Paulita Sedgwick: Rancher, actress and independent film-maker

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.But for some worn planking, Paulita Sedgwick's name as a film-maker might have been better known. In the early 1990s, Sedgwick sailed up the Rio Negro in Brazil to make a short epic called Avon Ladies of the Amazon. (She had earlier discovered that the intrepid cosmetics sellers include Amazonia on their beat. "People think Indians only want guns and knives," said Sedgwick, sagely. "Girl Indians want lipstick.") Having hired a boat and a camera crew, she had all but finished the movie when she suggested that the cameraman walk out on to a jetty to film the final scene. With a groan, the structure collapsed, plunging him and his camera into piranha-infested waters. The cameraman was pulled from these; the camera, its video cassette containing the entire movie, was not. "That," said Sedgwick, with clipped New England stoicism, "was a sad thing".

This story was variously typical of her. For all its amusement value, Avon Ladies of the Amazon was a study of the exploitation of a poor culture by a rich one. (Her last film, Las Vacaciones de Lalinde Schmidt, reset this story in post-recession Buenos Aires.) Sedgwick herself had every reason to sympathise with the rich, being one of them herself and coming from the bluest of American bloodlines. Her ancestor, Robert Sedgwick, was Major General of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. (Asked whether he had sailed to America on the Mayflower, Sedgwick, shocked, said "Certainly not. The Mayflower was full of servants. We were on the Arabella.") Her grandfather, Ellery, proprietor of the Atlantic Monthly, was the first person to publish Hemingway; her father, Cabot, was a diplomat.

But Sedgwick herself had more in common with two other of her relations. Theodore Sedgwick – buried, like two centuries of the family, in the circular "Sedgwick Pie" cemetery in Stockbridge, Massachusetts – was an early justice of the Supreme Court and the first to plead for the freedom of an escaped woman slave, Mum Bett. (She, too, is buried in the Pie.) And Edie Sedgwick, a cousin and Warhol girl, also made a career in film, albeit more tragically.

Paulita Sedgwick was born during the Second World War in Washington DC, her upbringing in Haiti, Japan and, finally, in Spain, a mixture of corps diplomatique propriety and bohemian licence. This was reflected in her adult character. Her Spanish accent, like her American one, was that of a pre-war ruling class, although she got in trouble at the University of Madrid for associating with anti-Franco classmates. If Sedgwick's acquaintances tended to the raffish – close friends included transvestites, tattooists and a sprinkling of ex-rent boys – she was also a regular in the Royal Enclosure at Ascot. Dressed otherwise unvaryingly in black Vivienne Westwood jeans and 18-hole Doc Martens, she had the courtliness of another time: a cup of tea at a friend's house would result, the next day, in a hand-written note remarking on its deliciousness.

After training at the Webber Douglas drama school in London in the early Sixties, Sedgwick pursued a decade-long career in off-off-off-Broadway plays. (It was during one of these that she met her cousin Edie's svengali, Andy Warhol. "In 20 minutes, I told him everything I knew," she recalled. "He said three words: 'uh-huh', 'uh-uh' and 'maybe'.") In 1971 she crashed a party in New York given by the film-makers Merchant/Ivory. Chatting to a young man hiding, like her, behind a pillar, she confided that she was only there because she wanted a part in the pair's second film, Savages. "My name is Ismail Merchant," he replied good-naturedly. "Which part would you like?" Sedgwick played Penelope, "a high-strung girl", and later Esther in the Merchant-Ivory film of Jean Rhys's Quartet.

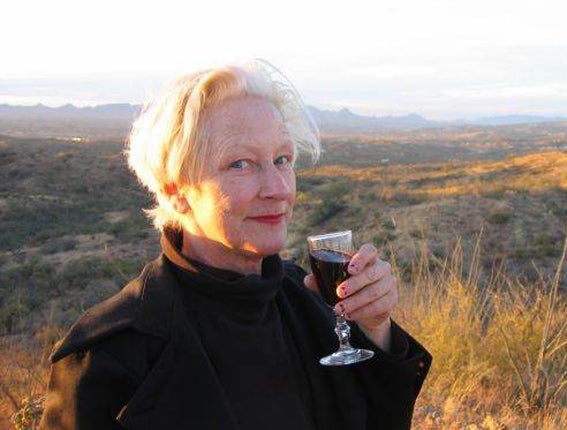

After the birth of her son, Angel – the only name she could think of that was spelt the same way in Spanish and English – Sedgwick began to divide her time between America, Paris and London and to make films as well as act in them. Among these was Blackout (1994), a feature-length drama set in post-apocalypse Westminster and starring the ex-Warhol superstar and latter-day Mormon, Ultra Violet. Ultra Violet plays the part of Arlette, the inventor of a miracle blusher called Eternacream: as in the lost Avon Ladies of the Amazon, the film draws a clear (and unexpectedly puritanical) line between immorality and make-up. Apart from colouring her hair white and lips red, Sedgwick herself avoided cosmetics. With her perennially black outfit and ice-blue eyes, she was a striking enough figure without them.

Her style and good manners survived a long battle with cancer. Discovering a tumour in her breast in 1987, doctors gave Sedgwick two weeks to live. Characteristically refusing to succumb, she survived for 22 years, fighting off malignancies in her womb, kidneys and, latterly, lungs and brain. Through all of this, she remained good humoured and devoid of self-pity.

The advertising woman, Fay Jenkins (Independent obituaries, 5 February 2005), a fellow cancer patient, was visited by Sedgwick through a mutual friend in the clinic where both were being treated. Rocking with laughter, Jenkins recalled her visitor's advice: "She told me on no account to have chemotherapy," she said, "because it would change my silhouette and force me to buy a whole new wardrobe."

On her father's death in 2003, Sedgwick inherited the house on the family's Santa Fe ranch, now run as a charitable trust, near Nogales on the Arizonan border with Mexico. Quietly religious, she had an adobe chapel built to her parents' memory, and imported a buffalo to which, when it seemed depressed, she would play classical music. (It died.) "There is," she said, "always time for beauty," and she found it at last in the one place she had come to call home.

Charles Darwent

Paulita Sedgwick, independent film-maker and rancher: born Washington DC 7 December 1943; one son; died Arizona 18 December 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments