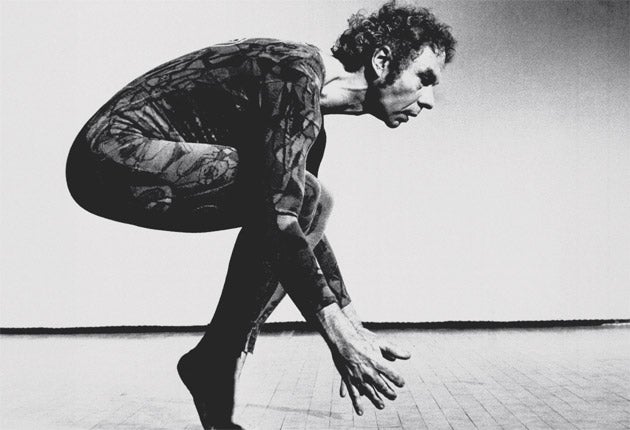

Merce Cunningham: Inspired choreographer who laid the foundations for modern dance

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The choreographer Merce Cunningham was undoubtedly the greatest single influence on contemporary dance both in Britain and in the US. His originality lay not only in his well-known use of chance procedures and of choreography conceived independently of music and decor, but in his expansion of the basic possibilities of space, time and movement in dance. A prolific genius for whom the wells of creativity seemed to flow unhindered, he has left a unique legacy, full of urban dynamism and the kaleidoscopic imagery of city streets, natural processes and animals – and at the same time of an overarching classical clarity, dignity and virtuosity.

His peaceful death at home in Manhattan, aged 90, was announced by the Cunningham Dance Foundation.

In 1964, the company's month-long London season, the first of many here, was a success that, together with the first Martha Graham season the previous year, served as impetus toward a British contemporary dance movement. The headline of a review by Alexander Bland in The Observer announced, "The Future Bursts In". That London season, along with the rest of the world tour that followed, also helped gain acceptance for Cunningham's work at home in New York. Britain honoured him with a 1985 Laurence Olivier Award for one of his dances, Pictures, and the 1990 Digital Dance Premier Award, which he used for the creation of Touchbase for the Rambert Dance Company, long a home to his work.

Like George Balanchine, Cunningham was a pioneer of so-called abstract dance, putting faith in the power of unadorned movement to be expressive. He imbued each work with its own atmosphere, sometimes simply through the questions, often of a formal nature, that he posed himself.

Some of Cunningham's works, however, seem to have a particularly strong atmosphere. He has said that certain ones owe something to his roots in the American Pacific Northwest, where he grew up – pieces such as RainForest, or Inlets, with its misty, timeless quality recalling lush forests (it has decor by the distinguished northwestern painter Morris Graves). Beach Birds for Camera refers to a coastal source of movement inspiration. He also felt that growing up in the Pacific Northwest, with its large Asian population, inclined him to feel at home with Eastern philosophies.

Cunningham studied tap dance in his native Centralia, Washington, and an eclectic variety of other forms, which gave him a typically American flexibility of approach. An important influence was the respected Cornish Institute of Allied Arts in Seattle, where his studies included Graham technique with Bonnie Bird (who subsequently played a major role in London's Laban Centre for Movement and Dance). At the Cornish Institute he met John Cage, whose revolutionary musical theories, including the use of chance operations and taste for Eastern philosophical thinking, were to be lasting inspirations to Cunningham. The two were to become life partners as well as collaborators. In 1981 they co-directed the International Dance Course for Professional Choreographers and Composers at the University of Surrey. Cage was music director of the Cunningham company until his death in 1992.

Beginning in the Graham company, of which he was a member from 1939 to 1945, Cunningham made an indelible impression as a dancer. Slender as a young Picasso saltimbanque, he had a remarkable light jump, an excellent sense of rhythm (which was to remain a quality of his own choreography, despite its lack of relation to any rhythmic musical accompaniment), and a lyrical, Apollonian quality. This Apollonian grace served in Graham's choreography as a contrast to the dark, brooding, Dionysian presence of her other early male star, Erick Hawkins.

For a time, Cunningham attended classes at Balanchine's School of American Ballet, on an unusual piece of advice from the usually partisan Graham. While Graham's use of the contraction was to be the point of departure for Cunningham's remarkable elaboration of inflections of the spine, ballet was also to contribute to Cunningham technique, especially in the varied articulations of the legs. The resulting combination of torso and legs opened up rich possibilities for a complex, sophisticated use of highly trained dancers.

Cunningham gave his first concert in 1944, in collaboration with Cage. "I started with the idea," he said later, "that any kind of movement could be used as dance movement, that there was no limit in that sense. Then I went on to the idea that each dance should be different. That is, what you find for each dance as movement should be different from what you had used in previous dances." His use of chance procedures, sometimes misunderstood as a licence for chaos, was in fact a carefully ordered method of going beyond his own innate way of moving. The choreography in most cases became fixed.

Cunningham drew inspiration from the practices and conversation of contemporary visual artists. As in much modern art, he concentrated on the materials of the form rather than on representation. His non-hierarchical use of space, in which all parts of the stage are equally important, has been compared to Abstract Expressionism.

Visual artists were among the earliest supporters of his work. Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns served as long-term artistic advisors to his company, while its designers included Richard Lippold, David Hare, Frank Stella and Andy Warhol. Marcel Duchamps, whom Cunningham greatly admired, agreed for some of his work to be adapted as decor for Walkaround Time.

The absence of hierarchy in Cunningham's use of the performing space, in contrast to ballet's emphasis on symmetry and centre stage, was echoed in other aspects of his dances as well: the lack of a rigidly controlling front view, so that simultaneous views of the same motif were possible, as in cubism; the absence of a time progression leading to a climax, but on the contrary the possible simultaneity of equal events; the openness of expression that observers were free to interpret for themselves; the lack of a hierarchy among the dancers. The dancers in his works, with their erect and alert demeanour, moreover, give an impression of quick intelligence and independent decision-making.

No wonder, then, that on international tours observers sometimes found, without conscious intent on Cunningham's part, a political message, "because," as he explained, "in a sense we are dealing with a different idea about how people can exist together. How you can get along in life, so to speak, and do what you need to do, and at the same time not kick somebody else down in order to do it."

The affinities of Cunningham's work to contemporary scientific and technological thinking are clear in his sophisticated use of film and video and conversely, the cinematic quality of his stage choreography with its use of cutting, fragmenting and layering of time and space. In the 1990s, Cunningham pioneered the use of a computer program called Life Forms in choreographing, as a supplement to working with live dancers. It allowed him to manipulate three-dimensional figures onscreen, thereby contributing to his varied and continuing creativity, with its agility making up for Cunningham's own increasing stiffness from arthritis. He also used digital imagery in performance, on scrims, in Biped (1999) and Fluid Canvas (2002) with the help of the animation technique of motion capture technology.

His works have been danced by other companies, including the New York City Ballet, American Ballet Theatre, the Paris Opera Ballet and France's Theatre du Silence, and he has collaborated on a number of books. Among his many honours, in addition to the British awards, were Chevalier de la Legion d'Honneur, Kennedy Center Honors, National Medal of Arts, Italy's Porselli Prize, and New York City's Handel Medallion.

In later years, in spite of his arthritis, he continued to create small appearances for himself in some of his dances: an avuncular presence hovering over his eternally young dancers in a relationship sometimes humorous, always poignant and, it was often noted, of an implicit drama.

Cunningham's ninetieth birthday was celebrated this spring with the premiere of Nearly Ninety.

Allusions to death were remarked upon in some later works, especially after John Cage's death, as in the 1995 Ground Level Overlay. In the 1993 Doubletoss, the dancers alternate in the roles of those who, wearing angel-like, flowing black netting, support others dressed in everyday clothing. It suggests the continuing, nourishing presence of those who have gone before – a comforting and apt thought from one who gave and will continue to give so much inspiration.

Marilyn Hunt

Merce Cunningham, dancer, choreographer, teacher, company director: born Centralia, Washington 16 April 1919; died New York City, 26 July 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments