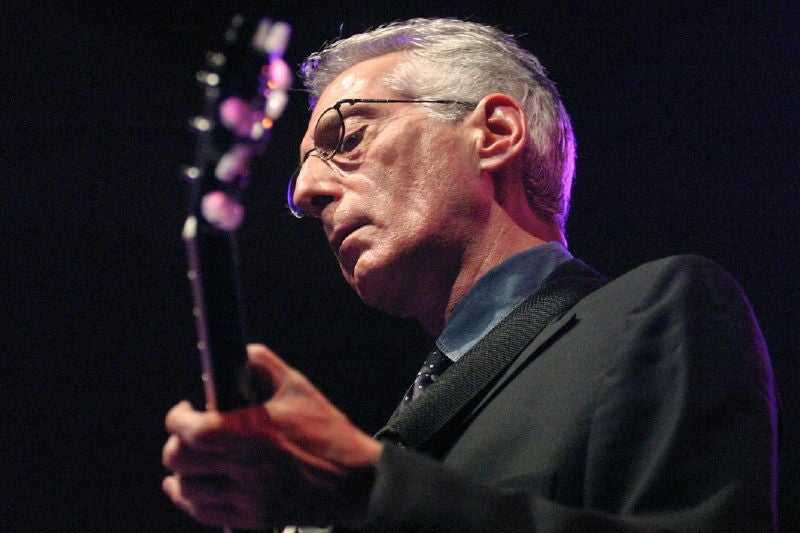

Pat Martino: One of jazz music’s finest guitarists

After suffering a near-fatal brain aneurysm in 1980, Martino managed to master his instrument for a second time

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.By the age of 35, when Pat Martino learned that he might have only a few hours to live, he was already considered one of jazz music’s finest guitarists. He had developed a sleek and fluid style modelled after guitarist Wes Montgomery, having begun touring as a teenager, and became known for his bracing lines, freewheeling harmonies, and dexterity on the fretboard.

But as Martino recorded his first dozen albums, veering from hard bop into soul, blues and eastern music, he also began experiencing mysterious headaches and seizures. When he suffered a near-fatal brain aneurysm in 1980, doctors finally diagnosed what was wrong, locating a tangle of veins and arteries that had impaired blood flow in his brain.

Told that he needed immediate surgery, he flew from Los Angeles to his home town of Philadelphia, where surgeons removed a blood clot as well as a portion of his left temporal lobe. He woke up in a cloud – he felt as if he had been “dropped cold, empty, neutral, cleansed”, as he later put it – with retrograde amnesia. He barely recognised his parents, and had no memory of his name, let alone his musical career.

“I had no interest in music,” Martino recalled, “no muscle memory of playing the guitar.”

But while listening to records and hearing friends play the instrument, he slowly began to play again, leading to an astonishing second act in which he recorded albums that rivalled his old records in elegance and creativity. He remained a vibrant force in jazz, even as he faced persistent health issues, continuing to perform until a lung condition forced him to retire in 2018.

“Every time you thought he was out, he’d come back,” his manager, Joseph Donofrio, said. “He was ferocious in his music and his integrity. It was only about his music, about his guitar, about his legacy.”

Martino was 77 when he died on Monday, at the same rowhouse in Philadelphia where he had spent part of his childhood.

From his early years as a bandleader, Martino had sought to push his sound in adventurous new directions, moving from organ-tinged jazz soul into psychedelic fusion. His fourth album, Baiyina (The Clear Evidence), included Indian instruments such as the tamboura and tabla, and was subtitled “A psychedelic excursion through the magical mysteries of the Koran”.

Martino later released an instrumental version of the pop song “Sunny”, which became a staple of his live shows, and showed a tender side on albums such as We’ll Be Together Again (1976), a collection of duets with pianist Gil Goldstein that included a rendition of Stephen Sondheim’s “Send in the Clowns”.

He received four Grammy nominations, including for the 2003 album Think Tank, recorded with celebrated musicians such as pianist Gonzalo Rubalcaba, saxophonist Joe Lovano, bassist Christian McBride and drummer Lewis Nash. “He has created his own language on the guitar,” banjo player Bela Fleck wrote in the liner notes. “He walks among us but down different pathways.”

Martino seemed to draw such acclaim in part because he built on bebop tradition while also tweaking conventions. “He starts a line on an unexpected beat, breaks his runs up to insist on a single note or riff, inserts odd-length leaps into standard licks and shifts accents around the beat,” New York Times music critic Jon Pareles once wrote. “His playing is articulately wayward, approaching tunes from odd angles and taking rewarding tangents; he makes song forms seem slippery and mysterious.”

After Martino’s brain surgery, his willingness to experiment only seemed to increase. He studied world music, drawing inspiration from Chinese and Japanese scales, and tinkered with digital tools, using an electronic orchestra to create lush pieces backed by pianos, strings and timpani – irritating his long-time record label, Muse, when he declined to include a guitar.

Martino professed not to care. “So many things have vapourised in my life,” he told The New York Times in 1995, “that I ask, ‘What am I alive for?’ I don’t need to be competitive. I’ve reached a point where I’m looking for no pedestal other than the ground I walk on.”

Patrick Carmen Azzara was born in Philadelphia on 25 August 1944. His mother was a homemaker, and his father was a tailor who sang at local clubs – using the stage name Martino, which spurred his son to do the same – and who briefly took guitar lessons from jazz legend Eddie Lang.

As Martino told it, his father lured him into music using a bit of reverse psychology, forbidding him to touch a guitar stored under the bed. He began playing at the age of 12 and, as he told it, launched a career in music aiming to make his father proud.

Dropping out of school at 15, he went on tour with R&B singer Lloyd Price and moved to Harlem, immersing himself in the neighbourhood’s soul jazz scene. He played with saxophonist Willis “Gator” Jackson, replaced George Benson in organist Jack McDuff’s band, and recorded his debut album, El Hombre (1967), at the age of 22.

Within a decade he was suffering from severe seizures, notably during a performance before a crowd of more than 200,000 people at the Riviera jazz festival in France. He took a break from touring and taught music in Hollywood while trying to find out what had gone wrong with his health. Doctors diagnosed him with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, leading him to receive electric shock therapy before he was treated for an arteriovenous malformation in his brain.

His recovery was slow, and it was soundtracked by his old records, which his father played for him while Martino recuperated in the family home. “I would lie in my bed upstairs and hear them seep through the walls and the floor, a reminder of something that I had no idea that I was supposed to be anymore, or that I ever was,” he recalled in an autobiography, Here and Now! (2011), co-written with Bill Milkowski.

Martino said his muscle memory returned in snatches as he recovered many of his old techniques. He started performing again after two years, and released a comeback record, The Return (1987), only to go on a hiatus when his parents became ill and died within a year of each other. He fell into depression and faced additional health problems, including emphysema, before returning to the studio to record two albums in six months – Interchange (1994) and The Maker (1995).

His other records included All Sides Now (1997), in which he teamed up with revered guitarists such as Les Paul and Joe Satriani; Undeniable (2011), recorded live at Blues Alley in Washington; and Formidable (2017), his last record leading a band, which included two members of his long-time trio, organist Pat Bianchi and drummer Carmen Intorre Jr.

Survivors include his wife of 26 years, previously Ayako Asahi.

Martino was the subject of a 2008 documentary, Martino Unstrung, which examined his recovery from brain surgery. One scene showed him looking at images of his brain, where a black spot marked the missing 70 per cent of his left temporal lobe, according to an account in Nautilus magazine. He had lost almost all of his memories, he noted, as well as a critical outlook on life.

“I would say that what is missing is disappointment, criticism, judgment of others – what is missing are all of the dilemmas that made life so difficult,” he said in the film. “That’s what’s missing. And to be honest with you, it’s beneficial.”

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments