Ollie Johnston: Last of Disney's 'Nine Old Men'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

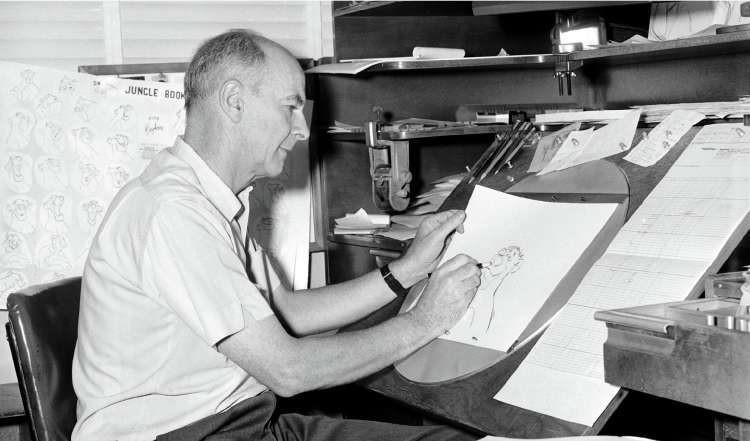

Your support makes all the difference.Ollie Johnston was the last surviving member of the legendary group of animators dubbed "the Nine Old Men" who worked at the pioneering Walt Disney studios from the mid-Thirties. He graduated from animating Mickey Mouse shorts to work on such classics as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Pinocchio, Bambi, Cinderella and The Jungle Book.

Sequences he had a hand in creating included Pinocchio's nose growing as he lied to the Blue Fairy, Thumper's account of eating greens under his mother's watchful eye in Bambi, and the penguin waiters who served Julie Andrews and Dick Van Dyke in Mary Poppins. Roy Disney, Walt's nephew and a director of the Disney Corporation, said, "One of Ollie's strongest beliefs was that his character should think first, then act, and they all did."

Johnston, who described his talent as "intuitive", said that his aim was to make the films "believable rather than realistic. I made Bambi's snout smaller than a real deer's, for example, the better to animate his expressions." The animator Andreas Deja described how impressed he was when he first saw the moment in Bambi when the fawn sees his father, the Great Prince, for the first time:

The Great Prince passes by, very serious and stern, and very slowly Bambi's expression changes: he drops his ears slightly and looks a little scared. It's a scene that's so subtle, you think it couldn't be done in animation. When you want to show a change, you have to make it graphically clear and Bambi is undergoing such a subtle mood shift. But Ollie handled it with such tact and sensitivity.

Johnston was particularly proud of the memorably moving sequence that conveys the death of Bambi's mother. "It showed how convincing we could be at presenting really strong emotion." The animator John Canemaker described Johnston's death as "truly the end of the 'golden age' of hand-drawn Disney character animation that blossomed in the 1930s".

The son of a professor who headed the Romance languages department of Stanford University, Johnston was born in Palo Alto, California in 1912, and studied art at Stanford, where he met Frank Thomas, who was to become another member of the "Nine Old Men" and a lifelong friend – the pair were to become neighbours in Los Angeles and their wives were to become best friends. Johnston and Thomas later wrote four highly regarded books together.

Johnston's initial ambition was to be a magazine illustrator: "I wanted to paint pictures full of emotion that would make people want to read the stories, but I found that here in animation was something that was full of life and movement and action, and it showed all those feelings." He and Thomas continued their studies at the Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles, where they were spotted by Walt Disney, who hired Thomas, then a few months later Johnston, to work at his studio.

As an assistant to the established animator Fred Moore, who had made such shorts as The Three Little Pigs and several Silly Symphony cartoons, Johnston's first film was the Mickey Mouse short Mickey's Garden (1935), and his skills were further displayed in his work with Moore on the shorts Pluto's Judgment Day (1935) and Mickey's Rival (1936). After assisting Moore animating the dwarfs in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), he graduated to full animator with one of the finest of Mickey Mouse subjects, The Brave Little Tailor (1938), the success of which prompted Disney to ask Moore and Johnston to become principal animators on Pinocchio (1940).

Johnston always credited the enormous influence that Disney himself had on the work of his team. He and Thomas wrote,

Walt was so immersed in his characters that, at times, as he talked and acted out the roles as he saw them, he forgot that we were there. We loved to watch him; his feelings about the characters were contagious. The most stimulating part of all this to the animators was that everything Walt was suggesting could be animated. It was not awkward continuity or realistic illustrations but actions that were familiar to everyone.

Pinocchio was to become one of Disney's most celebrated classics, a timeless joy, technically brilliant, with some of the genre's most endearing characters, as well as some of the most sinister. Johnston worked on many Disney classics that followed, including Fantasia (1940, the "Pastoral Symphony" section), Dumbo (1941), and Bambi (1942). For the wartime short Der Fuehrer's Face (1942), he drew on some of the surrealistic expression first seen in Dumbo, and he contributed to the propaganda piece Victory Through Air Power (1943).

The beguiling mixture of animation and live action Song of the South (1946) featured Johnston's animation of the storybook characters Brer Rabbit, Brer Fox and Brer Bear, and for a witty adaptation of Kenneth Grahame's The Wind in the Willows, which formed part of The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr Toad (1949), Johnston produced one of his most memorable villains, the unpleasant prosecuting barrister who tries to confuse Toad on the stand. Johnston said, "He was based on bullies that I had known at school."

Other villains he created included the stepsisters in Cinderella (1950), Mr Smee in Peter Pan (1953) and Sir Hiss in Robin Hood (1973). In the same film he animated Prince John, voiced by Phil Harris who, as the kindly bear Baloo in a sequence animated by Johnston for The Jungle Book (1967), had introduced the song "The Bare Necessities".

He supervised the depiction of all the leading characters in The Sword and the Stone (1963) and for one of his last films prior to his retirement, The Rescuers (1977), he conceived the warm-hearted old cat Rufus as a partial self-caricature – Johnston wore a similar moustache and glasses.

In retirement, Johnston lectured, pursued his passion for model steam locomotives and wrote four books with Thomas, including Disney Animation: the illusion of life (1981), considered "the bible of animation". In 1995 Thomas's son and daughter-in-law produced a film documentary, Frank and Ollie: drawn together, which celebrated the lives and friendships of Thomas and Johnston.

Tom Vallance

Oliver Martin Johnston, animator: born Palo Alto, California 31 October 1912; married 1943 Marie Worthey (died 2005; two sons); died Sequim, Washington 14 April 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments