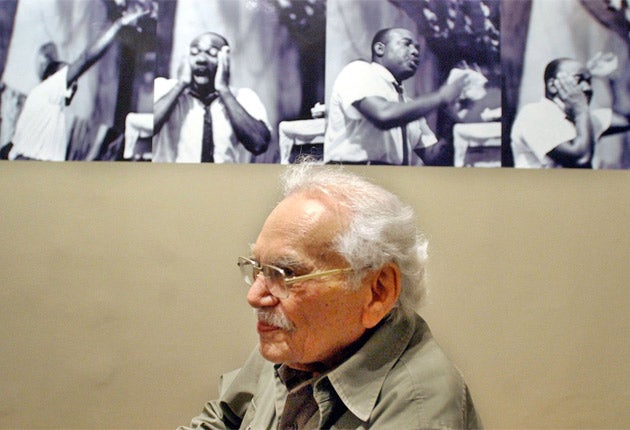

Milton Rogovin: Photographer who chronicled the lives of working people and impoverished Americans

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Milton Rogovin, blacklisted during the McCarthy era, was an optometrist who went on to become one of America's best-known social documentary photographers. For more than 50 years, his award-winning photographs chronicled and championed the rights of the disenfranchised, the working class and the underprivileged. He called these people "the forgotten ones".

Rogovin published several books, and his work was exhibited internationally; his images are held in major collections including those at the J Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, The Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, MoMA in New York, the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, and The Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Today, his entire archive resides in the Library of Congress in Washington DC.

Born in Brooklyn in 1909 to Jewish Lithuanian immigrants, Rogovin was the third of three sons to Jacob and Dora, who ran a dry-goods business. He studied optometry at Columbia University, graduating in 1931, before moving to Buffalo in 1938 to open his own practice. In the interim, his parents lost their home and business to bankruptcy during the Great Depression.

Before his move Rogovin had worked as an optometrist in Manhattan and became increasingly distressed at the plight of the poor and unemployed; he began to get involved in leftist causes. He attended classes sponsored by the Communist Party-run New York Workers School and was introduced to the social-documentary photographs of Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine.

In 1942, Rogovin married Anne Snetsky, a teacher, before volunteering for the army and serving for three years in England, working as an optometrist. After the war, he returned to his practice in Buffalo (run in his absence by his brother) and joined the local chapter of the Optical Workers Union; he also served as librarian for the Buffalo branch of the Communist Party.

In 1957, with Cold War anti-Communism rife in the US, Rogovin was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee, but refused to testify. Discredited – without having been convicted of any offence – and with his business all but ruined by the publicity, he began taking pictures, focusing on Buffalo's poor and dispossessed in the mainly black neighbourhood around his practice. He lived on his wife's teaching salary and was mentored by the photographer Minor White.

Initially, Rogovin's advances were met with suspicion by the black community, who suspected him of being from the police or FBI. He gradually built trust, giving away prints of portraits in exchange for sittings. He never told his subjects what to do, allowing them to pose in their own settings and clothes. His three-year documentation of Buffalo's black storefront churches and the communities surrounding them was his first major project. In October 1962, White published the series in Aperture magazine, with an introduction by the Civil Rights activist and journalist WEB Du Bois.

A 10-year project documenting the lives of Appalachian miners, and photographs of Native Americans on reservations near Buffalo followed, and Rogovin went on to photograph miners from around the world. He also created a series, Working People, photographs of steel and factory workers from New York. In 1967, he was invited to Chile by the left-wing poet Pablo Neruda; there he photographed Neruda's home and worked on the island of Chiloé. Neruda wrote an introduction to the series of Rogovin's Chiloé photographs.

In 1972, Rogovin embarked on perhaps his most notable work, a project on Buffalo's impoverished Lower West Side community, which saw him revisit and re-photograph over the next three decades. Also in 1972 he earned a Master of Arts in American studies from the University at Buffalo, where he taught documentary photography from 1972 to 1974. In 1983 he won the W Eugene Smith Memorial Fund Award for Documentary Photography, and in 2007 received the Cornell Capa Award from the International Centre of Photography in New York City. In 2003, he was the subject of an award-winning short documentary film by Harvey Wang, Milton Rogovin: The Forgotten Ones.

In 2003, Rogovin summed up his work: "All my life I've focused on the poor. The rich ones have their own photographers." As his health declined, Rogovin used a wheelchair and no longer took photographs. His activism, however, remained undimmed – he attended political rallies and anti-war protests into his final years – and his social conscience remained acute.

Martin Childs

Milton Rogovin, photographer: born Brooklyn, New York 30 December 1909; married 1942 Anne Snetsky (died 2003; one son, two daughters); died Buffalo, New York 18 January 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments