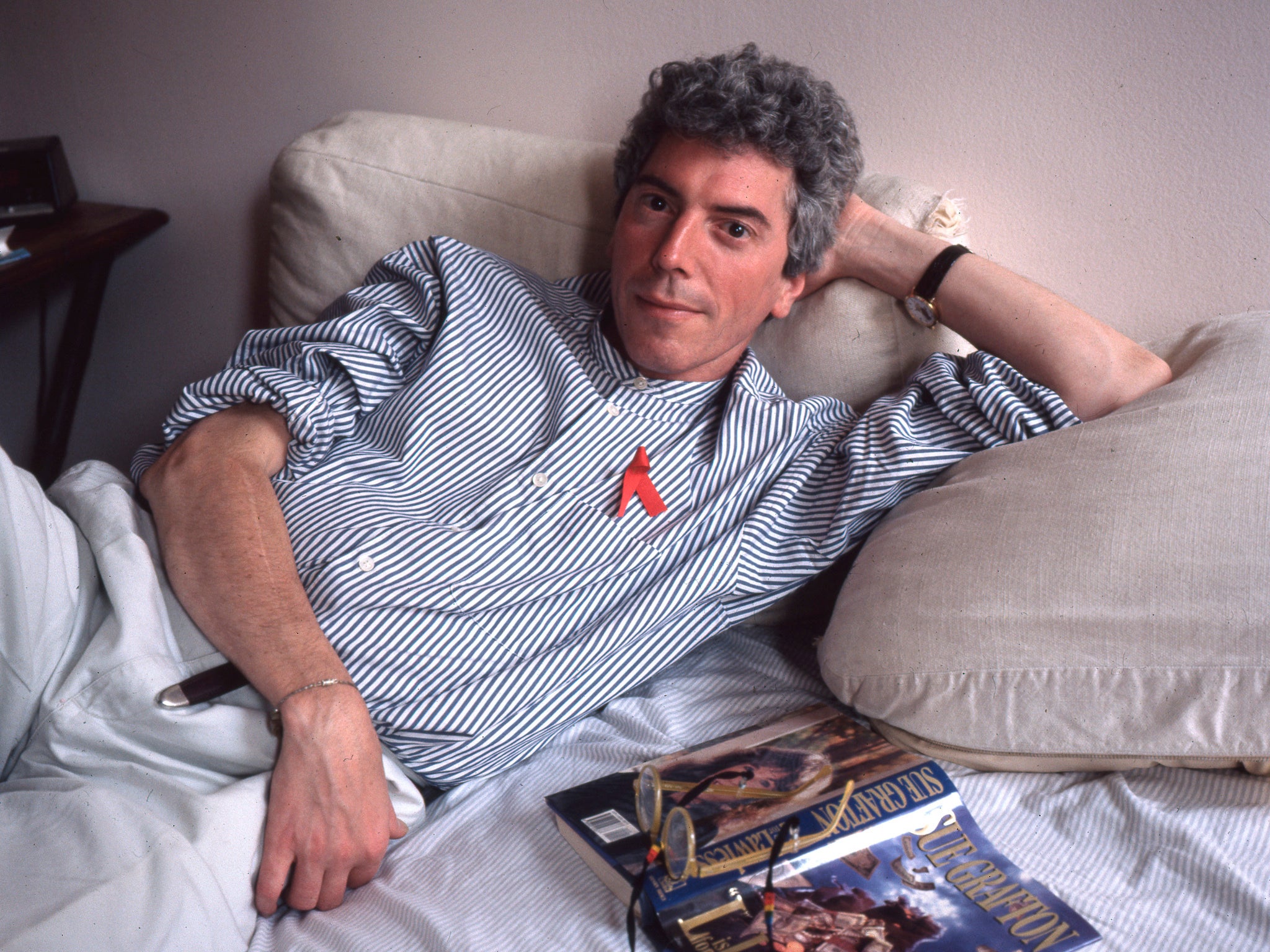

Patrick O’Connell: Aids campaigner behind the symbolic red ribbon

The activist used his experience in the arts community to create awareness of the epidemic and end stigma towards the gay community

Patrick O’Connell was a member of the New York arts community who responded to the Aids crisis of the 1980s by forming an awareness group and launching the red ribbon, which became a symbol of support for those hit by the epidemic.

Its colour represented blood and the sparse design alluded to the initial silence surrounding the disease.

O’Connell, who has died aged 67 of complications from Aids after almost 40 years of living with it, was attending the funerals of victims almost every month while politicians and the general public seemed ignorant of the crisis – or indifferent to what some referred to as the “gay plague”.

Arts organisations in New York, which had become the Aids capital of the US, were already mounting campaigns to tackle this when, in 1988, O’Connell – who had been diagnosed with HIV – started monthly meetings with friends in a loft in Manhattan’s Chelsea district.

It became the headquarters of their group, launched the following year as Visual Aids with an initiative titled Day Without Art, when galleries and museums covered their exhibits to represent human loss.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art replaced a Picasso painting with a sombre placard containing information about Aids and this national day of mourning became an annual event.

Others followed, such as Night Without Light in 1990, when New York’s skyline went dark for 15 minutes.

The following year, O’Connell and his fellow campaigners launched the Red Ribbon Project in an effort to remove the stigma surrounding Aids. Fifteen of them cut and folded 3,000 fine-quality ribbons, and stitched gold safety pins to the backs, before distributing them around the city for people to wear.

Realising the enormous PR potential, they also had the ambition of featuring the inverted V-shape symbols of awareness at the annual Tony Awards ceremony – honouring the best in New York theatre – two weeks later.

O’Connell and his colleagues hit the phones, speaking to actors, costume designers, hairdressers and other Broadway contacts. On the night, ribbons were placed on seats at the Minskoff Theatre before host Jeremy Irons stepped onto the stage wearing one in his lapel. Scores of other actors present did the same.

At the following year’s Oscar awards, ribbons appeared on hundreds of celebrities, including a satin one that outshone the chandelier earrings and diamond ring worn by Elizabeth Taylor, who was already an active Aids campaigner following the death of her friend Rock Hudson from the disease.

Soon, these small spots of colour were flapping in the wind as people wore them on streets across the US – and around the world. A British version was donned by many of those filling Wembley Stadium in 1992 for a Freddie Mercury tribute concert in memory of the Queen singer who died of Aids. A year later, the US Postal Service issued a red-ribbon stamp.

Some campaigners derided the initiative as hollow, but O’Connell regarded it as creating an impact where before there had been almost none.

“People want to say something, not necessarily with anger and confrontation all the time,” he said. “This allows them – and, even if it is only an easy first step, that's great with me. It won't be their last.”

O’Connell’s own health deteriorated and, in 1995, he stepped down as the founding director of Visual Aids, which had progressed from voluntary group to non-profit organisation.

“I am almost stripped and bereft of contemporaries who remember me as young and cute and vibrant,” he said at the time.

Patrick James O’Connell was born in Manhattan in 1953 to Helen (nee Barry), a secretary, and Daniel O’Connell, a wire lather and ironworker. He studied at Fordham Preparatory School before graduating in history from Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1975.

After launching a career in the arts, he became director of Hallwalls Contemporary Arts Centre, in Buffalo, upstate New York (1977-78), but left after a year to return to his home city to work for Artists Space, a gallery for up-and-coming painters and photographers.

At around this time, O’Connell was the victim of an anti-gay hate crime when he was attacked by a group of teenagers. It left a permanent foot-long scar on his arm, which needed skin grafts. He also had to contend with alcoholism but finally put it behind him by entering rehab.

An adviser to the National Endowment for the Arts Aids Working Group, he lived the final years of his life on disability benefits in a small New York flat.

Visual Aids continues to use art to promote awareness and support artists suffering from Aids and HIV.

O’Connell’s long-time partner, James Morrow, died of cancer in 2000. He is survived by his brother, Barry.

Patrick O’Connell, arts administrator and Aids campaigner, born 12 April 1953, died 23 March 2021