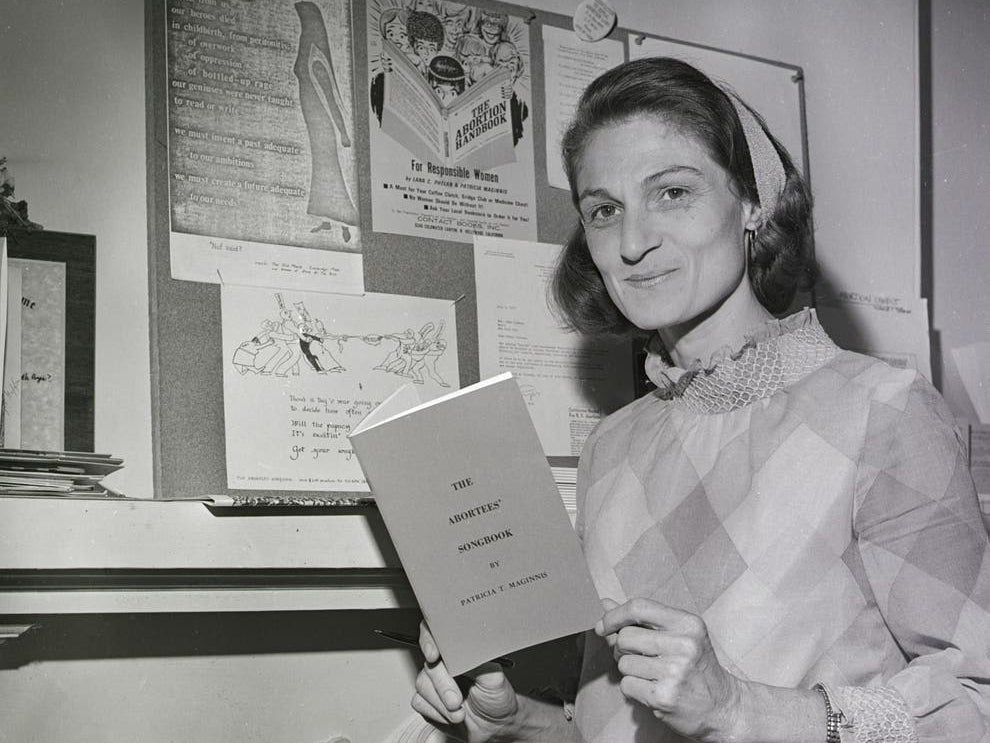

Patricia Maginnis: Pioneering abortion activist who fought for the right to choose

Maginnis was a voice for anguished women who, like her, had struggled to safely end pregnancies

In the decade before Roe v Wade legalised abortion nationwide, Patricia Maginnis emerged as one of America’s first abortion rights activists, campaigning on behalf of women’s freedom to safely end unwanted pregnancies.

She distributed a list of reliable abortion providers in Mexico, Sweden and Japan, organised medical conferences in which doctors shared safe abortion techniques, and even taught women how to perform the procedure themselves, sometimes delivering lectures while using an intrauterine device as a pointer.

Maginnis was a voice for anguished women who, like her, had struggled to safely end pregnancies and were sometimes hospitalised after botched procedures. While distributing pamphlets in 1966 that described two techniques for do-it-yourself abortions, she told reporters in San Francisco that she was “attempting to show women an alternative to knitting needles, coat hangers and household cleaning agents”.

The crusading activist, who helped thousands of women get abortions when the procedure was still illegal in most states, has died aged 93.

Maginnis died two days before a Texas law went into effect prohibiting most abortions, banning the procedure as early as six weeks into pregnancy. “Her activism reminds us that each of us can – and must – act so we can realise a future where reproductive freedom is truly a reality for us all,” said Kristin Ford, a spokesperson for Naral Pro-Choice America, one of the country’s oldest abortion rights advocacy groups.

The organisation traces its roots back to the work of Maginnis, who in 1962 started the Citizens Committee for Humane Abortion Laws, which became known as the Society for Humane Abortion and operated out of her apartment in San Francisco. Within a few years, she and her colleagues Rowena Gurner and Lana Phelan Kahn founded a sister group, the Association to Repeal Abortion Laws (Aral), a precursor to Naral.

“Maginnis helped to fundamentally reshape the abortion debate into the terms we're still using today,” journalist Lili Loofbourow wrote in a 2018 Slate article that helped introduce Maginnis to younger generations. “She was the first to take a passionate, public stance arguing that the medical stranglehold over women’s reproductive lives was corrosive. And the Society for Humane Abortion was arguably the very first American organisation to advocate a pro-choice position that centred on the woman, instead of the legal dilemmas of the physician – specifically, her right to privacy and choice.”

With Gurner and Kahn, Maginnis formed an activist team that became known as the “Army of Three”. They expanded their campaign from California to the rest of the country, meeting with women in private homes, granges, union halls and churches, where they taught audiences how to perform safe abortions, how to deal with police questioning and how to find doctors who could perform the procedure.

By the end of the 1960s, they claimed to have helped 12,000 women get out of the country to obtain safe abortions, running what was sometimes described as an “underground railroad”.

“Some leading obstetricians say privately that when they feel they must refuse to abort a patient, they usually send her to Miss Maginnis,” The New York Times reported in 1968. The newspaper had previously described her as a “38-year-old spinster” and “a slender, intense woman with the eyes of a zealot”. Alternative weeklies dubbed her the “Che Guevara of abortion reformers”.

Raised in a strict Catholic family in rural Oklahoma, Maginnis said she turned towards activism after years of being “in a constant rage”, angered by the lack of control women and girls had over their reproductive lives. Friends said that she combined righteous anger with a gentle, soft-spoken approach to campaigning, never raising her voice while handing out fliers or discussing abortion with strangers.

At the time, even talking about abortion was considered revolutionary. “The word ‘abortion’ was taboo,” Maginnis told Slate. “And I thought: That’s crazy. People won't talk about abortion! They’re afraid to. I’m going to talk about abortion! ABORTION!” She invited the police to her public appearances and classes, seeking arrest in an attempt to test the constitutionality of anti-abortion laws that banned distributing information about the procedure.

Authorities seemed hesitant to grant Maginnis further publicity. After she mailed a list of Mexican abortion providers to California attorney general Thomas C Lynch, violating postal laws, he responded only by notifying her that he was sending the list to the Board of Medical Examiners, according to The Times.

Nonetheless, she was arrested several times for her activism, including after distributing her DIY-abortion leaflets in 1966. The case against her was thrown out after a San Francisco law was declared unconstitutional. The next year, she and Gurner were arrested after arranging to teach an abortion class in San Mateo, under a California law that made it illegal to advertise abortion. That conviction was overturned in 1973, after a state appeals court declared the law unconstitutional.

Earlier that year, the Supreme Court delivered its ruling in Roe v Wade, establishing a constitutional right to abortion. Maginnis celebrated the decision, but even then she was concerned “that it wasn't codified into law”, said her friend Laurie O’Connell, an abortion rights activist who serves on the board of the Northstate Women’s Health Network in California.

“She knew it was fragile, and she still advocated for making it the law of the land and having no restrictions whatsoever,” O’Connell said. “That was her motive force, that women deserved abortion without restriction and without apology.”

“Otherwise,” she continued, borrowing language from Maginnis, “we were just ‘breeding chattel’.”

Patricia Therese Maginnis was born on 9 June 1928, in New York, where her father was studying veterinary medicine at Cornell University. His work took the family to Okarche, a small town outside Oklahoma City, where Maginnis grew up with six siblings during the Depression and Dust Bowl.

She told Slate that her father was “forever tortured because he had been conceived out of wedlock” and that her mother was racked by physical pain related to childbirth. “My mother would tell you she enjoyed having children,” she said. “I didn't go through childhood with that impression.”

After graduating from high school, Maginnis joined the Women's Army Corps, training as a surgical technician. After she was seen walking with a black soldier at Fort Bragg in North Carolina, she was reprimanded by a captain who accused her of “setting a bad example for young white women who might join the military”.

As punishment, she was assigned to a paediatrics and obstetrics ward in Panama, where she later recalled her horror at seeing women who were treated for botched abortions, were forced to give birth or had infants with major birth defects.

She later studied at San Jose State College, now a university, where she became pregnant for the first time. She got an abortion in Mexico and vowed never again to leave the country for medical care. When she became pregnant two more times, she performed two self-induced abortions; one required follow-up treatment in the hospital, where she was questioned by police in 1959, according to the Los Angeles Free Press. Asked whether she had given herself an abortion, she replied: “Sure I did. Want me to demonstrate how in court?”

Maginnis supported herself as a medical technician and a model, posing for painters and fine-art photographers until her early eighties. She funnelled the proceeds into refurbishing her house in Oakland, where she spent a year single-handedly digging out the foundation with a large serving spoon, her family said. She was similarly self-reliant when it came to clothes, picking up discarded garments on the street and putting them on after a wash.

Survivors include two sisters and two brothers.

In the decades after Roe, Maginnis broadened her activism to campaign on behalf of gay rights, animal rights and environmental issues, among other causes. She made pea soup for “Occupy Oakland” activists in 2011 and drew thousands of political cartoons, often accompanied by bawdy limericks, that she distributed at protests and rallies.

One of her best-known cartoons illustrated the challenges pregnant women faced in obtaining an abortion even after Roe. It showed a woman pleading before two doctors and a cigar-smoking politician. “Please,” she asks, “may I have a US Supreme-Court-approved politician-sanctioned psychiatrist-rubber-stamped clergy-counselled residency-investigated committee-inspected therapeuticked, US Health-Dept-statistised contraceptive-failure religious-sect-guilt-surmounted abortion.”

Pat Maginnis, activist, born 9 June 1928, died 30 August 2021

© The Washington Post

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks