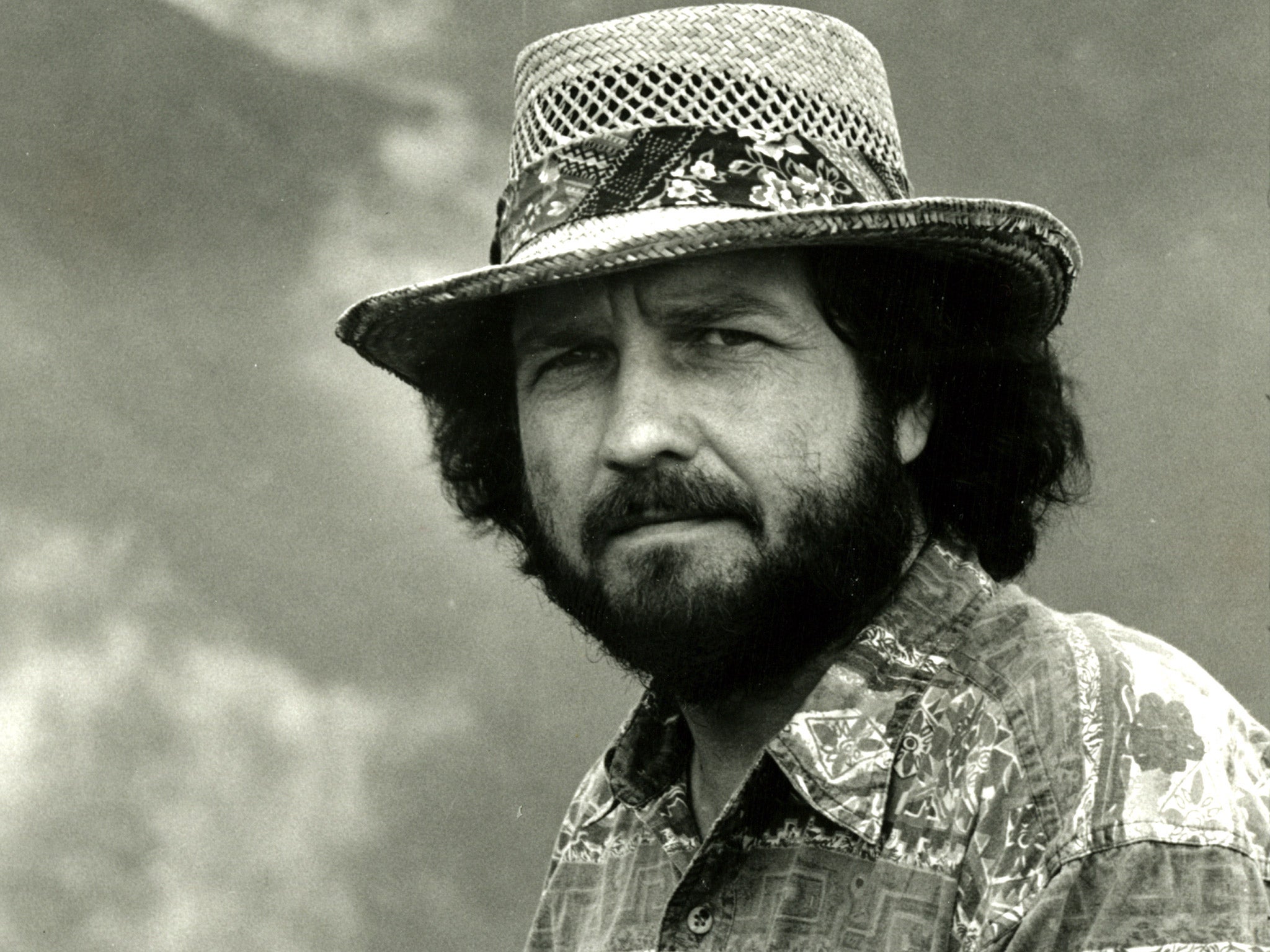

Nigel Jenkins: Politically engaged and outspoken poet whose work often landed him in trouble with the officials he meant to offend

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Of all Welsh poets writing in English, Nigel Jenkins was one of the most politically engaged and outspoken. His views and actions often got him into hot water.

In 1988 he was jailed for seven days for refusing to pay a £40 fine imposed after a protest outside the American airbase in Brawdy, in Pembrokeshire. He had cut the perimeter fence as part of CND's Operation Snowball, a campaign aimed at persuading the government to vote in favour of multilateral disarmament. "I consider it my duty as a Welshman and an internationalist," he told reporters, "to do all in my power to end the continuing presence on Welsh soil of American and British nuclear bases." In 1987 he co-edited the anthology Glas-Nos for CND Cymru.

Jenkins believed, unlike Auden, that poetry could make things happen, especially in Wales, where poets are often called upon to write verse that inspires the community to take action against overweening officialdom. His poems were meant to offend, and offend they often did. When his "Execrably Tasteless Farewell to Viscount No" appeared in The Guardian in 1997, he was pilloried for satirising George Thomas, the recently deceased Commons Speaker who had been prominent in the No camp during the Devolution campaign. It was the vitriolic language that raised most hackles: "white man's Taff ... may his garters garrotte him ... the Lord of Lickspit, the grovelsome brown-snout and smiley shyster whose quisling wiles were the shame of Wales..."

Jenkins courted controversy whenever possible. Commissioned (with Menna Elfyn and David Hughes) in 1993 to write site-specific poems for the refurbished city centre in Swansea, his native place, he jumped at the opportunity to give poetry the public profile he believed it should have in the lives of the people: "It is my fortune to work in a country which, unlike its neighbour to the east, has an unbroken tradition of poetry as a social art."

But most of the one-liners such as "Remember tomorrow" inscribed on benches, flagstones, walls, bollards and signposts, were obliterated or removed – not by vandals or hostile citizens but by council employees. When confronted by the irate poet, an official was quoted in The Independent as saying, "People find poetry irrational and strange. They don't understand it. They're frightened by it."

The irony was that Swansea was to be a City of Literature in 1995. Jenkins had expressed disquiet about the concept long before the spat over the lapidary inscriptions. Unhappy at the exclusion of local writers, he had set up the Swansea Writers and Artists Group (SWAG) to remind the organisers of their existence. In the event, the year of literature proved little more than an exercise in civic philistinism and internecine strife among the literati. Jenkins also served as the first secretary of the Welsh Union of Writers, another campaigning group, but it had little clout with funding bodies.

He was a man of the Left, his political views finding expression in the ranks of Plaid Cymru, and he served on the editorial board of Radical Wales, though as a Welsh republican he sometimes groaned at the party's shortcomings. "It is difficult to write effective political poetry," he once told an interviewer, "in the same way that it must be difficult to write religious poetry, without banging the drum and thumping the tub. I have fallen into such error all too readily. On the other hand, there is scope for the political poem which may not have much of a shelf-life but which has a job to do, gets in there, blazes away and gets out again."

Nigel Jenkins was born in Gorseinon, Swansea, in 1949 and raised on his parents' farm in Gower. He worked for four years as a reporter in the English Midlands and then, after wandering in Europe and North Africa, and working as a circus-hand in America, studied comparative literature and film at Essex University. He returned to Wales in 1976, settling in Mumbles on Swansea Bay and earning a living as a freelance writer. With his rich voice, the blackest of beards and rugged good looks, he was a popular participant in readings and conferences. A kind, eirenic and selfless man, he was generous with others and especially so with younger writers, whom he encouraged and whose work he promoted.

He first came to prominence as one of three young poets named by the Welsh Arts Council in 1974. From the start his concern was with Wales and its place in the world. His poems are in turn local, cosmological, satirical, playful, bitter, comic, ribald, and dismissive. They are to be found for the most part in Song and Dance (1981), Practical Dreams (1983), Acts of Union (1990), Ambush (1998) and Hotel Gwales (2006). He also published two collections of haiku and senryu, namely Blue (2002) and O for a Gun (2007); the traditional Japanese forms lent themselves well to the concise wit and withering satire of which he was a master.

Two books of prose added to his reputation: Gwalia in Khasia (1995) is about Welsh missionaries in the Khasi hills of north-east India while Footsore on the Frontier (2001) brings together a selection of his miscellaneous essays. The first of these, selected as the Wales Book of the Year in 1996, was compared by competent critics to the work of such travel-writers as Jan Morris and Paul Theroux. He also wrote a warmly appreciative monograph on John Tripp, a fellow-poet whose search for any sign of benevolent grace struck a chord with him.

Jenkins' theatre work included Waldo's Witness (Coracle, 1986), about the great pacifist poet Waldo Williams, and Strike a Light! (Made in Wales, 1989), about the Chartist and pioneer of cremation, Dr William Price. Two coffee-table books followed: The Lie of the Land (with photographer Jeremy Moore, 1996) and Gower (with David Pearl, 2009). He also edited the symposium Thirteen Ways of Looking at Tony Conran (1995), in homage to a poet he greatly admired, and served as one of the co-editors of The Encyclopaedia of Wales (2008). His two books on Real Swansea (2008, 2009) are a psychogeography of the "ugly, lovely" city which he knew in intimate detail.

MEIC STEPHENS

Nigel Leighton Rowland Jenkins, poet and political activist: born Gorseinon, Swansea 20 July 1949; married Delyth Evans (marriage dissolved; two daughters); died Swansea 28 January 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments