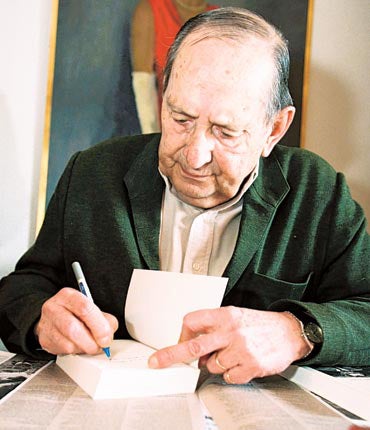

Miguel Delibes: Spanish writer who found a way past Franco's censors with his stark novels of rural and provincial life

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference."I write what I hear," Miguel Delibes, the Spanish novelist, once said. After winning the country's foremost literary prize when he was just 27, for more than half a century Delibes's hauntingly stark, gritty prose style captured the essence of Spain's rural and provincial life, and earned the writer massive popular and critical acclaim.

The author of 20 novels and over double that number of non-fiction works, Delibes's writing career effectively began with his wholly unexpected victory in the Nadal Prize in 1948 for his first novel, La sombra del ciprés es alargada. At the time a near-penniless journalist in his hometown of Valladolid, Delibes only discovered he had won as he was reading off the evening's dispatches on his newspaper's teleprinter.

"The prize was a unique opportunity; [normally] you couldn't publish anything," Delibes said later. "In the years after the Civil War, Spain had been struck dumb. All the writers had either been killed, exiled or had fallen silent. Literature was another victim of the war."

Slowly but surely, Delibes's unmistakeably concise, bleak writing helped rebuild Spain's literary legacy, both in the novels that appeared with unremitting regularity every two years, and in his five-year editorship of one of Spain's leading provincial newspapers El Norte de Castilla. "Journalism showed me how to put the maximum amount of information into the minimum number of words," Delibes said. As a liberal in Franco's dictatorship, journalism also showed him how to manipulate an apparently simple text so it would get past the censors with minimum interference.

Cinco horas con Mario ("Five hours with Mario") was just one of those subversive works that Delibes succeeded in publishing: in a lengthy monologue, the main character talks to her recently deceased husband – and unconsciously reveals some of the darkest and most miserable corners of everyday life under the ruling regime.

However, where Delibes was most at home as a writer was rural Castille. A keen hunter, fisherman and cyclist, he occasionally highlighted nature's idyllic side in works like El Camino ("The Road", 1950) – "That only got one page cut by the censors," he wryly observed later – but he also exposed its brutal, often cruel underbelly in Las Ratas ("The Rats", 1962). A violent and searingly accurate social allegory, Las Ratas flew in the face of the official version of rural Spain as the blissful, prosperous source of the country's essential moral values. It could hardly have gone unnoticed by the authorities – but somehow Las Ratas made it through.

Delibes's liberal-leaning editorship of El Norte de Castilla, as well as his undeclared leadership of a group of independent-minded intellectuals in Valladolid, brought him far bigger problems than his novels. In 1963, a series of run-ins with the Ministry of the Interior, most notably with Manuel Fraga – later a leading figure in Spain's post-Franco democracy – forced him to resign. By then, though, the increasing popularity of his novels and non-fiction (Delibes wrote widely on travel, fishing and hunting) earned him enough to support his large family. Not that this fame ever went to his head: sometimes his seven children would find their school lunch sandwiches had been wrapped up in the manuscripts of his earliest novels.

The early death of his wife, Angeles de Castro, in 1974, proved to be a far more devastating blow. Delibes always said that apart from being the love of his life, his wife had been the person who inspired him to read widely. She had also launched his career by encouraging him to send in his first novel for the Nadal Prize. Following his wife's death, Delibes continued both to write and rack up the literary awards – the National Literature Prize in 1955 and again in 1999, the Principe de Asturias in 1982, and the most important of all, the Cervantes Prize in 1993.

But without his wife, the mournful tone of his writing grew steadily more intense. On admission to the Royal Spanish Academy, one of the highest honours a writer can receive in Spain, Delibes's acceptance speech was entitled "A Dying World", studying the impact of human progress on nature. It later became one of the foundations for his work of the same name.

In 1993, Delibes announced – this time on accepting the Cervantes Prize – that he would be ceasing all activity as a writer; but he still had one card left up his sleeve. In 1998 he published El Hereje ("The Heretic"), a magnificent account of a Lutheran trapped by the Inquisition in Delibes's lifelong hometown of Valladolid. It was to be his last work and gained him a new wave of younger fans, although as Delibes once dryly observed, "the novel you have in your head is always better than the one you manage to write."

Alasdair Fotheringham

Miguel Delibes, novelist and journalist: born Valladolid, Spain 17 October 1920; married 1946 Angeles de Castro (died 1974; seven children); died Valladolid 12 March 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments