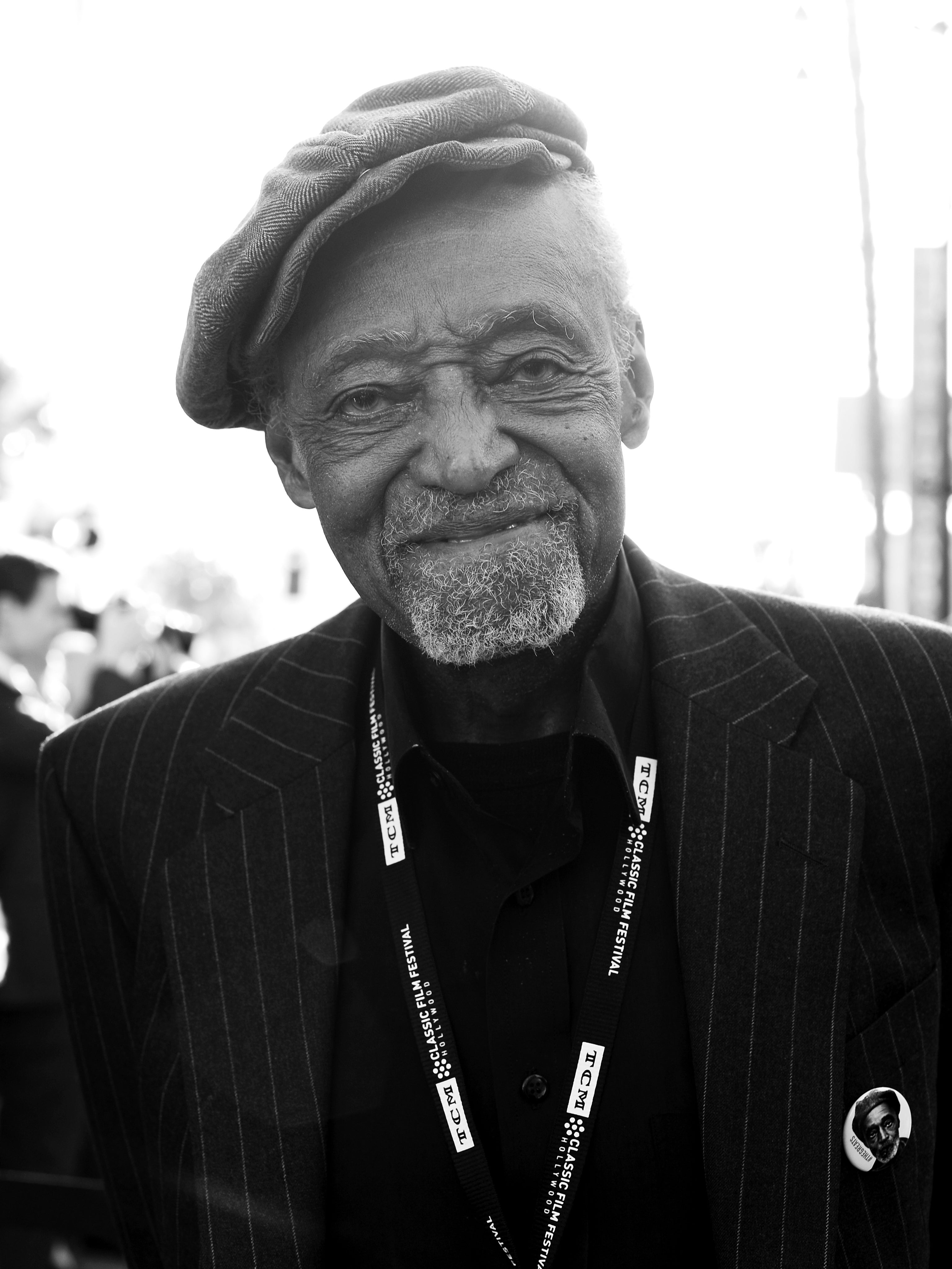

Melvin Van Peebles: Godfather of black cinema and pioneering filmmaker

The multi-faceted director’s low-budget 1971 phenomenon, ‘Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song’, proved a milestone of independent and African American cinema

Melvin Van Peebles, whose low-budget 1971 phenomenon, Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song – an X-rated film about a Black revolutionary’s survival on the run – proved a milestone of independent and African American cinema, has died aged 89.

Over a six-decade career, Van Peebles continually reinvented himself: as an air force officer, a cable-car gripman, a novelist in English and French, a Tony Award-nominated playwright and composer, an Emmy Award-winning TV writer, a spoken-word artist, and, for a spell in the 1980s, the only Black floor trader on the American Stock Exchange.

Throughout his life, Van Peebles was propelled and defined by his boundless self-confidence and bravado. As a young man – lacking money, connections and institutional support – he practically willed himself into recognition as a visual artist.

His legacy rested largely on Sweetback, for which he served as writer, director, producer, composer, stuntman and star. After finding no other Black actor in Hollywood willing to risk his image on such a role, he cast himself as the title character – a sex-show stud who beats up two racist police officers and spends the rest of the film politically radicalised, an unlikely hero on a righteous odyssey.

Made on a shoestring budget of $500,000, Sweetback opened in two Black-neighbourhood theatres, one in Detroit and the other in Atlanta. It quickly set box-office records and expanded its reach to other theatres, grossing more than $10m that year on its way to becoming one of the most lucrative independent films in history.

Van Peebles attributed the film’s success to his belief that he could surmount any obstacle with hustle and ingenuity.

He said that when he couldn’t obtain financing for the film, he bluffed a bank into giving him a large line of credit and borrowed $50,000 from actor-comedian Bill Cosby. To avoid paying union wages, he told the trade guilds that he was making a fast, cheap porno that wasn’t worth their time. Then he shot the 97-minute film in Los Angeles in just 20 days.

When the Motion Picture Association of America gave Sweetback an X rating, Van Peebles enticed his target Black audience with movie posters and other advertisements that proclaimed the film “RATED X BY AN ALL-WHITE JURY”.

He persuaded Black DJs to promote Sweetback, which was dedicated “to all the Brothers and Sisters who had enough of The Man”. He said the Black Panther Party endorsed it as “required viewing,” and Black Panther co-founder Huey Newton called it “the first truly revolutionary Black film” because its brazen hero gets away with roughing up the police.

Civil rights activist and former NAACP chairman Julian Bond told The New York Times in 2002 that watching Sweetback, “was just like, ‘Wow!’ You’d just never seen anything like it before ... You’d never seen a black guy beat up the police and get away.”

Sweetback was what he called a “take-no-prisoners political manifesto” made expressly for a Black audience, from the stick-it-to-the-Man imagery to the funky title. “In ‘whitese,’” Van Peebles joked to Newsday, “it would be called ‘The Ballad of the Indomitable Sweetback.’”

To critics, Van Peebles’s reputation teeters on a cultural precipice. He was hailed by some as a filmmaking pioneer with boundless imagination and derided by others as a misogynist with a shaky camera, odd lighting choices and storytelling techniques that were more exuberant than coherent. (He called polished production values the stuff of “technical colonisation” imposed by White Hollywood executives.)

Donald Bogle, a film historian and scholar of the depiction of Black people on-screen, told The New York Times in 1973 that Sweetback was a rejoinder to the long tradition of films in which African American performers were relegated to servile roles or used for comic relief.

For all the attention that Van Peebles received, he struggled to parlay his celebrity – or notoriety – into further directorial success. At least one of his films was shelved for lack of interest by distributors, and he was replaced as director of the Richard Pryor film Greased Lightning (1977) after clashing with producers.

“If you’re smart and White, you’re considered a shrewd businessman,” Van Peebles told The New York Times. “If you’re Black, you’re considered a militant troublemaker. In the eyes of the Hollywood establishment, I was the character of Sweetback.”

Meanwhile, Van Peebles had gained recognition for his music, including the 1969 album Brer Soul, a collection of jazzy-funk song-poems. He ploughed profits from Sweetback into two Broadway musicals for which he wrote the book, music and lyrics: Ain’t Supposed to Die a Natural Death (1971), featuring musical vignettes set in a Black ghetto, and Don’t Play Us Cheap! (1972), about a Harlem house party disrupted by the Devil’s minions.

The plays, which drew mixed reviews, earned Tony nominations for best book, and Van Peebles received a nomination for best original score for Ain't Supposed to Die. With his film prospects at a nadir, he pivoted to writing books and teleplays.

He also spent about five years working for Wall Street brokerage houses. This unlikely turn came after he made a wager with a friend, a prominent dealer in precious metals, over the return on a real estate deal. Under the terms of the bet, when Van Peebles lost, he had to go to work as a floor trader. He wrote a primer, Bold Money: A New Way to Play the Options Market (1986), in which he likened market speculation to Atlantic City games of chance.

Melvin Van Peebles – Van was his middle name at birth – was born on Chicago’s South Side on 21 August 1932.

He said his father, who owned a tailor shop in a rough neighbourhood, put him to work at the store at 10 and taught him to fend for himself on the street, selling unclaimed clothes for a percentage of the profits. His mother, meanwhile, encouraged his burgeoning interest in art history, hoping that he would be the first in the family to attend college.

He received a bachelor’s degree in English literature from Ohio Wesleyan University in 1953. As a student, he was enrolled in the air force Reserve Officer Training Corps, and after graduation, he spent three years as a flight navigator. He married Maria Marx, a White college classmate (“I figured someone should get all the dough the air force would pay if I died”), and struggled as a painter in Mexico before settling in San Francisco.

In 1959, he packed up his family – which included two children, Mario and Megan – and, on the GI Bill, enrolled at a university in the Netherlands to study astronomy. As his marriage and finances disintegrated, he moved alone to Paris and supported himself as a gigolo while contributing to the satirical anarchist magazine Hara-Kiri.

After Van Peebles learned that the French government had a policy of supporting authors who wanted to film their own work, he wrote novels and applied for a director’s license and the grants that would come with it.

With a Gallic shrug, a bureaucrat passed him a director’s card, and he turned one of his books, La Permission, into his debut feature, The Story of a Three-Day Pass (1968), about a bittersweet affair between a Black American soldier and a White Frenchwoman.

Its jumpy editing style, then in vogue among French New Wave directors, helped it become the official French entry at the San Francisco Film Festival. Three-Day Pass won support from such influential reviewers as Judith Crist.

“My film became the critics’ choice at the festival, but they didn’t know I was an American, let alone Black, and that created a furore, because there were no Black directors in the States,” Van Peebles later told the trade publication Billboard.

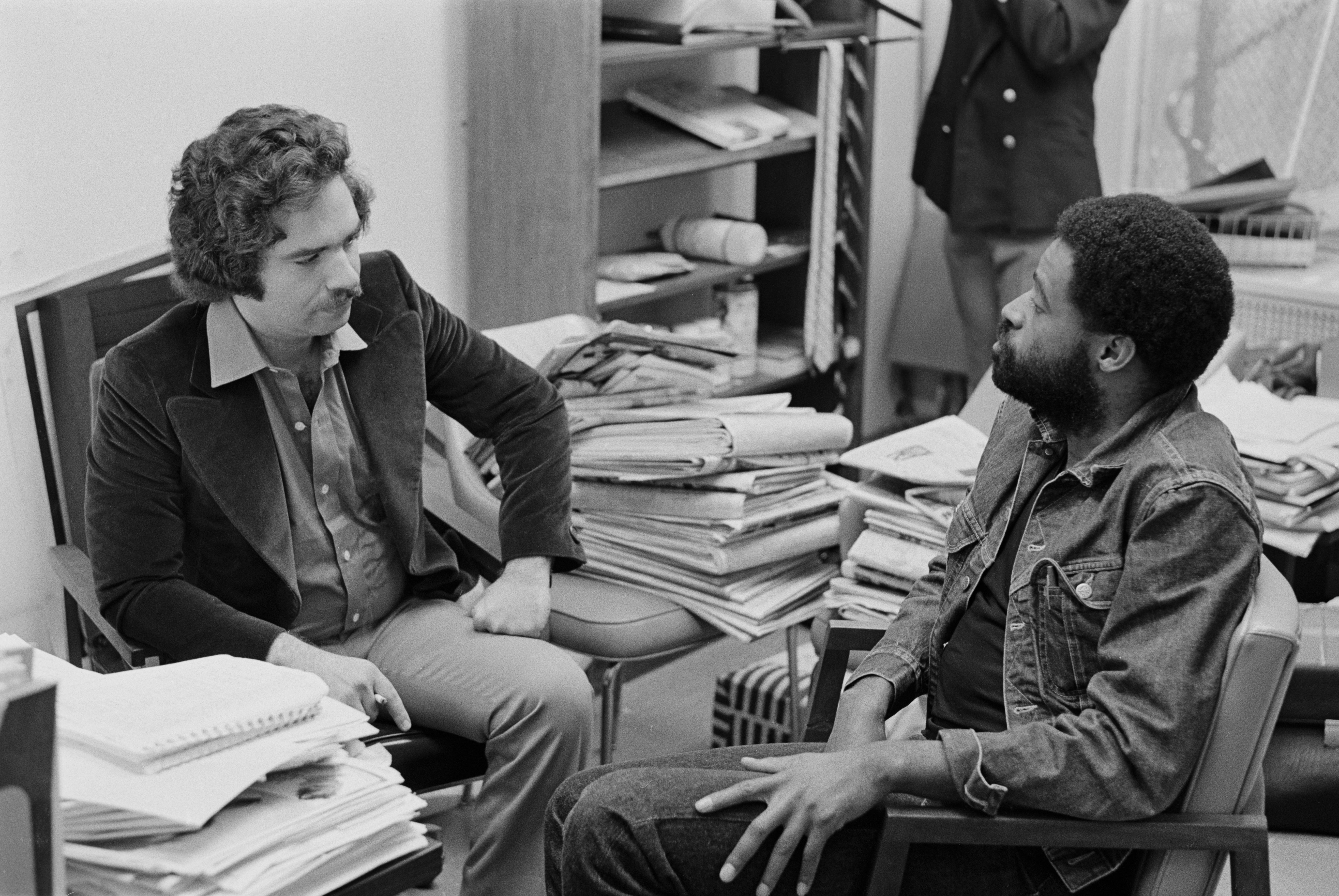

Van Peebles landed a contract with Columbia Pictures to direct Watermelon Man (1970), a Herman Raucher-written satire about a bigoted White insurance salesman who wakes one morning to find that he is Black. Van Peebles said studio executives wanted a White movie star to play the role in blackface but that he persuaded them to use Black comedian Godfrey Cambridge in whiteface.

“Three-quarters of the film the guy is Black,” he told The New York Times. “I said, ‘Let’s have a Black guy in whiteface.’ Their reaction was, ‘Is that possible?’ The king can play a valet but can the valet play a king? They didn’t understand the racist implication of this question.”

Watermelon Man drew scathing reviews for its haphazard blending of rage and puerile comedy. Van Peebles told The Washington Post that he took the job mainly for the $70,000 compensation, which helped him finance Sweetback.

As he continued his wide-ranging career, Van Peebles directed the music video for the Whodini song “Funky Beat” (1986). He collected an Emmy for outstanding writing in a children’s special for the CBS drama The Day They Came to Arrest the Book (1987), based on Nat Hentoff’s novel about the banning of Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn at a high school.

His daughter, Megan Van Peebles, died in 2006. In addition to his son, Mario, survivors include two other children and 11 grandchildren.

Van Peebles also wrote and narrated the documentary Classified X (1998), a rumination on his quest for authenticity in an industry – and a world – where Black consciousness “had been colonised by images of Black humiliation, marginality, subservience, impotence and criminality that are ubiquitous in mainstream American cinema”.

Sweetback struck like a lightning bolt, he said, because it “didn’t owe its allegiance to anything in the past”.

Melvin Van Peebles, actor, filmmaker, novelist and composer, born 21 August 1932, died 21 September 2021

© The Washington Post

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks