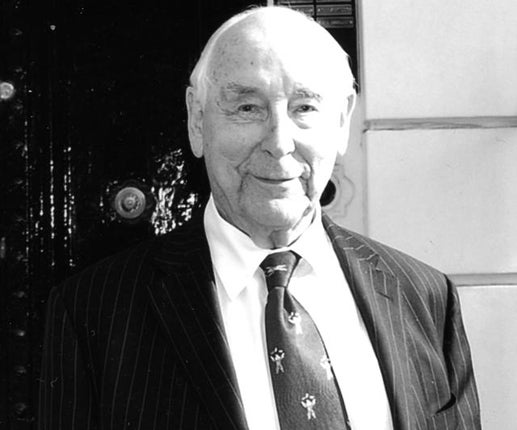

Paul Sherwood: Pioneering anaesthetist and physician who developed the Sherwood Technique for the relief of back pain

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The eminent Harley Street physician Paul Sherwood has died at the age of 93. From his early beginnings as an anaesthetist, it was his lifelong work dedicated to non-specific back pain that earned him the reputation as a pioneer in this field.

Some 60 years ago Sherwood started to develop the treatment that would become the Sherwood Technique, a holistic procedure which involves looking beyond the actual attack of pain to the origin of the problem, treating the underlying cause and thereby bringing long-term relief. It has come to be regarded as the most effective method of treating non-specific back pain.

The Sherwood Technique is now used by practitioners all over the world. Sherwood's success in treating back problems (and some of the associated conditions) brought him patients from far and wide, including politicians, sports personalities, actors and heads of state. Some people went to extreme lengths to consult him. The film director Fred Zinnemann, for example, wanted to be treated by Sherwood but felt he couldn't take several months off to be in London for the treatment. His solution was to make a film in Britain; that film turned out to be the award-winning A Man for All Seasons.

Paul Sherwood was born in Winchmore Hill, London. He survived an early brush with death when, having been left outside in his pram to get some fresh air, a German zeppelin in difficulties dropped its anchor, smashing through his pram. His mother and nanny rushed out expecting the worst, only to find Sherwood amongst the rhododendrons, none the worse for his ordeal.

Sherwood was educated at Epsom and studied medicine at Queens' College, Cambridge and the Westminster Hospital. He subsequently went to Barts, where he was the first ever non-Barts trained doctor on the staff. His father, Martin, was a society doctor, and it was said at the time that "anybody who was anybody" went to Martin Sherwood. The Sherwood home was a glamorous environment; Martin frequently invited well-known people in society as house guests. The Kings and Queens of Greece and Spain were regular visitors, as were the Bentley Boys.

Paul Sherwood was a man ahead of his time. His use of blood transfusion revolutionised surgery. As an anaesthetist, he measured the amount of blood loss in his patients, realising that to expedite a speedy recovery, the patient needed the same amount of blood put back in. Initially, though, he met with much resistance as the medical establishment insisted that putting more than a small amount of blood back in would kill the patient, despite the evidence of his much fitter patients!

Sherwood was on the team working to develop the first heart transplant operation in the UK, his job being to develop the necessary new anaesthesia techniques. Christiaan Barnard came over to observe the team's progress and then subsequently performed the first heart transplant in South Africa in 1967.

During the Second World War, Sherwood became anaesthetist for the two main pioneers of plastic reconstructive surgery, Sir Rainsford Mowlem and Sir Archibald McIndoe. While they developed the new surgery, he developed the anaesthesia to accommodate their new techniques. This included working with the "Guinea Pig Club", whose members were airmen who had been shot down and badly burned. The treatment of burns by surgery was in its infancy. Before that time, many severely burned casualties would not have survived. Sherwood, as anaesthetist, had to develop alternative sedation that didn't involve covering the face. This led to the beginning of modern anaesthesia.

During the war, Sherwood was sent over to Russia to train their doctors on how to improve their hospitals. Once, when staying in a hotel in Moscow, Sherwood awoke in the middle of the night to find two Russians standing over him with Sten guns. Sherwood grabbed one of the guns and shouted at the Russians to get out. Out of shock, they obeyed!

Towards the end of the war, Sherwood, another doctor and a dentist were made honorary members of a commando unit and operated a field hospital behind enemy lines in Yugoslavia for the commandos and Yugoslav partisans. The team were presented to President Tito, who wanted to confer a medal on them, but the British Government turned this down on the grounds that it was not their policy to accept a decoration from a communist power!

After the war, Sherwood wanted to make his own way home to Britain, so he sought the commanding officer's permission. To his surprise, permission was granted on the condition that Sherwood took with him the commanding officer's secretary, who had requested to do the same. After making the long journey to France, their money had run out. Having explained their predicament to his companion, she exclaimed: "Well, if things are that bad I will just call daddy and get him to send a plane!" It turned out her father was Sir Frank Spriggs, executive chairman of the Hawker Siddeley Aircraft Company. The plane was duly sent and they arrived safely home in Britain and as reward for bringing his daughter home, Sherwood was given the option to buy one of the first post war cars produced, an Armstrong Siddeley Hurricane.

It was in the 1950s that Sherwood first turned his interest to the treatment of non-specific back pain. He continued to work from his Harley Street practice right up until the moment he suffered a severe stroke in 2009, from which he never fully recovered. Sherwood wrote five books on The Sherwood Technique, including his bestselling book The Back and Beyond, later republished as Your Back, Your Health.

Sherwood's interests included a passion for music, opera and ballet, but also extended to cars and motor sport. He was a stalwart with his son Robin of the Motor Sports Association's Euroclassic rally, annually taking part in this 2000-mile event across Europe right up to the age of 92.

Paul Sherwood, physician and author: born London 15 November 1916; married twice (two sons, one daughter); died Watford 31 October 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments