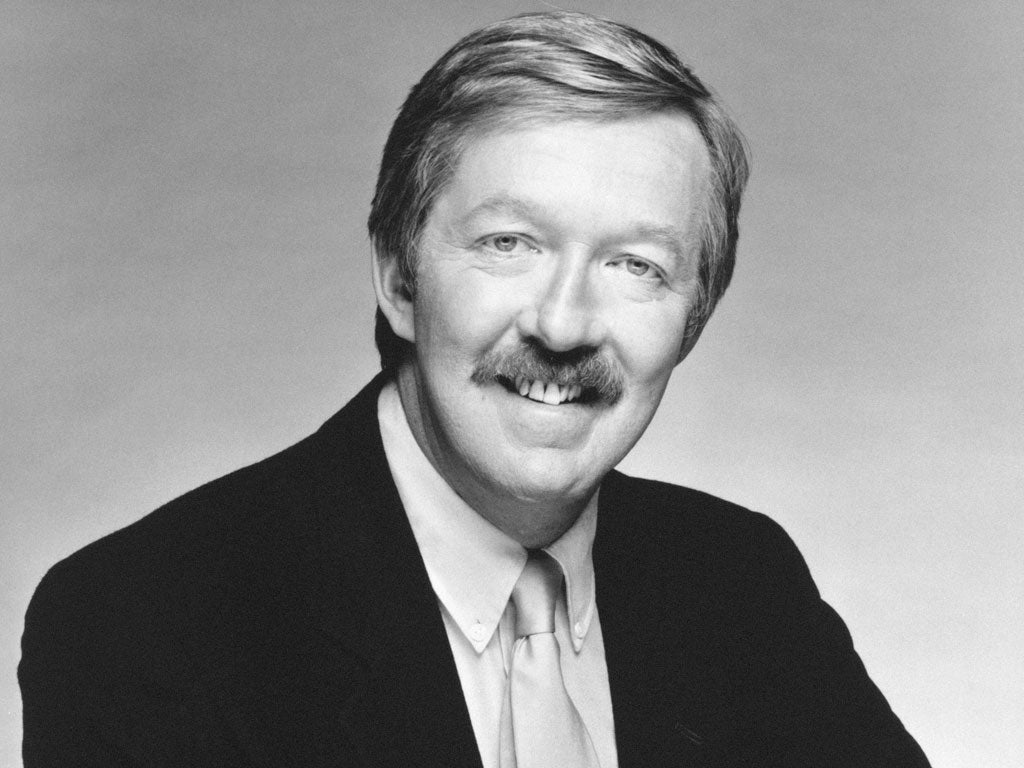

Mike Morris: Presenter who helped put TV-am on to an even keel

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The television critic Philip Purser commented on the arrival of breakfast television in Britain in 1983 that it was "rather like Milton Keynes. No one really wanted it but now it's there it's quite handy." Although the BBC's Breakfast Time programme was an instant success, and made a novelty into a habit within a few weeks, commercial television's first attempt, TV-am's Good Morning Britain, had a turbulent 10-year run of strikes, financial problems and oscillating ratings. But despite chaos behind the scenes, presenter Mike Morris remained genial, unflappable, and, that rare trait in presenters, sincere.

TV-am had got off on the wrong foot in February 1983, two weeks behind the BBC in its launch and assuming that the BBC's offering would be a news-based analytical show. They attempted to mimic this, with David Frost and Anna Ford, then found that the BBC had opted for a cosy, magazine-style programme which left theirs feeling starchy and dull. Viewers loved the cordial atmosphere on the BBC, conducted effortlessly by the epitome of middle-class respectability, Frank Bough, and within a few months it seemed that TV-am was finished.

Greg Dyke was brought in to "make it work", and the show was given a new look, Nick Owen, Anne Diamond and Roland Rat augmented by Morris, first as sports presenter and host of the Sunday edition, and then as one of the main weekday presenters from 1987. Ratings soon picked up, the show adopting much of the BBC's house style just as the Corporation, rather bafflingly, reinvented their programme as precisely the kind of news-based concept that had failed for TV-am. But things became even more unstable when new boss Bruce Gyngell responded to a technicians' strike by soldiering on using "cleaners as cameramen and secretaries as vision mixers." It made every morning's three-hour programme a chaotic affair, made worse when Gyngell sacked striking staff members.

None the less they had the audience by then, and managed to retain them. Morris was joined by Lorraine Kelly in 1990, and they made a good pairing. Under their reign TV-am was the most profitable station in Britain in terms of turnover and had a 75 per cent share of the breakfast audience. In his time on the show Morris interviewed everyone from Prince Edward to Joan Collins, even conducting Britain's first live television interview with Nelson Mandela, eight days after his release from prison. The show was easy, friendly, and finally a success.

Mike Morris was born in Middlesex and educated at St Paul's School in Barnes before reading English and American literature at Manchester University. His first job was on the weekly Surrey Comet in 1969, where he initially covered amateur theatre productions before becoming Entertainments Editor. He worked for AAP Reuters in Sydney in 1973, returning to England in 1974 to join United Newspapers as a sports reporter, within three years becoming Sports Editor. He entered television in 1979 to join the team of Thames Television's first wholly news-based daily programme, Thames at Six, a strong effort anchored by the no-nonsense Andrew Gardner, before his move to TV-am in 1983.

When TV-am lost its franchise in 1991, an incredulous Morris was "gutted", but as he left the building after the final programme some months later was typically good-humoured and said his situation was summed up by the fact that in the car was "a bottle of champagne and a P45."

Despite joking on air that he was going to become a passport-photographer, in 1994 he joined TV-am's replacement, GMTV, as host of Sunday Best, then went on the road for the relaunched Bristol-based WireTV with an outside broadcast unit that would spend each week in a different region. But despite being the first cable channel to secure the television rights to a major sporting event, the 1996 Cricket World Cup, the channel closed and Morris went to Yorkshire, where he had spent much of his childhood, to replace Richard Whiteley as host of the regional programme Calendar.

He stayed with the programme for six years before taking early retirement in 2002. His final television appearance was on a BBC documentary looking back at breakfast TV, in which Morris finally got the chance to display his cheekier side by describing Bruce Gyngell as "barking mad", and saying of former colleague Ulrika Jonsson's show Gladiators, "the last brain cell truly has left the country now."

He suffered from cancer in his final years and died of heart failure. Sadly he never fully realised his passion for sport on the screen, but deserves to be remembered for helping to make a programme with everything against it a major success.

Simon Farquhar

Michael Hugh Sanderson Morris, journalist and television presenter: born Harrow 26 June 1946; married 1975 Alison Jones (marriage dissolved; two daughters); died Surrey 22 October 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments