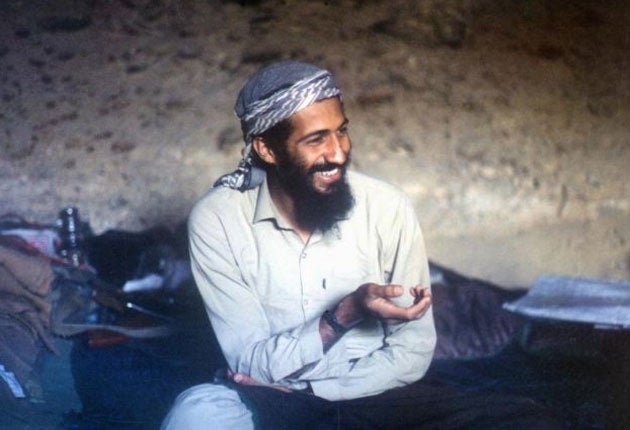

Osama bin Laden: Terrorist leader who waged jihad against 'Jews and Crusaders' and ordered the attacks of 11 September 2001

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Osama bin Laden was the last of a trio of charismatic Arab leaders who emerged in the second half of the 20th century to challenge the dominion of Western values and influence in the Arab world. If Gamal Abdul Nasser in Egypt, Saddam Hussein in Iraq and Osama bin Laden in Saudi Arabia and Afghanistan all enjoyed a measure of success, they ultimately brought catastrophe on their supporters.

All three sought, with varying degrees of sincerity, to assuage the sense of injury that can be traced back, in the first instance, to the Allies' betrayal of Arab hopes at the collapse of the Ottoman Empire at the end of the First World War. Bin Laden sought to extend his constituency to the entire Muslim world and found adherents as far east as the Philippines and as far west as the continental United States.

All three overestimated their own strength and underestimated that of their foes. All ended up at odds with the greatest power on earth, the United States, and, through their recklessness, brought Western armies back into the Middle East. The popular uprisings this year in Tunisia, Egypt and Syria suggest that younger Arabs may have turned their backs on all three men and concluded that the path to Arab independence and dignity runs not through the suicide belt but the ballot box.

Six feet three inches in height, Osama bin Laden was a handsome man. Visitors remarked on his beautiful manners and quiet speech, his accurate Arabic free of seminary affectation, his Hatim-like generosity with his inherited fortune, his hypochondria and good humour. Kalashnikov semi-automatic weapon at the ready, a master of international commerce and satellite communication, Bin Laden seemed to embody a new and romantic model of Arab masculinity. Unlike many Muslim revolutionaries, he did not waste his breath on Western social customs or in hectoring respectable women.

While Bin Laden sought to imitate the Prophet of Islam in his personal conduct, his unconscious models were the anti-colonial revolutionaries of the 1960s. His love of mountains, "clean air you can breathe without humiliation", was European, even touristic. In retrospect, he was a synthetic creation of two cultures at the point of collision, a sort of Arabian Crazy Horse.

Bin Laden's message combined the pious xenophobia of Saudi Arabia with the brutality of the Islamic movements of Egypt and Algeria. Though his purpose was to seize power in the Arab capitals, such as Cairo and Riyadh, his principal target was not the Arab kings or dynastic presidents but their ally, the United States. The US was for him an idol to be smashed, like the colossal Buddhas in the Bamiyan Valley destroyed by his Afghan allies, the Pashtun movement known as the Taliban, or the twin towers of the World Trade Centre in New York.

Muslim rulers, including those of his native Saudi Arabia, were to him merely apostates deserving of death. The Islamic government he financed for the Taliban, which reduced 1,400 years of Islamic civilisation to a gruesome moral police known as amr bil-maaroof wa hayy an al-munkar [Encouraging the Proper and Discouraging the Improper] was never likely to appeal to the Arabic- or Persian-speaking mainstreams. The brutality of his self-styled successors, such as Abu Musab al-Zarqawi in Iraq and Jordan, threatened a sectarian bloodbath that revolted Arab opinion. In reality, Bin Laden's world was a Manichean waste in which a self-professed vanguard of Muslims battled "Jews and Crusaders" to annihilation.

Bin Laden's preferred weapon, which he did not originate but deployed to catastrophic effect, was the suicide attack. In the course of the 1990s, Bin Laden and his Egyptian allies built up a network of cells in the Middle East and Africa of men willing to give their lives to kill those whom they perceived to be enemies of Islam. The older of these were so-called Arab Afghans: foreign veterans of the war in Afghanistan who had been stranded at the Soviet withdrawal in 1989 with a taste for soldiering but no cause.

The suicide bomber had both tactical and propaganda merits. A cause for which a young man will murder women and children and also die must, self-evidently, be a very important one. Meanwhile, at each action the perpetrating cell destroyed itself, leaving investigators baffled at the chain of responsibility. The devastating potential of the suicide attack was revealed on 11 September 2001.

Tactical patience was not matched by strategic caution. Bin Laden, his Egyptian allies and the Taliban were unprepared for US retaliation. While many Arabs drew a sort of bleak satisfaction at the carnage on 11 September, they saw what its outcome would be and, once the war turned against Bin Laden, occupied themselves with other matters.

Once the American assault on Afghanistan began on 7 October 2001, both the Taliban and their Arab allies melted away, though Bin Laden managed to make his escape from the Tora Bora mountains of south-eastern Afghanistan some time in December. The US invasion of Iraq in 2003 offered al-Qa'ida an opportunity to regroup in a new territory, but the opportunity was squandered in an orgy of sectarian murder.

Osama bin Mohammed bin Awad bin Laden was born in Riyadh, the desert capital of Saudi Arabia, in 1957. His family, which hailed from the village of Rubat in Wadi Hadhramawt in Yemen, had come to the newly created Kingdom in 1930. His father, Mohammed bin Laden, founded a contracting company which prospered under the patronage of the Saudi royal family, building palaces, highways and works to accommodate the pilgrims at the two holy cities of Mecca and Medina. Osama, who was no doubt named after the Prophet's general Osama bin Zeid, was brought up first in Medina and then in Jeddah.

His father was the very model of a pious Arabian businessman. A pioneer of aviation in the country, he once claimed that his aircraft permitted him to pray in all three of Islam's holiest mosques in a single day. He died in an air accident in 1967. According to a historian of the Arabian merchants Michael Field, King Faisal banned the young Bin Ladens from flying their own aircraft: something of an omen, in retrospect. Osama's elder brother Salem, who built up the multi-billion-dollar business now known as the Saudi Binladin Group, himself died at the controls of a small aircraft in Texas in 1988.

Unlike Salem, who was educated in England, married an Englishwoman and charmed the expatriate society of Jeddah, Osama once said he gravitated towards Islamic opposition from as early as 1973. Ever since the 1960s, the Saudi universities had given refuge to Muslim Brothers fleeing persecution in the secular Arab republics, notably Egypt. At King Abdul Aziz University in Jeddah, where he studied for a degree in economics and public administration, Osama may have come into contact with Abdullah Azzam, the Palestinian Islamist, and Mohammed Qutb, brother of the radical philosopher Sayyid Qutb and a leading influence on the Egyptian Islamic underground that was about to break into the open with the assassination of President Anwar Sadat in 1981. Osama was to join forces with Azzam in Peshawar in recruiting Arab Afghans and later amalgamate with the Egyptian group responsible for Sadat's murder, Islamic Jihad.

At the close of 1979 (or rather the opening of the Muslim year 1400), Saudi Arabia was convulsed first by the capture of the Grand Mosque in Mecca by millenarian insurgents and, in the next month, by the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. By his own account, Bin Laden was in Afghanistan within a few weeks of the invasion, and the next decade was to see him shuttling back and forth, marshalling his family's international contacts, its expertise in explosives and military construction, and its money in the support of the Afghan resistance. In 1984, he set up with Abdullah Azzam in Peshawar the so-called Services Office, or Maktab al-Khidamat, to recruit and ship Arab volunteers into Afghanistan. He struck people at that time as sincere and vigorous, but no leader of fighting men.

In 1986, he founded a camp in Paktia province in Afghanistan, al-Ansar (the name for the Prophet's companions in Medina) which was attacked by the Soviets the following spring. Bin Laden's conduct at that battle, and again in fighting for Jalalabad in 1989, gave him a reputation as something more than a builder and financier.

Despite ill-health, which caused him to walk with the help of a stick, Bin Laden at that period gave an air of omnipotence. He later told Peter Arnett of CNN: "The glory and myth of the superpower was destroyed not only in my mind, but also in the minds of all Muslims." In Peshawar, he came into contact with the Egyptian revolutionaries of Islamic Jihad, including Ayman al-Zawahiri, who had come to Peshawar to work as a physician among the Afghan refugees. In 1988 or 1989, as the Soviets prepared to withdraw from Afghanistan and Azzam was assassinated, Bin Laden and al-Zawahiri founded al-Qa'ida (The Base). While its original purpose is not clear, al-Qa'ida developed into an organisation to deploy the Arab Afghans – those latter-day Wild Geese – on his enemies outside Afghanistan.

Back in Saudi Arabia, at the age of 32, Bin Laden came into conflict with the House of Saud. With Saddam's invasion of Kuwait in the summer of 1990, Bin Laden volunteered the services of the Afghan veterans to expel the Iraqis, as they had the Russians from Afghanistan. The Saudi royal family instead invoked the help of the US, which began despatching troops to the kingdom on 7 August 1990. For Prince Turki al-Faisal, the son of the old King who was director of Saudi general intelligence and had co-ordinated Saudi support for the Afghan resistance, this was the turning point: "I saw radical changes in his personality," he told the Arab News of Jeddah in November 2001, "as he changed from a calm, peaceful and gentle man interested in helping Muslims into a person who believed that he would be able to amass and command an army to liberate Kuwait. It revealed his arrogance and his haughtiness."

Osama bitterly opposed the presence of Christian forces in Arabia, and his opposition was echoed by several popular preachers. Frustrated, in 1991, he moved to Sudan, where he found a welcome from Hassan al-Turabi, the founder and leader of the National Islamic Front.

While in Sudan, Bin Laden set up commercial enterprises, none of which appears to have prospered, while preparing his first action against American interests, with the bombing of two hotels housing US servicemen in Aden in December 1992. He was also to claim credit for training the Somali insurgents that brought down two US Sikorsky Black Hawk helicopters in Mogadishu the following October, killing 18 Americans. The sudden US withdrawal from Somalia caused him to jeer at the "weakness, frailty and cowardice of US troops". The first bombing of the World Trade Centre by the Baluchi explosives expert Ramzi Yousef in 1993, and the attacks on US servicemen in Riyadh in 1995 and Dhahran in 1996, may or may not have had his direct involvement.

In 1994, Osama was stripped of his Saudi citizenship and disowned by his family. Two years later, the Sudanese were seeking to be rid of him, and in May 1996 he returned with his three wives and some of his children to Jalalabad, which fell to the Taliban that August. In November, Abdul Bari Atwan, editor of the London newspaper Al-Quds Al-Arabi, visited Bin Laden in his cave hide-out, surrounded by grenades and books of devotion and theology. Early the next year, Bin Laden moved to Kandahar, where he became friendly with Mullah Omar, the leader of the Taliban, and gained a mysterious command over the newly acclaimed Prince of the Faithful.

On 23 February 1998, he announced the creation of a World Islamic Front for Jihad against Jews and Crusaders. In rhyming Arabic prose which has been admired by some connoisseurs, Bin Laden, Ayman al-Zawahiri and other radicals accused the US of occupying and despoiling the "sacred lands of Islam" and issued this fatwa, or legal ruling: "It is an individual obligation for every Muslim who is able to do so in any country to kill and fight Americans and their allies, whether civilians or military..." On 7 August, at 10.30am, a lorry containing hundreds of pounds of TNT and aluminium nitrate blew up in the car park of the US embassy in central Nairobi, killing 201 Kenyans and 12 Americans. Nine minutes later, a second suicide bomb exploded at the embassy in Dar es Salaam in Tanzania, killing 11 Tanzanians, almost all of them Muslim.

Five years of planning went into the suicide attacks, code-named Holy Kaaba (Kenya) and al-Aqsa (Tanzania). Their complexity, scope, precision and indiscriminate savagery set an ominous precedent that the Clinton administration did not take to heart. Instead, the US fired dozens of cruise missiles at al-Qa'ida camps in the Khost district of eastern Afghanistan, and a Khartoum factory. The Afghan missiles had no effect except to infuriate Mullah Omar and embarrass Prince Turki's negotiations in Kandahar to have Bin Laden extradited to Saudi Arabia. By the middle of 1999, Bin Laden was exulting in the Nairobi bombing: "God's grace to Muslims that the blow was successful and great."

An attack on the American mainland to coincide with the new Christian millennium was frustrated. But on 12 October of the next year, two suicide bombers brought a dinghy alongside the destroyer USS Cole in Aden harbour, and detonated it, killing 17 sailors.

By the beginning of 2001, reports began to surface in London and elsewhere that al-Qa'ida would soon launch another long-prepared attack. But nothing had prepared the world for the airliners that drove into the towers of the World Trade Centre, killing almost 3,000 people. It is possible that Bin Laden expected, even invited, a US assault on Afghanistan. On 9 September, two days before the suicide attacks on the World Trade Centre and Pentagon, two Moroccan Arabs posing as journalists blew up Ahmad Shah Massoud, the United Front commander most feared by the Taliban.

Of his escape from Afghanistan and life in hiding, we know little. His communications with the outside world by means of audio- and video-tape slowed to a trickle, and by 2007, dried up. Even before then, he seemed to be commenting on events rather than initiating them. In any case, the cause of violent jihad had long passed to new recruits, many of them European Muslims of the second generation, to whom Osama was an inspiration rather than a guide.

In his violent career, his fatwas and his interviews, Osama bin Laden attempted to portray Islam as a civilisation that had no choice but to murder, or kill itself. Whether his death has broken the spell of this nihilism, or inaugurates a new cycle of violence, is a question that may be asked but not yet answered. While the West seems determined, through its military actions in Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya, to give the Arabs and Muslims new cause for grievance, the "Arab Spring" may tell us that history has moved on.

Osama bin Mohammed bin Awad bin Laden, terrorist leader: born Riyadh, Saudi Arabia 10 March 1957; married approximately five times (12-24 children); died Abbotabad, Pakistan 2 May 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments