Pierre Paulin: Innovative designer who helped to revolutionise everyday furniture

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The French designer Pierre Paulin created eye-catching, convivial, comfortable chairs shaped like mushrooms, oysters, tongues and tulips, and attracted the patronage of presidents Georges Pompidou and François Mitterrand, who asked him to redecorate parts of the Elysée Palace in the Seventies and Eighties.

Built from metallic frames and rubber webbing padded with foam, and covered with stretchable material in a variety of bright colours, his simple, hard-wearing, affordable chairs, divans and sofas caught the mood of the freewheeling Sixties and sold in huge numbers. They became so iconic that they are now in the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris.

Of the four rooms that Paulin refurbished for Pompidou in 1971, only the sitting room decoration remains in situ, while the more traditional- looking furniture he created for Mitterrand's private office in 1984 has since been used by the French equivalent of the Lord Chancellor and the Minister for the Environment in recent years.

Acclaimed in Japan and the US, Paulin was less celebrated in France, possibly because of his association with the presidential office. However, over the last two years, he was the subject of several retrospective exhibitions, including a major one at the Gobelins in Paris entitled Pierre Paulin: Le Design Au Pouvoir ("design in charge"). The exhibition examined the designer's work for the Mobilier National, the atelier in charge of the creation and the preservation of furniture used in government buildings.

"I did my best to respond to the needs of the client in a style that was my own," he said of his presidential commissions. "When Pompidou first contacted me, I was working on swing doors for toilets. He was clearly making a political gesture. He wanted modernity to enter the homes and the mindset of the French.

"I got on best with Mme Pompidou," Paulin recalled. "I covered the original Napoleon III gilded wood panels with beige material and put an igloo shape inside one of the rooms." On the other hand, according to the designer, Mitterrand "needed a link with tradition."

Born in Paris in 1927, Paulin had a French father and a stern German-speaking Swiss mother. He grew up in Laon in the Picardie region of northern France, and greatly admired his uncle, Georges Paulin, who designed cars for Panhard, Peugeot and Rolls-Royce Bentley, patented the first power-operated retractable hardtop in 1931, and was a hero of the Resistance. He was executed by the Nazis in 1942.

Paulin failed his baccalauréat and trained as a ceramist in Vallauris on the French Riviera, and then as a stone-carver in Burgundy. An injury to his right arm in a fight put paid to his dreams of becoming a sculptor and he attended the Ecole Camondo in Paris, where later designers such as Philippe Starck also studied. He had a stint with the Gascoin company in Le Havre and developed a keen interest in Scandinavian and Japanese design as well as the functional furniture created by Charles and Ray Eames, Florence Knoll, Herman Miller and George Nelson in the US.

Paulin first exhibited at the Salon des Arts Ménagers in 1953, which lead to his work appearing on the cover of the magazine La Maison Française. The following year, while employed by the Thonet company, he began using swimwear material stretched over traditionally made chair frames. But he really found his forte when he joined the Maastricht-based Dutch manufacturers Artifort and came up with the Mushroom chair in 1960.

"It represented the first full expression of my abilities. I considered the manufacture of chairs to be rather primitive and I was trying to think up new processes," he said last year. "At Artifort, I started using new foam and rubber from Italy and a light metallic frame, combined with "stretch" material. Those new, rounder, more comfortable shapes were such a success that they're still being copied today. I have always considered design to be a mix of invention and industrial innovation."

However, when Paulin showed Artifort boss Harry Wagemans his "tongue" prototypes, the Dutchman was adamant that the model would never go into production. "I had tried to appeal to the lifestyle of young people. They were into low-level living," explained the designer. "Then, in 1968, Harry's son had a party with friends from all over Europe and they loved the chairs. When Harry popped in to see how they were getting on, he understood what I had been aiming at all along."

Paulin's mushroom, tongue and tulip chairs were runaway successes, admired for their clear lines, the sensual feel of their material or just simply for the way their shapes cradled the body. In 1969, he won a Chicago Design Award for his Ribbon Chair. By then, he was involved in the renovation of the Denon Wing of the Louvre Museum. In 1971, he redecorated the living, dining, smoking and exhibition rooms of the Elysée's private apartments for Pompidou.

After years with ADSA, the industrial design agency of his second wife Maia Wodzislawska, he launched his own consultancy in 1979 and worked for Calor, Ericsson, Renault, Saviem, Tefal, Thomson and Airbus.

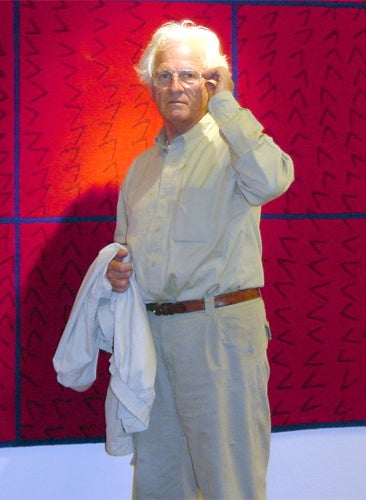

Tall, distinguished, and elegant with his silvery hair, Paulin saw himself as "un marginal", an outsider. He remained modest about his achievements and deplored the cult of the star designer. "Objects should remain anonymous," he argued. "It's extremely dangerous to give too much importance and status to people who are only doing their job. Working for the enjoyment of the greatest number is very gratifying, much more so than any official honour."

Paulin's forward-looking, innovative designs influenced many, including Olivier Mourgue, whose futuristic Djinn chairs featured in Stanley Kubrick's classic film 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Fifteen years ago, Paulin retired to the Cévennes in southern France but still came up with new designs, while several of his iconic chairs and sofas remain in production. Last year, an auction of 76 of his original pieces attracted many impressive bids.

Most of all, Paulin was an intuitive designer. "I had an uncanny ability to picture tri-dimensional objects. I could think up a shape and make it spin in my head like a sculptor or an architect would," he said. "I made the most of that gift."

Pierre Perrone

Pierre Paulin, designer: born Paris 9 July 1927; twice married (three children); died Montpellier 13 June 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments