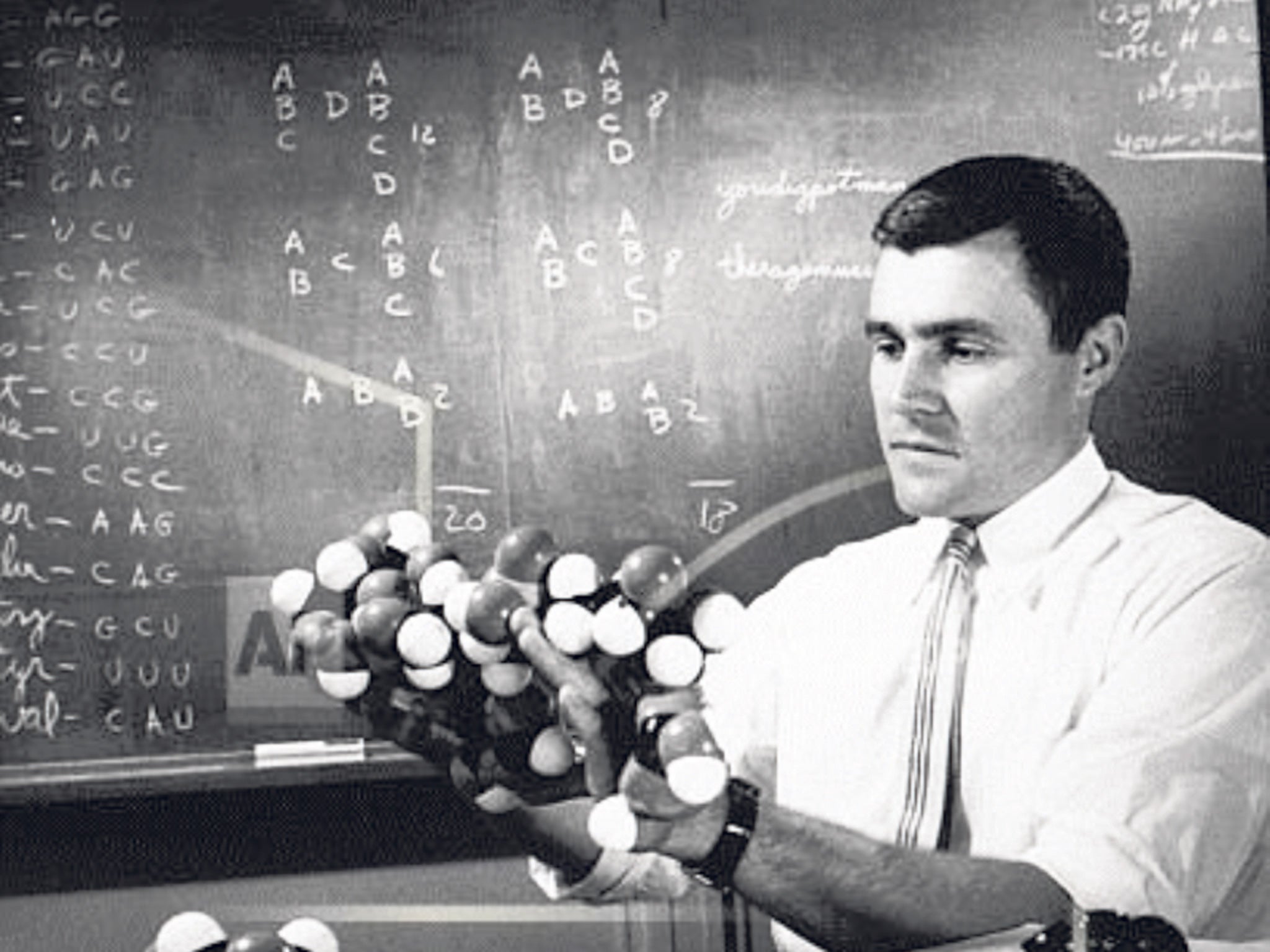

Professor Carl Woese: Scientist whose work revealed the 'third domain' of life

Carl Woese was a biophysicist and microbiologist who uncovered the "third domain" of life, with the detection of archaea. In doing so he redrew the taxonomic tree and proved that all life on Earth is related.

In 1977, Woese and his colleague George Fox published two papers that stunned the scientific world and overturned the universally held assumption about the basic structure of the tree of life. They concluded that microbes known as archaea are as distinct from bacteria as plants and animals. Before this, scientists had grouped archaea together with bacteria, and asserted that the tree of life had only two main branches – bacteria (called prokaryotes), and everything else, including plants and animals (eukaryotes).

The Stanford microbiologist Justin Sonnenburg said, "The 1977 paper is one of the most influential in microbiology and arguably, all of biology. It ranks with the works of Watson and Crick and Darwin, providing an evolutionary framework for the incredible diversity of the microbial world."

Woese noted that microbes, although invisible, comprise far more of the living protoplasm on Earth than all humans, animals and plants combined. Yet little research had been carried out on them. "Imagine walking out in the countryside and not being able to tell a snake from a cow from a mouse from a blade of grass," he said. "That's been the level of our ignorance." Woese worked out the early form of evolution by studying the genetic codes, or sequences, of different types of cells. He developed a DNA fingerprinting technique to show his finding.

In Woese's taxonomic redrawing, his three-domain system, based on genetic relationships rather than obvious morphologic similarities, divided life into 23 main divisions, incorporated within three domains: bacteria, archaea and eukaryota. He created a metric for determining evolutionary relatedness.

The discovery stemmed from years of analysis of ribosomes, protein-building structures abundant in all living cells. Rather than classifying organisms by observing their physical traits, as others had done, using ribosomal DNA, Woese looked for evolutionary relationships by comparing genetic sequences. He focused on a sub-unit of the ribosome, and found that the ribosomal sequences of some methane-producing microbes formed a new group distinct from bacteria and all other organisms – the archaebacteria, later shortened to archaea. He established that archaea, previously thought to be within the prokaryote group, had in fact evolved separately from a universal ancestor shared by all three groups.

Archaea, which are genetically relatively simple, were initially believed to exist only in extreme environments such as undersea volcanic vents and hot springs. However, since Woese's initial research they have been discovered in many places, including in plankton and in the human body.

Woese encountered some ridicule and found his work misrepresented by creationists, who claimed that evolution was a theory in crisis. Woese derided their views, saying: "Intelligent design is not science. It makes no predictions and doesn't offer any explanation whatsoever, except for 'God did it'."

A former colleague believed, "He turned a field that was primarily subjective into an experimental science, with wide-ranging and practical implications for microbiology, ecology and even medicine that are still being worked out."

Born in Syracuse, New York, in 1928, Woese obtained a BA in mathematics and physics from Amherst College in Massachusetts in 1950. He completed his PhD in biophysics at Yale. After a post-doctoral appointment at the University of Rochester studying medicine, he returned to Yale, spending the next five years as a researcher in biophysics, while also working as a biophysicist at the General Electric Research Laboratory in Schenectady, New York. In 1964, he joined the University of Illinois as a professor of microbiology, where he spent the rest of his career.

Described as "the most pure of scientists", he was committed to dissemination of scientific knowledge and was a member of the National Center for Science Education because he believed that secondary school biology teaching was poorly taught and needed overhauling.

Woese received numerous awards, including a MacArthur Foundation "genius" award in 1984, the Leeuwenhoek Medal (microbiology's principal honour) from the Dutch Royal Academy of Arts and Science in 1992 and the National Medal of Science in 2000.

In 2003, he received the Crafoord Prize in Biosciences from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, considered the equivalent of the Nobel Prize for areas of science that fall outside of the main Nobel categories; this award finally recognised his "discovery of a third domain of life". Many microbial species, such as Pyrococcus woesei, Methanobrevibacterium woesei, and Conexibacter woesei, are named in his honour.

Carl Woese, microbiologist: born Syracuse, New York 15 July 1928; married Gabriella (one daughter, one son); died Urbana, Illinois 30 December 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks