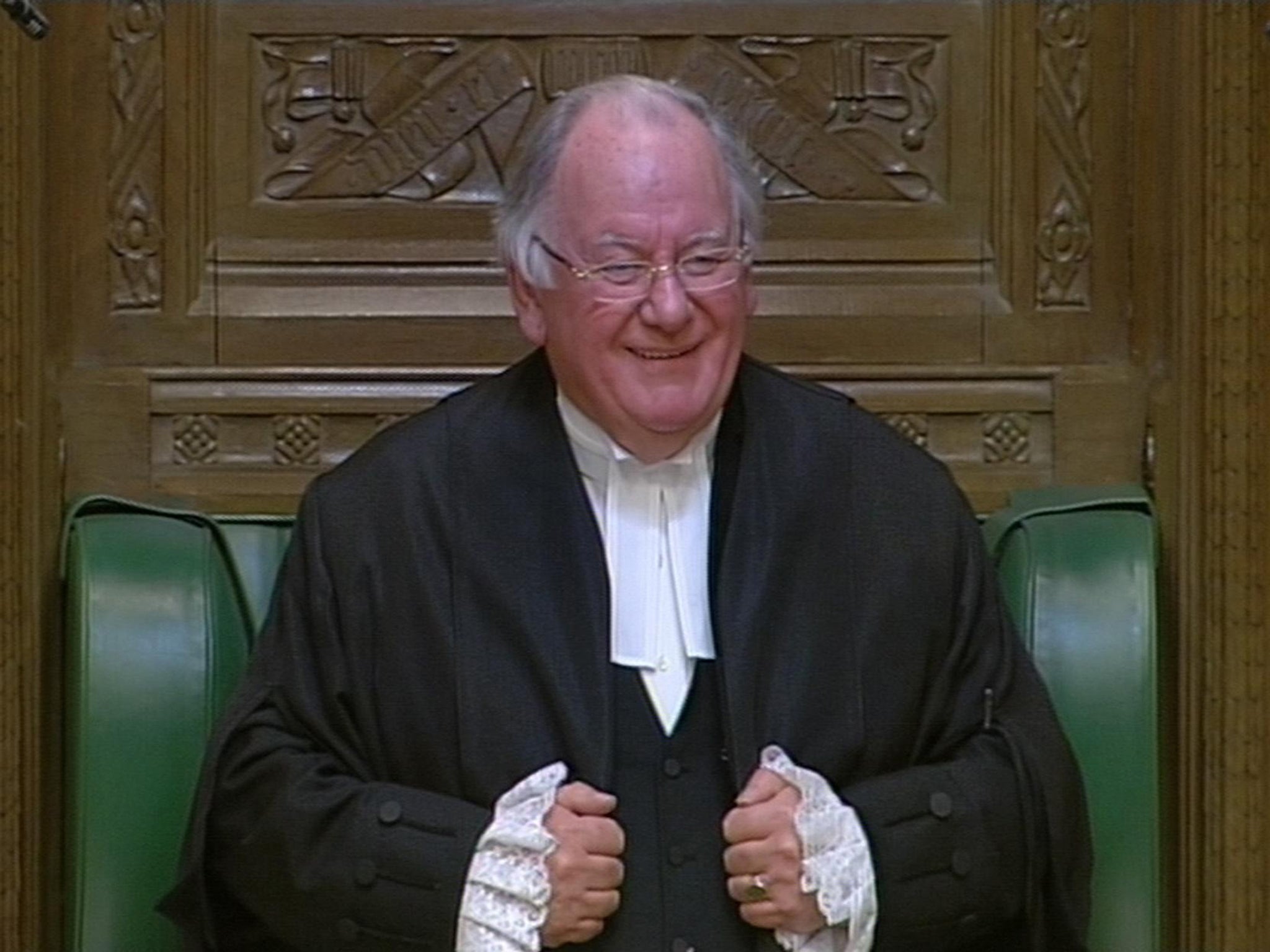

Michael Martin remembered: The first Commons speaker to be ejected from parliament in 300 years

The former sheet metal worker who became a Labour MP and peer failed to tackle the MPs’ expenses scandal of 2009 in a way that might quell public anger

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.That a sheet metalworker should have metamorphosed into a speaker of the House of Commons was a remarkable achievement. Whether Michael Martin was an alpha, beta or gamma occupant of the chair is a matter of diverse opinion.

I can only say that, as father of the House for more than half of Martin’s tenure, and having served under Harry Hilton-Foster (B++), Horace King (gamma), Selwyn Lloyd (alpha), George Thomas (B–), Bernard Weatherill (A–), Betty Boothroyd (A+ as a speaker, B++ as a public persona), I would award Martin an A–.

As a colleague, he was both kind and authoritative; his decisions displayed generally good judgement; his woes began in earnest after I retired, and centred on a perceived (wrongly in my view) indulgence over MPs’ allowances.

After the notorious Derek Conway case (the Conservative MP who was at the heart of the MPs’ expenses scandal in 2009 when it emerged that he had employed his sons as researchers), it was felt that somehow Martin was not the right person to cope with the aftermath of a situation, simmering for some time but brought to a head by the blatant misbehaviour of a member paying an allowance to his sons who, it transpired, had not lifted a proverbial finger to do any work.

This put Martin under great strain; my first speaker, Harry Hilton-Foster, died of a heart attack in office and ever since then I have been under no illusion about the strains that can accumulate for a person in a very lonely job.

“Air Miles Martin” – he was supposed to have taken his family on accumulated air miles to be with him in London over Christmas and the New Year – was a wounding soubriquet.

But what really began to fester were repeated bad relations with senior personages of the Commons staff. We never quite understood why he had got rid of the admirable Sir Nicholas Bevan, who had served Betty Boothroyd so well in the pivotal position of Speaker’s Secretary.

Then there was the row about him getting rid of his diary secretary on the grounds that she was “too posh” (I happen to know that there was more than one side to this story). But the fact is that a lot of MPs, not only Tories, felt that chippiness about class came into the equation.

Martin was proud of being working class; but as an Old Etonian, who first knew Martin when he was a shop steward at Rolls Royce in 1972, I would acquit him of any trace of class resentment, as such. The epithet “Gorbals Mick” was an ill-judged, unjustified, nasty invention of certain metropolitan sketch-writers.

These frivolous but widely read sketch-writers had a grudge against Martin from the very beginning; he had been chairman of the Commons committee years before that had excluded them from the privilege of sauntering on to the terrace of the House of Commons, other than in the company of an elected MP.

Moreover, had Martin been ill at ease with people of a background different to his own, he would not have been chosen as a Committee chairman, still less as deputy speaker or previously, in 1970, by Denis Healey, then deputy leader of the Labour Party, as his parliamentary private secretary. In April 2008, Healey told me from his home at Alfriston in Sussex: “I found Michael Martin to be both sensible and loyal and a man of sincere views in helping others. He was also a brave politician when the chips were down. I am sorry that he is going through such a torrid time as speaker of the House of Commons; the Michael Martin that I know does not deserve the kind of abuse which he has had.”

Martin was born in the Anderston district of Glasgow, one of the five children of a merchant navy stoker and a cleaning lady. He always told me that the “Gorbals” tag irritated him because, he said with a twinkle, that Anderston made the Gorbals look like Weybridge and “most of my friends would have considered living there in the Gorbals a step up”.

He told me that he had been very unsatisfactory pupil at St Patrick’s, a huge Roman Catholic secondary school in Glasgow, and left with not even the most rudimentary of qualifications. But fortunately he managed to get a job as an apprentice train repairer at the St Rollox Works in Springburn, with its history of supplying railway engines to the empire, and from there a job as a sheet metalworker for Rolls Royce.

I was told by one of his contemporaries at Rolls Royce that actually he became, as a quick learner, a very skilled and useful member of the squad. It was Rolls Royce which gave him a certain self-esteem since his father, a merchant navy stoker who had been torpedoed five times in the war, had separated from his mother. The lad who would one day occupy the great rooms of the speaker’s apartment in the Palace of Westminster was reared in a crowded Glasgow tenement, as he used to tell us dodging through the washing lines, and coming home to spuds and dripping for high tea. As an apprentice sheet metalworker, he became active in the Amalgamated Union of Engineering Workers.

He was poached in 1976 by another union, the National Union of Public Employees, as a full-time organiser, but he kept his lines of friendship with the AEU open and was chosen by them as their candidate in Glasgow Springburn, where they weighed the Labour majority of more than 14,000 (had he not transferred to another union, he realised that he would have been ineligible as a full-time official to be selected first of all as a councillor and secondly as a prospective member of parliament). He was always very streetwise.

When he first arrived in the House of Commons it was thought that he was a plodder for although he worked hard and served on various committees, his very broad Glasgow accent made oratory difficult and he was not considered as ministerial material. A devout Roman Catholic (he became the first Catholic speaker since the Reformation), by his vote he was unfashionably socially conservative, opposing moves to liberalise the abortion laws and voting, only one of half a dozen Labour MPs to do so, against the proposal to lower the homosexual age of consent to 16.

He made his maiden speech on 17 May 1979. “At one time Springburn had a thriving railway industry which produced steam locomotives. In fact, Springburn made more than half the number of steam locomotives produced in the world. Many of them are still in use in Africa, India and South America. The industry not only employed thousands of skilled and semi-skilled workers but provided work for the smaller firms in the area. I am convinced that had the private railway companies ploughed their profits back into the industry, Springburn would not have the unemployment problem that it has today.”

The centre of Martin’s early political interest was to get his government to recognise the need to strengthen the Scottish Development Agency so that it could bring new industry to Glasgow.

His area needed industrial revitalisation to prevent it from becoming, as he put it, “an industrial graveyard”. His chance came when he was to be chosen as a junior member of the chairmen’s panel – which means presiding over standing committees of the House of Commons. He cut his teeth on that extraordinary body, the Scottish Grand Committee, and proved to be an unexpected success in controlling some longwinded and obstreperous members of parliament in what was frankly an ornamental and not very important part of the House of Commons. With a growing reputation for competence and fairness in the chair he became acceptable both to Labour and Tories as first deputy chairman of Ways and Means.

No one envisaged him at that stage as a possible speaker. The fact that he succeeded to the chair in the year 2000 was due to a number of unusual factors.

In particular, the Conservatives thought that it was their turn since the previous speaker had been the internationally successful as a public persona and representative of Westminster Betty Boothroyd.

However, the Tory leadership put forward as their preferred candidate not their own deputy speaker Sir Alan Haselhurst but Sir George Young. This irritated a huge swathe of the Labour Party, including me. Some of us thought that Young would prove to be too much of a martinet but what really stuck in our gullet was the fact that Young had been Margaret Thatcher’s creature as a junior minister who had sledge-hammered through the denationalisation of the railways, which we considered to be particularly disastrous.

As soon as Young was chosen by the Tories, we turned to Martin – and by the time other Tories, including Haselhurst, had been put forward it was too late; Martin was dragged in age-old fashion to the chair.

Even so, there has been a good deal of controversy. He had declined to take part in Hustings meetings with other candidates. He told me and others: “There is no need for me to do any Hustings meetings – my canvassing was done over years in quiet conversations in the tea room.” It was indeed true that almost every night, when he was waiting for duty in the chair, he would drift in and chat to people like me. And very convivial he was too, because he had an earthy, though strictly non-swearing, non-blue, non-bad language sense of humour. He proved to be a man of many interests, not least his stories about relaxing with a blast of the bagpipes. He was in fact a useful member of various pipe bands.

Martin’s real troubles began after I ceased to be a member of parliament, having retired at the 2005 general election. I listened on the radio to the Prime Minister’s Questions in which he said: “Th’ Prame Ministar is hair to talk aboot the business of gooverment.”

Actually, I thought he was only carrying out the rules under Erskine May, the rulebook of the House of Commons. The Tories bellowed in protests while even Labour MPs seemed to be incredulous. On what basis, they wondered, could a change of prime minister – that was the subject under discussion – not be considered the business of government? (The fact is that his great predecessors, Selwyn Lloyd and Bernard Weatherill, would have taken the same attitude.)

In January 2008 my wife, as great-niece of John Wheatley, the first Labour government housing minister and father of the council house, was asked to open the new wing of the John Wheatley College in east Glasgow. Since it was bang in the middle of Martin’s constituency, he came, as he put it, “the supporting speaker” – a nice line in self-deprecation, which people found rather attractive.

Seeing him among “his ’ain folk”, where he was hugely popular, explains some of his vexation. He poured out his heart to me, his old friend. He said that he was deeply critical not only of David Cameron and George Osborne but of a number of the Labour cabinet, particularly David Miliband and Ed Balls. “What do they know about life? They behave like children, not cabinet ministers.” Martin’s difficulties, such as they became, were more related to generation than to class resentment.

A year later he earned the unfortunate distinction of becoming the first person to resign the post of speaker of the House of Commons in 300 years, over the MPs’ expenses scandal to which he gave a stumbling response.

He had called for sources of the leak to The Daily Telegraph, which had broken the story, to be investigated, casting the focus on the newspaper rather than MPs – not what the public expected from the speaker.

He did not budge easily. MPs broke centuries of protocol and engaged with arguments with the speaker, asking him to leave – eventually a motion was tabled signed by 23 MPs and he did for the sake of “unity”.

Despite calls from peers from him to become the first speaker to be denied an automatic on retirement place in the House of Lords – none after all had been forced out – he entered the Lords as Baron Martin of Springburn in 2009.

Michael John Martin, Baron Martin of Springburn, born 3 July 1945, died 29 April 2018

Tam Dalyell died in 2017. This obituary has been updated

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments