Micky Moore: Child star in the silents who became a director and worked with Spielberg

De Mille insisted on calling him 'Baby Moore' up until the 1950s: 'I think he knew it kind of upset me'

Micky Moore's career spanned 84 years of the picture business: from his start as a child actor in silent films, to second-unit director on Patton and Raiders of the Lost Ark. Before he was 15 he had worked on silent films with such directors as Tod Browning, Allan Dwan, and Cecil B DeMille, playing with stars including Mary Pickford, Tom Mix, and Gloria Swanson. He was Willie Lincoln in The Dramatic Life of Abraham Lincoln, released in 1924, almost 90 years before Steven Spielberg's version. Spielberg hired Micky as second-unit director on the Indiana Jones series and said, “Micky always gave me more than I ever hoped to achieve.”

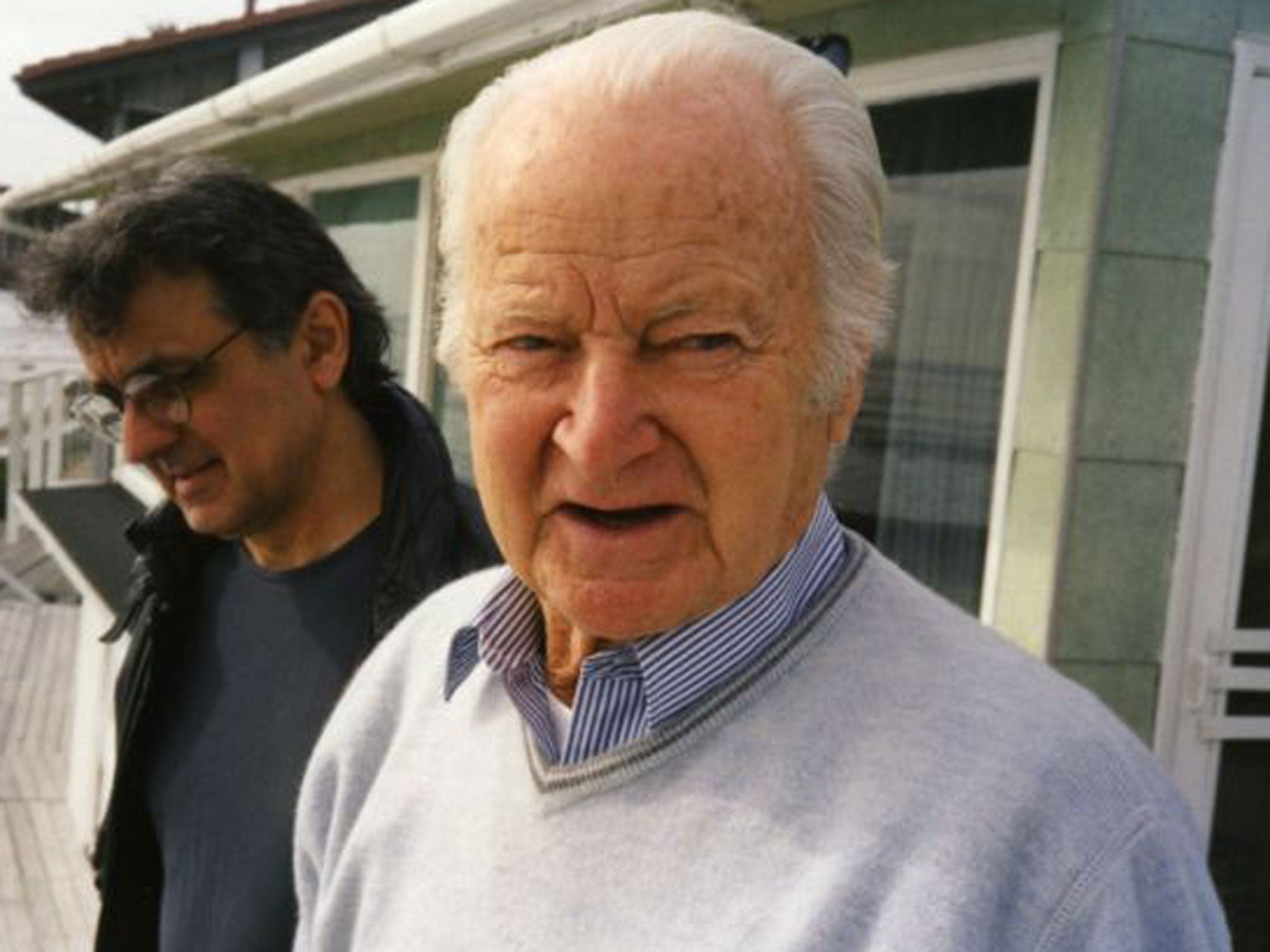

In 2001, I interviewed Micky for a documentary on DeMille, where he organised everything, including a lavish lunch. He was a powerful man, with the build of John Wayne, and a tough, punchy delivery, and an endearing habit of putting his arm on your shoulder to emphasise a point. His house sat right on Malibu beach; inside, a large ship's wheel dominated one wall, surrounded by production stills and posters, including a huge signed photograph of Elvis Presley, seven of whose pictures he worked on. A signed photograph from DeMille from 1951 read: “To Micky Moore – you gave a good performance for me 30 years ago – and you've been improving ever since,”

Dennis Michael Sheffield was born in Canada, one of three sons and one daughter of Norah Moore, an actress from Dublin, and Thomas Sheffield, an English marine engineer who founded the Santa Monica lifeguard service in 1916.

In 1915, the family moved from Canada to Santa Barbara, California. Sidney Algiers, business manager for the Flying A studio, took one look at Micky, with his angelic eyes and blonde curls, and his brother Pat, playing in their front garden, and hired them. Advised to move to Hollywood, Pat recalled: “We went overland in a big touring car and ended up renting a house on Vine Street. Mr Algiers rang up and said 'Mr DeMille is going to make another picture over at Lasky's, get your boys over there.'” Pat played the young Pharoah for DeMille in the 1923 Ten Commandments, and when DeMille suggested he adopt his mother's maiden name the rest of the family followed suit.

Micky appeared in DeMille's hit of 1922, Manslaughter, and played the apostle Mark in DeMille's King of Kings (1927) as well as a slew of other films. During the Depression, he was forced to work on fishing boats to make ends meet. Then he went to see DeMille and asked for work, not as an actor, but in the property department. DeMille assured him he would be assigned to his production – “a moment of exhilarating happiness and relief” Micky recalled; it was a turning point.

In 1933, he married his high-school sweetheart, Esther McNeil, and daughters Tricia and Sandy were born. After working on such outstanding productions as Henry Hathaway's Lives of a Bengal Lancer (1935) with Gary Cooper, DeMille's The Crusades (1935), and Frank Lloyd's Rulers of the Sea (1939) with Douglas Fairbanks Jr, Micky began sharing second unit work with Arthur Rosson on DeMille's Union Pacific (1939). It was a whole decade later that he was asked to become an assistant director – a highly complicated and responsible position but one he relished. And he was soon back with DeMille, a second assistant on Samson and Delilah (1949), a Biblical epic with Hedy Lamarr and Victor Mature.

DeMille had called him “Baby Moore'” since he first acted for him, and he continued to do so right up to the remake of The Ten Commandments in 1956. Micky took it on the chin. “I think he knew it kind of upset me just a little, but I never showed it. I just did what he said.”

Returning to second unit directing, Moore worked on Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), but he always said that his greatest challenge was Patton (1970), starring George C Scott. The second unit was huge and the director, Franklin Schaffner, assigned to it an unusually large number of scenes. “During the Second World War, I was not called up for duty,” Moore wrote. “However, I did feel I had been called to duty after shooting second unit on Patton.” Working in Almeria with more than 1,500 Spanish troops on the spectacular battle scenes, it was inevitable that accidents would occur. One involved a soldier being run over by a tank, after which he got to his feet, shaken but unhurt. “Times like these,” Moore wrote, “turned what little hair I had grey.” Moore himself was severely hurt himself on the production and it was several weeks before he could return to work.

In the 1980s he was hired on Steven Spielberg's Raiders of the Lost Ark. The films's executive producer George Lucas was highly impressed: “In shooting the truck chase, the storyboarded scene lacked context; there was no visual dynamic to really show the stakes as they were unfolding. Micky saw that from the outset and Steven gave him the liberty to make his own recommendations... Micky changed the location from an empty desert to narrow tree-lined streets… the results speak for themselves.”

As Spielberg put it “He saw round the corners of my imagination.” Moore explained: “If you are good, you shouldn't even be aware that a second-unit director has been involved. I just did the best I could possibly do on each shot, so they kept asking me to make more movies.”

When he was 95, Micky Moore wrote My Magic Carpet of Films (2009). His name should be added to the select group of “montage experts” – Slavko Vorkapich, Don Siegel and John Hoffman – for he displayed a similar sense of artistry.

His first wife died in 1992. In 1997, he married Laurie Abdo, who had been Howard W Koch's personal assistant at Paramount; she died in 2011.

Dennis Michael Sheffield (Michael D Moore), actor and director: born Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada 14 October 1914; married 1933 Esther McNeil (died 1992; two daughters), 1997 Laurice Abdo (died 2011); died Malibu, California 4 March 2013.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks