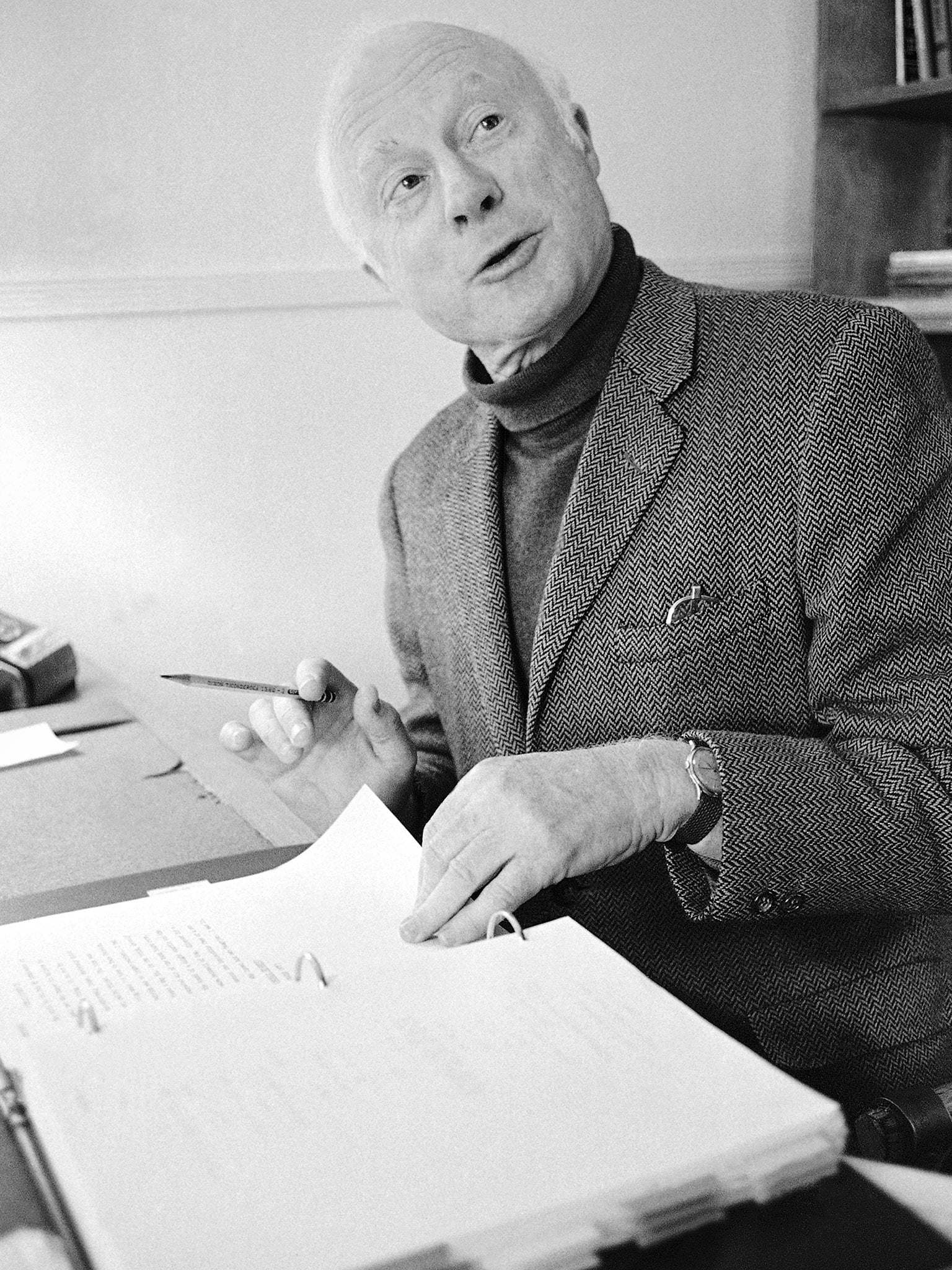

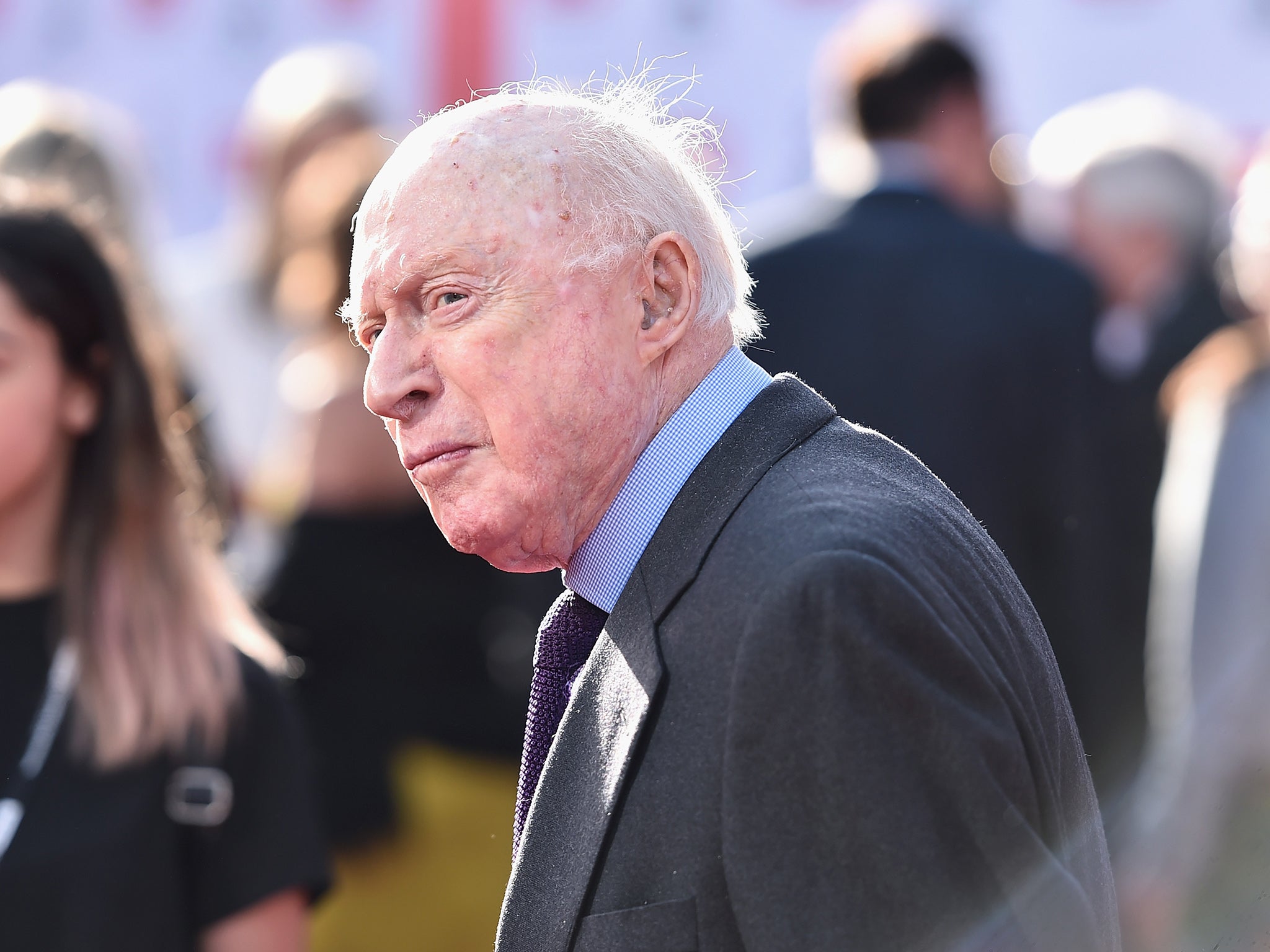

Norman Lloyd: Legendary actor who starred in Saboteur and St Elsewhere

The New Jersey native made a speciality of playing unsavoury roles during his glittering nine-decade career

Norman Lloyd, a venerable character actor for nine decades who may be best remembered for playing the villain who dangles from the Statue of Liberty at the climax of Alfred Hitchcock’s Second World War thriller Saboteur, has died aged 106.

In a prolific and varied career, Lloyd worked under director Orson Welles in his celebrated Mercury Theatre shows of the late 1930s. He also befriended Charlie Chaplin on a Hollywood tennis court and was rewarded with a supporting role in the director’s last American-made film, Limelight (1952). He became one of Hollywood’s oldest active performers, appearing as a lecherous senior citizen in Judd Apatow’s romantic comedy Trainwreck (2015).

On-screen, Lloyd made a speciality of playing unsavoury roles. After his feature-film debut with Saboteur in 1942, he played a psychologically disturbed patient in Hitchcock’s Spellbound, a vindictive farmhand in Jean Renoir’s The Southerner and a cynical soldier in Lewis Milestone’s antiwar film A Walk in the Sun (all 1945).

As the decades passed, Lloyd’s Old Broadway theatrical mannerisms, professorial speaking style (he called movies “the pictures”) and prematurely balding pate led to officious parts in film and on TV.

He was the haughty headmaster who antagonises an idealistic English teacher (Robin Williams) in the movie drama Dead Poets Society (1989) and the aged lawyer Mr Letterblair in The Age of Innocence (1993), director Martin Scorsese’s film version of the Edith Wharton novel.

Lloyd developed a strong following as a crusty but likeable hospital administrator Dr Daniel Auschlander on the NBC medical drama St Elsewhere, which aired from 1982 to 1988.

“The original character of Dr Auschlander was only supposed to go for four episodes because he had cancer of the liver,” Lloyd told a Los Angeles theatre publication. But the audience response proved so enthusiastic, he added, that “the character went for six years with the longest remission on record”.

In more recent years, Lloyd was an in-demand public speaker who reminisced about his links to creative giants of the early and mid-20th century.

Welles, he said, liked to sate his ample appetite in front of starving actors during the Depression. “One day a woman in the cast crept forward and begged for one strawberry from his tart,” he told the Los Angeles Times. “He sent her away with a bellow that shook the theatre.”

Hitchcock liked to make macabre jokes about his great-granddaughter being eaten by a hungry dog. “That’s the way Hitch saw things,” he said. “Humour mixed with suspense.”

More than a living museum, Lloyd remained a committed working actor. He displayed a beginner’s enthusiasm upon learning he was being considered for a role as a Marxism-spouting intellectual in the Coen brothers’ 2016 film Hail, Caesar! Because one of the scenes was to be filmed at sea aboard a submarine, the producers raised concerns about Lloyd’s age.

“They’ve since cast the part with a much younger man,” he later mock-griped to Variety. “In his eighties.”

Norman Perlmutter was born in New Jersey on 8 November 1914. He grew up in Brooklyn, where his father worked in the furniture business. His theatre-loving mother insisted on elocution lessons to rid him of his Brooklyn accent. That instead led to singing and dancing classes.

He made his debut, he recalled, in a neighbourhood ladies’ club show of dubious taste. “‘Father, Get the Hammer, There’s a Fly on Baby’s Head’ – that was my big number,” he told the Newark Star-Ledger. “So you can imagine what that act was like.”

In the early 1930s, he apprenticed with Eva Le Gallienne’s Civic Repertory Theatre in New York. He then acted with the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Theatre Project and participated in its “living newspaper” unit that put on plays and sketches to dramatise social conditions in America, including the plight of the Dust Bowl farmer during the Depression.

Welles and producer John Houseman, who had worked with the Federal Theatre Project, invited Lloyd to join their new company of actors called the Mercury Theatre. In one of their most renowned productions, Lloyd played the poet Cinna in Julius Caesar (1937), a modern-dress version of Shakespeare’s play that Welles envisioned as a parable of the Italian fascist leader Benito Mussolini.

A few years later, when Welles was put under contract at RKO studios to film Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, Lloyd was among the crew to tag along. The project fell through, and Lloyd, an expectant father with a family to feed, said he couldn’t afford to hang around while Welles completed another film he was working on, Citizen Kane.

Lloyd went back to the New York stage until Houseman brought him to the attention of Hitchcock, who was seeking an unknown to play the heavy in Saboteur. The film was not well received – many critics found it to be a warmed-over version of Hitchcock’s innocent-man-on-the-run masterpiece The 39 Steps (1935), only steeped in wartime propaganda.

The star was Robert Cummings as the man who must clear his name from a sabotage charge. But it was Lloyd who was singled out by critics for his thoroughly ratlike performance as Frank Fry.

The French passenger ship Normandie burned at her Manhattan pier during filming, and Hitchcock quickly inserted a scene with Lloyd passing by the wreckage in a cab, taking smug satisfaction in what viewers are to assume is his handiwork.

Saboteur is also widely recalled for its smashing, near-silent finale atop the Statue of Liberty. In the sequence, Lloyd does a backflip over the railing, which leads to him clinging desperately to an edge of the monument. Cummings tries to rescue him, grabbing his sport coat, but the seams tear one by one, and he plunges to his death.

The role brought Lloyd steady work over the next decade, mostly in sneering roles but also as a minstrel in The Flame and the Arrow (1950), a costume action drama with Burt Lancaster, and as a stage manager in Limelight, in which Chaplin played an ageing vaudeville comic. It was the last film Chaplin made before his 20-year self-imposed exile in Switzerland, fleeing from US government officials who condemned his left-leaning political views.

Lloyd also was an ardent political liberal who had many friends on the far left, dating to the 1930s theatre scene in New York. He was appalled by old acquaintances such as director Elia Kazan cooperating with the anti-communist witch hunt at the time.

Lloyd said that he was never called to testify at any hearings, but that he was the subject of whisper campaigns that dried up his acting prospects.

During those lean years, he said, he relied on old friends for support. “We went back to New York,” he told the Star-Ledger. “Jack Houseman had a vacant house there, and he insisted – and this is the kind of man he was – that we’d be doing him a favour by moving into it … Eventually I got a job directing industrial films for $150 a week.”

Hitchcock came to his rescue, hiring him in 1957 as a director and producer of the CBS TV series Alfred Hitchcock Presents. Over the next several decades, Lloyd worked intermittently as a director and producer of TV movies such as The Carpenters (1974), based on a comic play by Steve Tesich, and TV series including Tales of the Unexpected.

His wife of 75 years, actress Peggy Craven Lloyd, died in 2011. His daughter, Susanna Baird, who had acted under the name Josie Lloyd, died in 2020. In addition to his son, survivors include a sister, a grandson and three great-grandchildren.

Norman Lloyd, actor, born 8 November 1914, died 11 May 2021

© The Washington Post

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks