Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI: Former pontiff once dubbed ‘God’s rottweiler’ whose resignation was historic

The man born Joseph Ratzinger spent many decades as a key figure in Catholicism, writes Paul Vallely, but his choice to end his eight years as head of the Church and become Pope Emeritus will live longest in the memory

History may well judge that the most important contribution Joseph Ratzinger made in his 50 years as a key figure in the Catholic Church was to resign as pope.

That may sound a perverse judgement on a man who did so much else. In his youth he was one of the key radicals who helped shape the Second Vatican Council, which redefined the relationship between the Church and the modern world. Later in life he was, for two decades, Rome’s doctrinal watchdog – “God’s rottweiler”, as he was dubbed – cracking down on any deviation from conservative orthodoxy.

As pope he waged war on liberalism within the Church, holding the line against changed social attitudes on a range of totemic issues from bioethics to gay marriage. But Benedict XVI’s decision to become the first pope voluntarily to renounce his office in 600 years and become Pope Emeritus was a revolutionary act. It did not just stun the Church. It radically reshaped it.

By quitting, Benedict redefined the role of pontiff. What had for centuries been seen as a divine consecration was reconceived as a job. In Benedict’s own words: “If a pope clearly realises that he is no longer physically, psychologically and spiritually capable of handling the duties of office, then he has a right and, under some circumstances, also an obligation to resign.”

That has set an extraordinary precedent and, ironically, has perhaps done more to bring Roman Catholicism into the modern world than even the audacious acts of humility of his successor Pope Francis. It was not what anyone could have expected when Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger was born the third child of an extremely devout Catholic couple in Bavaria on 16 April 1927.

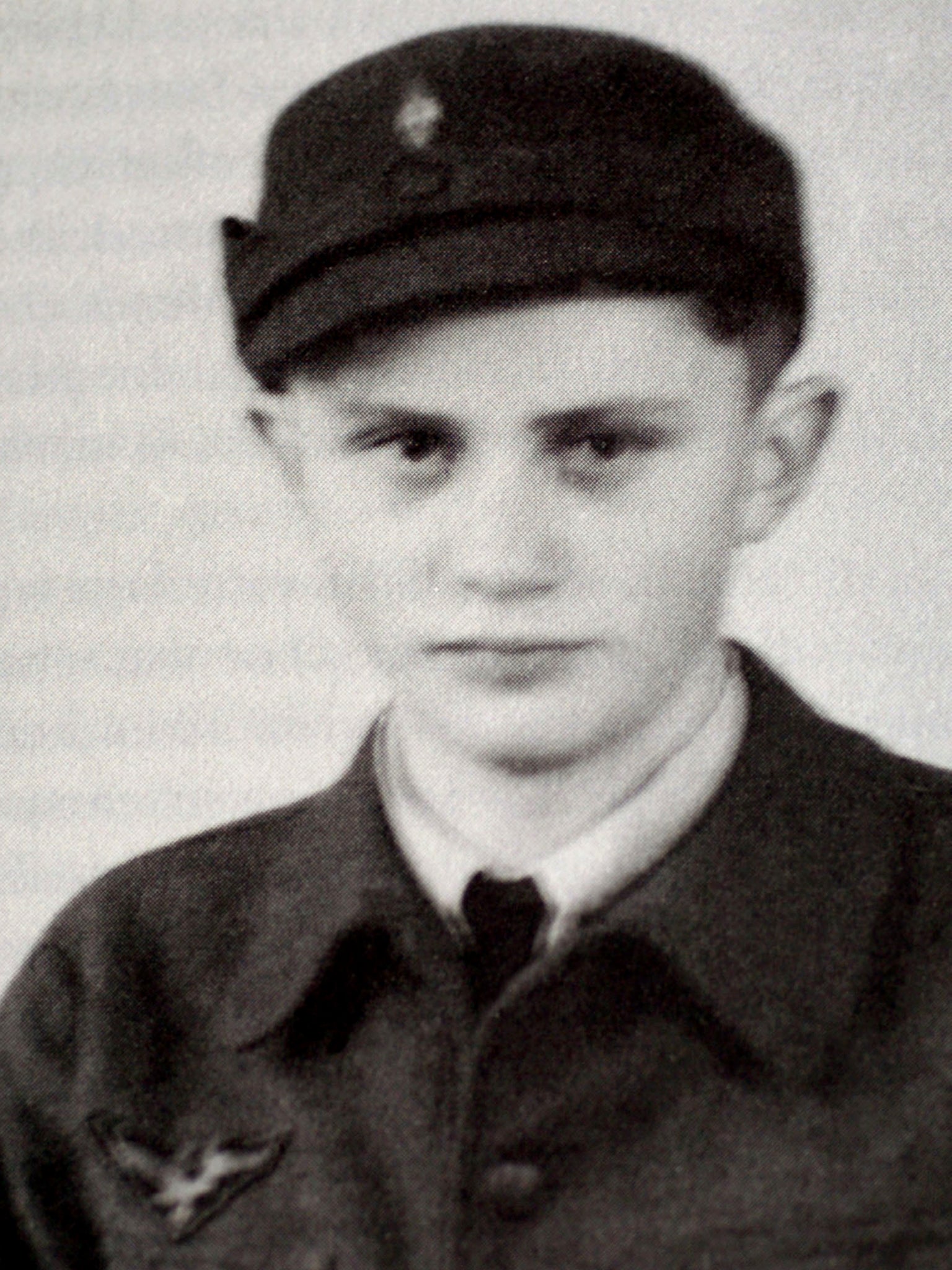

His parents’ names were Mary and Joseph (which provoked repeated jokes in his later life). His father was a police officer in Hitler’s Germany, whose outspoken criticism of the Nazis forced the family to move several times to increasingly more remote locations. At the age of 14, the shy and sensitive young Ratzinger was forced by law to join the Hitler Youth.

As the Second World War reached its height, the young Ratzinger was taken from the seminary where he was training to become a priest and drafted into an anti-aircraft unit – in the telecoms section, so he never fired a shot – and then into the German infantry.

Towards the end of the war he deserted and fled to the family home. As a former soldier, he was arrested by American troops and interned briefly in a prisoner of war camp. But with the end of the hostilities came an end to the distractions from his long-held intention to become a priest. He was ordained, with his elder brother Georg, in 1951. He was a youthful high flier. While still at work on his doctoral dissertation, he was made a professor of dogmatic theology at the University of Freising. A series of promotions swiftly followed at increasingly prestigious universities in Bonn, Munich, Tubingen and Regensberg.

Such was his standing as the bright new hope of German theology that he was recruited by the progressive Archbishop of Cologne, Cardinal Joseph Frings, as his personal adviser, or peritus, at the opening of the Second Vatican Council in 1963. Ratzinger’s hand was clear in a speech by Frings, which stunned the Church by attacking the most powerful of the congregations in the Roman Curia, the Holy Office – once known as The Inquisition. He called it “a source of scandal”.

Ratzinger was a decisive figure in drafting key Vatican II documents. He was vocal in his support for greater collegiality, giving bishops around the world a greater voice in the running of the Church. He was a founder of the progressive journal Concilium, along with some of the 20th century’s most prominent theologians like Hans Kung, Edward Schillebeeckx and Karl Rahner. But the man who was one of the stellar figures of reform within the Church then underwent a dramatic conversion from progressive to reactionary.

From early on he harboured reservations about Vatican II, fearing that there were some intent on sweeping away treasured elements of Church tradition in the name of “the spirit of the Council”. His fear of change was crystalised during the protests that swept through Europe’s universities in 1968.

By this time Ratzinger had been elevated, in 1977, by Pope Paul VI, to be Archbishop of Munich. It was a surprising appointment to many since Ratzinger’s pastoral experience had been limited to 15 months as a country curate. But in 1975 Ratzinger had written an article, on the 10th anniversary of the close of Vatican II, in which he set out a middle way between progressive and traditionalist interpretations of the Council.

The following year a little-known Polish cardinal preached a retreat to Pope Paul VI. Within a few months of being made an archbishop, Ratzinger had also been made a cardinal. Barely a year later Paul VI died and Ratzinger found himself as an elector at his first papal conclave. There he clicked with another new arrival, the Polish cardinal Karol Wojtyla – the man who had preached the retreat to Paul VI.

After the short-loved interlude of the papacy of John Paul I, which lasted only 33 days, a second conclave elected Wojtyla as Pope John Paul II. The Polish pope invited his new friend Ratzinger to Rome as Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF), the successor to the former Holy Office that Ratzinger had denounced as a young man.

After resisting the offer initially, Ratzinger went to Rome in 1981 to take the job. The poacher had turned gamekeeper. Over the more than two decades that followed at the CDF, Ratzinger cracked down hard on liberalism in the Church. Debate became redrawn as dissent. Free-thinking scholarship was condemned as corrosive.

Ratzinger went further than censuring critics. In the years that followed his CDF issued a series of insensitively-worded documents on the “intrinsic immorality” of gay sex. He led the Vatican in blunt dismissals of non-Christian religions and even characterised other Christian denominations as “gravely deficient”.

When in 2005 John Paul II died, Ratzinger was well-positioned to succeed him as pontiff. Moreover, though the voting cardinals had not met in conclave for 27 years and did not know one another well, they all knew Ratzinger for they all had to visit him at the CDF on official visits to Rome.

A talented linguist, and a man with considerable personal charm, he was able to address them by name and in their own language at the pre-conclave discussions on what was required from a new pope. As Dean of the College of Cardinals, he chaired those meetings, in a surprisingly collegial style that gave liberals hope he might change, and also preached impressively at John Paul II’s funeral and at the pre-conclave Mass.

To the electors he seemed the obvious candidate – a figure of continuity but now demonstrating a more collaborative style, it seemed. On 19 April 2005 he was elected pope in one of the shortest conclaves of modern times.

As Pope Benedict XVI, he did indeed cut a different figure than he had as head of the CDF. His name was chosen, he announced, because Benedict XV had been a reconciler and a peacemaker. The Vatican “rottweiler” was to become a gentler German shepherd. Immediately, as if to consolidate the legacy of his predecessor, he announced that he was fast-tracking Pope John Paul II on the road to being made a saint, without the usual five-year waiting period. But points of difference arose between the two papacies.

At the final Mass before the conclave, Ratzinger gave a sermon that set out what was effectively a manifesto for the Benedict papacy. The world, he proclaimed, needed a return to fundamental Christian values to counter a tide of increased secularisation, which promoted materialism and demoted absolute truths to subjective values.

This attack on moral relativism was a repeated theme in the score of visits he carried out over the next seven years in Europe, Africa, North and South America and Australasia. But his approach was that of a teacher in dialogue with his students rather than uncompromising authoritarianism.

His state visit to the UK in 2010 was a case in point. Months of high-profile media coverage of priestly sex abuse provoked predictions of a hostile reception. But these proved unfounded. Only a few dozen protesters turned out amid hundreds of thousands of cheering enthusiasts.

His repeated apologies for the crisis disarmed many critics. And the delicacy and erudition of his speech on the relationship between church and state, delivered to both houses of parliament in Westminster Hall, emphasised that religion need not be “a problem for legislators to solve, but a vital contributor to the national conversation”.

His intellectual contribution to the conversation between faith and politics was perhaps the great hallmark of his papacy. He produced a series of weighty encyclicals – on love, on hope and on social justice – which did not shy from engaging with political issues. But unlike previous popes, he also continued to publish personal writings, most notably a trilogy on the person of Jesus.

Yet his continuing insistence on adhering to his previous status was to cause great problems. He failed to understand that the kinds of things he had said as a professor, or even a cardinal theologian, could not continue unchanged once he was pope. That fact was rudely brought home to him when he went to his old university at Regensburg in 2006, the year after he became pope, to give a lecture on one of his favourite themes, the relationship between faith and reason.

In discussing defective understandings of rationality, the Pope quoted a 14th century Byzantine emperor’s remark that the only new things in Islam were “bad and inhumane such as [the Prophet Muhammad’s] command to spread by the sword the faith he preached”.

The remark provoked outrage throughout the Muslim world. It transpired that the pope had written his lecture without consulting Vatican experts on Islam. Benedict did learn from his mistakes, but PR blunders seemed to dog his steps. In 2009 he lifted the ban on the Society of St Pius X, an ultra-traditionalist group of followers of Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre who had broken away from the Church in 1988. But Benedict lifted the excommunication on key members of the group without checking on their record.

Within days it emerged that one of the renegade bishops, Richard Williamson, was not just not a schismatic but had been convicted and fined for denying there were gas chambers in Nazi Germany’s death camps in a 2008 interview with Swedish television carried out in Germany. The verdict was later upheld on appeal, with the fine reduced. In the end, Benedict’s negotiations to readmit the Lefebvrists to the mainstream Church foundered over their continued rejection of the Second Vatican Council.

Other papal banana skins followed. In 2009 he announced the establishment of a new Ordinariate to create a home within the Catholic Church for Anglicans disenchanted with the Church of England after women were admitted to the priesthood. He acted without consulting the Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, to whom he had been theologically close, and without asking the advice of the Catholic bishops of England and Wales.

And he issued the official constitution of the new body on the eve of Guy Fawkes day – a date that was spectacularly unhelpful for English bishops trying furiously to insist that the move would not damage Catholic-Anglican relations, which had previously been warming for decades. Critics were unclear whether Benedict’s Vatican was characterised more by incompetence or insensitivity. The blunders which followed offered contradictory indications.

The crisis over sex abuse by priests – and the repeated attempts to cover it up rather than address the problem – was perhaps the darkest shadow over Benedict’s papacy. The irony was that Benedict was much tougher, internally, on the problem than his predecessor had been. In 2001, Ratzinger persuaded John Paul II to place clerical sex abuse cases under his sole jurisdiction in the CDF. On his various travels, Benedict made a point of meeting, privately, the victims of priestly abuse and offering his personal apologies.

But some victim support groups condemned him for not handing guilty priests over to the police. In 2022, an independent report in Benedict’s native Germany alleged that he had failed to take action in four cases when he was Archbishop of Munich between 1977 and 1982. The frail former pope acknowledged in an emotional personal letter that errors had occurred and asked for forgiveness. His lawyers argued in a detailed rebuttal that he was not directly to blame.

Benedict’s scholarly temperament was ill-suited to handling such matters. Nor was governance his natural forte. The Vatican bureaucracy that had become dysfunctional towards the end of the papacy of John Paul II ran largely unchecked during the Ratzinger pontificate.

To cap it all came the Vatileaks scandal, which gathered steam in 2012. Someone inside the Vatican, close to the pope, had been leaking documents to an Italian journalist. Pieced together, they created a dossier that revealed a Vatican bureaucracy riven by intrigue and in-fighting, clericalism and careerism, ambition and arrogance.

Benedict was shaken to the core when he discovered that the leaks came from his butler, Paolo Gabrieli, a man whom he had trusted like a son. The pope would later set up a commission of three senior cardinals to investigate. Benedict’s personal solution to all this seemed to be only to withdraw into his scholarship. He spent more and more time in his study, with his books, cats and piano (playing Bach and Mozart) and writing the thoughtful documents of philosophical theology that may well prove to be his real legacy.

All this took a toll on him, emotionally and physically. In March 2012 on a trip to Mexico and Cuba, he lost his balance in his room and fell, hitting his head on a bathroom sink. The accident was not confirmed by the Vatican until later, but it would appear a key moment. When he returned from the gruelling trip, he is said to have spent many hours praying before the large bronze figure of Christ that looked down from the wall of his small private chapel in his apartments in the Apostolic Palace.

In long prayer, he decided to do something no pope had done for 598 years, since Pope Gregory XII in 1415 stepped down to end the Western Schism between rival popes and anti-popes. He would resign.

Another element that may have aided the decision was that on 17 December 2012 the three cardinals charged with investigating the Vatileaks affair reported back to him. Pope Benedict was horrified at what their report contained. He knew he did not have the energy or skills to tackle the problem.

But if the Vatican’s self-serving bureaucracy thought their entrenched resistance had defeated Benedict XVI they were wrong. The pope took the report and locked it in the papal safe to await the arrival of his successor. Then he went to the Vatican’s prison to visit his jailed butler and decreed that he should be released three days before Christmas.

On 11 February 2013 Pope Benedict XVI summoned a routine meeting of cardinals to announce the names of some new saints. He had written the 350-word statement himself, sending it only to a Latin expert in the Secretariat of State to make sure the grammar was correct.

The translator had been sworn to secrecy. Benedict read the words from the dead language in a weak but steady voice. To run the Church, he said, “both strength of mind and body are necessary, strength which in the last few months has deteriorated in me to the extent that I have had to recognise my incapacity to adequately fulfil the ministry entrusted to me”.

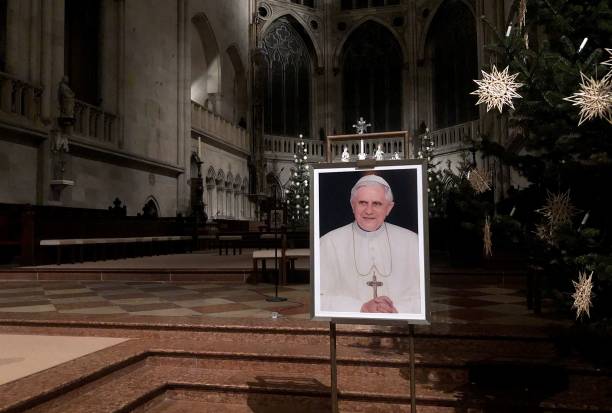

He would cease to be pope at 8pm on 28 February 2013, he announced, clearing the way for the election of a successor. It was the first papal resignation for six centuries. This deeply conservative man had produced an act of extraordinary imagination and considerable courage.

After his retirement, the relationship between Benedict and his more liberal successor – Pope Francis, who hails from Argentina – was, by definition, unusual. Although he promised to keep a low profile, Benedict wrote, gave interviews and, unwittingly or not, became a lightning rod for those conservatives who opposed Pope Francis. Confusion over the “two popes” was not aided by the fact that Benedict chose to continue wearing white and be known as Pope Emeritus – rather than returning to his birth name.

Whatever the difficulties around the “two popes”, Pope Francis was always generous in his public remarks about Benedict. Early this month, he said: “[It] is important to reaffirm that the contribution of his theological work and, more generally, of his thought continues to be fruitful and effective.”

However, it was his resignation – one of the most radical acts in the history of the 2,000-year papacy – for which Benedict will widely be remembered. Nothing in the Roman Catholic Church would ever be the same again.

Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI was born on 16 April 1927 in Marktl, Germany, as Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger, and died on 31 December 2022

Paul Vallely’s biography ‘Pope Francis – Untying the Knots: The Struggle for the Soul of Catholicism’ is published by Bloomsbury

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks