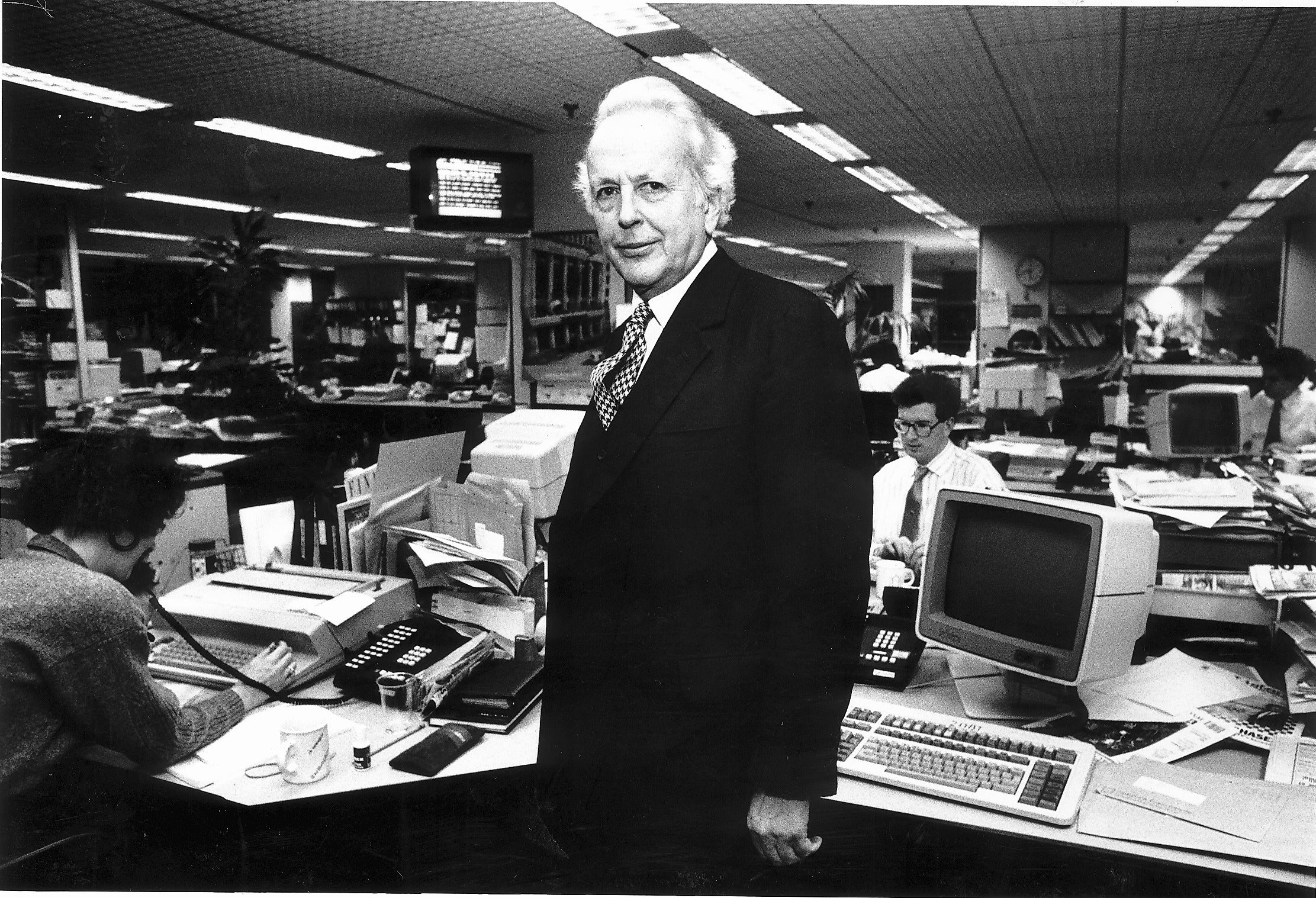

Peregrine Worsthorne: Contrarian columnist and former editor of The Sunday Telegraph

The journalist was a taunter of the left and a staunch defender of the ruling class

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Shortly after the Second World War, Peregrine Worsthorne was invited to a grand dinner party in the Scottish Highlands to meet Kurt Hahn of Gordonstoun School. This celebrated headmaster believed the purpose of education was to instil physical and moral courage. Worsthorne, then in his mid-twenties, stunned the table by informing Hahn that he was quite mistaken: it was more important to prepare the young for the moral murkiness, ambiguities and ironies of life. Hahn appeared amused, and interested. Worsthorne wrote later: “That evening was when I discovered the kicks to be got from going as near to the conversational precipice as dammit without falling over.”

It was the start of a career as an eminent contrarian. First as a columnist and then as editor of The Sunday Telegraph, Worsthorne taunted the left and encouraged the Conservative Party to remain loyal to the concept of a ruling class. He could be naive, sometimes charming, and often funny, particularly when he took to the road. He wrote memorable accounts of journeys to California, Scotland and Australia, which were collected in an amusing book titled Peregrinations; Alan Watkins said fondly that on his travels Worsthorne appeared to be a combination of Lord Curzon and Mr Pooter.

His political impact was occasionally blunted by indiscretions and transgressions. He toppled over the precipice when a television interviewer asked what he thought about the shaming of Lord Lambton, a junior minister who had been discovered in bed with two prostitutes. Worsthorne replied that he thought the public wouldn’t a give a f***. It was only the second time the F-word had been used on British television. He thought the incident delayed his promotion. He was the most readable of the right-wing political columnists, and his enthusiasm for Margaret Thatcher was rewarded with a knighthood in 1991.

Worsthorne admits in an artlessly indiscreet autobiography titled Tricks of Memory that his mother had written that he was nearly always an antagonistic child, even at the breast. He was born in Cadogan Square in Chelsea in 1923, the son of a Belgian man-about-town named Koch de Gooreynd, who had changed his name to Worsthorne, a small village in Lancashire. Peregrine spent school holidays there, effectively as a ward of James, the butler. He never got to know his father, who was summarily dismissed from his mother’s presence shortly after his birth. Her second marriage was to Montagu Norman, the governor of the Bank of England. Among Worsthorne’s early memories is of being shouted at by Winston Churchill because he had been shown to a room with an unmade bed, and of learning from an American named Herbert Hoover that, though Worsthorne lived in the Red House, his own home was the White House.

He was sent to school at Stowe, where he behaved like a snob and posed as a Roman Catholic bigot. He confessed that, had he gone to a Catholic school, he might well have championed Protestantism. He was also seduced on a sofa by George Melly, the entertainer. Not long after leaving school for Cambridge University, he began to lose his religious ardour and discovered girls. His war was spent in Phantom, an intelligence unit advancing into Germany. Worsthorne was recruited, like a character in Evelyn Waugh’s War Trilogy, at the bar of White’s Club. He said that war sorted out the men from the boys and that he himself had not yet discovered into which category he fell.

He was not so lucky when he started in journalism. The editor of the Glasgow Herald offered him the job of sub-editor – Worsthorne thought this meant deputy editor. When he turned up at the Herald’s office in Buchanan Street, he was directed to the sub-editors’ room and told to make the f***in’ tea. That was how he was remembered after two unproductive years in Glasgow.

His first proper job was at The Times, where he felt he belonged. He was sent to Washington DC as deputy to The Times’s correspondent. Worsthorne took the Republican Party seriously. In 1952, when most of his colleagues were dazzled by the intelligent liberalism of Adlai Stevenson, Worsthorne accurately forecast a win for Dwight Eisenhower. He also had sympathetic words to say about Senator Joe McCarthy. He thought that Westminster could also benefit from a dose of anti-communism.

The editor of The Times, Sir William Haley, was unsympathetic, however, and Worsthorne’s punishment was to be frozen out as the correspondent in Ottawa. The hint was broad enough to persuade Worsthorne to join The Daily Telegraph in 1953, when it was unapologetically the “Torygraph”. He became editor of The Sunday Telegraph when the papers were purchased by Conrad Black in 1986.

Anti-communism was more welcome at the Telegraph and Worsthorne expanded his field of fire, writing long articles in Encounter magazine and establishing a reputation as an ardent Cold Warrior. In domestic politics, he was a disciple of the philosopher Michael Oakeshott. Worsthorne and friends such as Henry Fairlie, George Gale, Paul Johnson and Kingsley Amis formed a circle bound together by a liking for politics and parties, and they infiltrated newspapers and magazines with unpredictable, usually right wing, ideas that had been largely dormant since 1945.

They were contemptuous of Labour’s left, which they thought was still in thrall to the Soviet Union, but they were also critical of the comfortable consensus politics of the Fifties and early Sixties. Fairlie had revived the idea of the Establishment to describe conspiracies of silence, such as the lengthy cover-up about the damage done to MI6 by Philby, Burgess and MacLean.

When The Sunday Telegraph was launched in 1961, Worsthorne wrote the principal article on the leader page. He believed his role was to confront received opinion, think the unthinkable and point out unacceptable consequences of actions which were, on the face of it, desirable. This led him up some strange byways. He declared himself sympathetic to the death penalty and praised the legacy of British colonialism. He was regarded as a bit of a joke by the left, but he gave the more radical Conservatives a voice. He could certainly argue that right-wing policies were more widely appreciated at the end of his career than at the beginning, and could claim some of the credit. Although he never warmed to Edward Heath, he was a fan of Margaret Thatcher, who would have liked his politics and his “sub-Byronic good looks” (his phrase).

His sacking as The Sunday Telegraph’s editor during breakfast at Claridges did not stop him, he said, enjoying his favourite perfectly poached eggs on toast. As consolation, he stayed on to edit the editorial pages, which were known as Worsthorne College, and specialised in spiteful profiles of establishment figures such as Lady Elspeth Howe and John Julius Norwich. He retired from the paper in 1991.

Worsthorne admitted to intellectual and social snobbery. Close colleagues found this entertaining, but it was not always popular among the rank and file in the Telegraph’s newsroom. “You’re nothing but a tinsel king on a cardboard throne,” he was told one evening by a drunken colleague in the Falstaff pub. This hurt, and it is not to be found in his autobiography, though he did not flinch from recalling other acutely embarrassing sexual episodes.

In Hamburg at the end of the war, he was being entertained by a baroness – officially she was supposed to teach him German – when her injured husband, returning unannounced from the eastern front knocked at the door. “Don’t let him in,” she said, “he’ll kill me.” Worsthorne drew his service revolver and the German officer retreated. “A horrible story,” he admitted.

In retirement he wrote a book called In Defence of Aristocracy. He left London to live in the country with his second wife, the television journalist Lady Lucinda Lambton, the daughter of a viscount.

Sir Peregrine Worsthorne, journalist, born 22 December 1923, died 4 October 2020

Stephen Fay died on 12 May 2020

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments