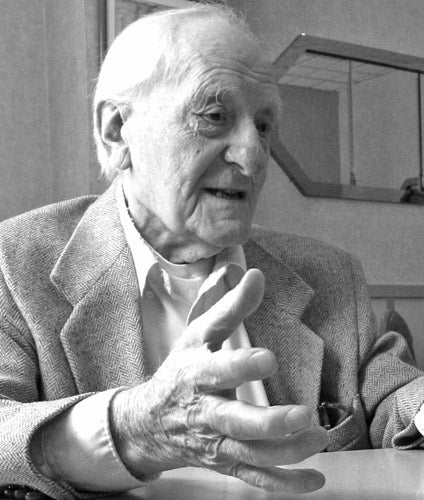

Michael Sayers: Writer whose career never recovered from being blacklisted in the United States

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Perhaps the last surviving link to the pre-war London literary scene, Michael Sayers, the Irish poet and playwright was a man of many parts. In the 1930s he was a protégé of TS Eliot and a friend of George Orwell, during the war an investigative reporter, after that a victim of McCarthyism, and in the 1960s a screenwriter for an early James Bond movie.

Born in Dublin, his parents were of Jewish Lithuanian extraction, his father a businessman with strong Republican sympathies. He was educated at Cheltenham College and Trinity College Dublin, where he was taught French by the young Samuel Beckett and mingled with actors such as Orson Welles and James Mason at Michael MacLiammoir's Gate Theatre. He published poetry, contributed to the theatre magazine Motley, went with a student drama group to the Soviet Union – which he found inspiring – and fell in love with a Russian girl.

In London he was taken up by TS Eliot, who asked him to review the theatre year for his literary magazine The Criterion, and by AR Orage, editor of The New English Weekly, who appointed him as a theatre reviewer. Orage introduced him to Rayner Heppenstall, the Weekly's drama critic, and suggested they share a flat with another of his reviewers, Eric Blair, who had recently adopted the pen-name "George Orwell". Sayers would often refer to him as "Eric Orwell", a man with two distinct identities.

For six months in 1935 they shared a flat at 50 Lawford Road, Kentish Town in London, but to Sayers and Heppenstall, Orwell seemed an odd fish with old-fashioned and low-brow literary tastes. While they preferred Yeats, Eliot and Pound, he preferred Housman and Kipling ("He used to rattle off Kipling like a barrel-organ," Sayers told me, "but he did it with great feeling.") And they were bewildered by his liking for detective stories and fascination with boys' comics, like The Gem and The Magnet, which he discussed endlessly.

Sayers enjoyed what he called a very gentle, affectionate and almost "homo-erotic" relationship with Orwell, but Heppenstall, a more volatile and provocative character, seemed to bring out his more savage side. One night, returning drunk, he provoked Orwell into attacking him with a shooting-stick and throwing him out. Afterwards he told Sayers, "Rayner's a fascist and an anti-Semite, and you would do well to avoid him in future," – advice the younger man followed, but later came to regret.

Sayers' literary career was progressing well. For The Criterion he reviewed plays by Eliot and Auden; for the New English Review Orwell's novels Burmese Days and A Clergyman's Daughter. From 1935, his stories appeared three years running in Edward O'Brien's annual Best British Short Stories. However, he had ambitions to work in the theatre, and in 1936 left for New York to be dramaturge to the stage designer and producer Norman Bel Geddes.

In 1938 he married Mentana Galleani, daughter of the militant Italian anarchist Luigi Galleani (whose followers included Sacco and Vanzetti), became radicalised, and then worked for Friday magazine, investigating Nazi-inspired efforts to keep America neutral. This resulted in three books written in collaboration with Albert E Kahn: Sabotage!: The Secret War Against America (1942); The Plot Against the Peace: A Warning to the Nation! (1945); and The Great Conspiracy in 1946. That year he flew to Europe for Fortune magazine, and was, he claimed, the first journalist to report on the newly liberated Nazi death camps, but his editor rejected the story as unbelievable.

Returning through London, he again met Orwell, who had just published Animal Farm. He found him profoundly depressed, about the recent loss of his wife and the advent of the atomic bomb – the frame of mind that led him to write Nineteen Eighty-Four. When Sayers spoke enthusiastically about Russia, Orwell told him, "We both started from the same place, but you went along the Stalin road and I went the opposite way. But if the Tories were in power I'd be just as much against them as you."

After the war, Sayers had a successful career with NBC, writing television plays starring the likes of Rex Harrison and Boris Karloff. But his wartime activities and Communist sympathies brought him to the attention of the House Un-American Activities Committee and he found himself blacklisted. Like many other banned artists, he left America to find work in Europe. Denied a US visa, he was offered an Irish passport by Conor Cruise O'Brien, and from near Cork and later from France, writing under the pseudonym Michael Conners, he contributed plays to BBC television's Armchair Theatre and drama series such as Robin Hood, William Tell and Ivanhoe. In London he introduced another blacklisted expatriate, Joseph Losey, to Dirk Bogarde, an introduction which led to Bogarde's appearing in several Losey films, including The Servant and Accident.

His American passport was renewed when Charles K Feldman invited him to Hollywood to work on the screenplay of the Bond movie Casino Royale, a film he preferred to forget, and he was involved at early stages in developing a script for the musical Hair. Later he wrote plays, taught screenwriting and encouraged young artists and film-makers in New York until shortly before his death.

Sayers had a sharp political intelligence and spoke of his persecution in America with realism and resignation. He was a gentle, humorous man, who, like many gifted writers of his generation, paid the price for having the wrong opinions at the wrong time in the wrong place, and whose career never quite recovered from the set-back.

Gordon Bowker

Michael Sayers, writer: born Dublin 19 December 1911; married firstly Mentana Galleani (divorced 1955; two sons, one adopted son); 1957 Sylvia Thumin (died 2006); died New York 2 May 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments