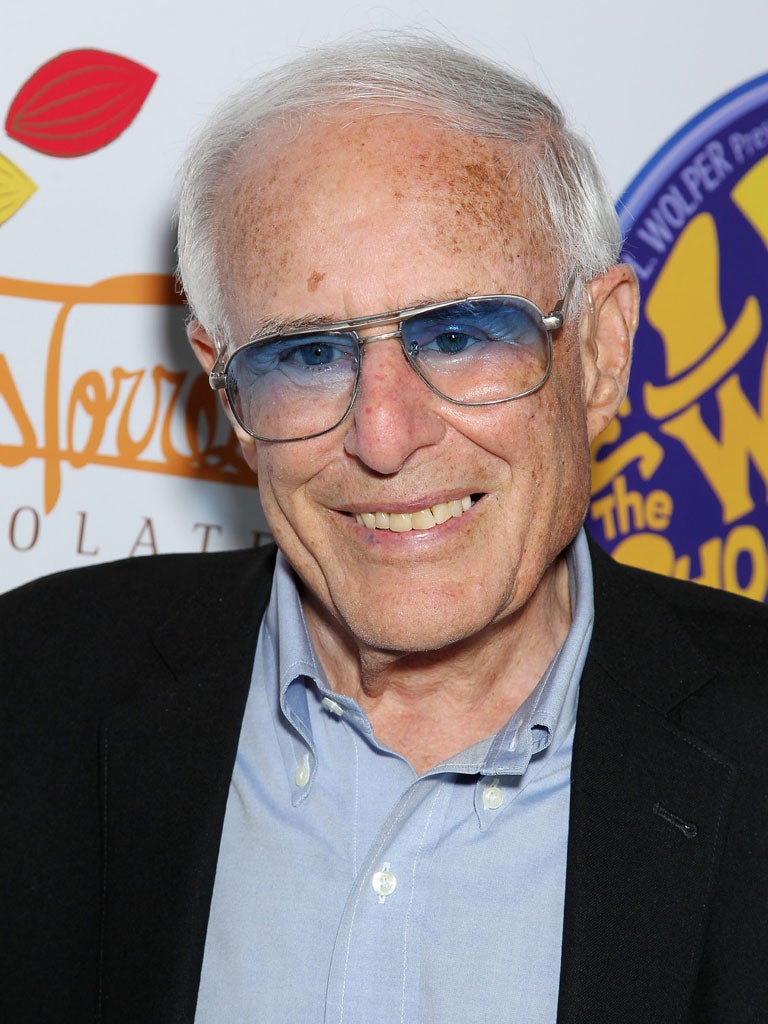

Mel Stuart: Director behind Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory

Stuart's film take on Dahl was not initially a success; it was only later that the public gave it popularity

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The largest part of Mel Stuart's prodigious output as a film director and producer was in documentary, where he won several Emmys and was Oscar-nominated; but his best-known venture was the musical-fantasy Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory (1971). Stuart's daughter Madeleine adored Roald Dahl's Charlie and the Chocolate Factory – and begged her father to film it. She was rewarded with a tiny role, while her brother David played the bigger role of Winkelmann. Dahl found it difficult to rethink the story cinematically, and though he was credited with the screenplay, it was largely the work of David Seltzer. Dahl later disowned it and refused to release the film rights to the sequel, Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator.

In the first edition of the book, Wonka's workers, the Oompa-Loompas, were black pygmies, but subsequent editions changed them to blondes – and in the film they were orange with green hair. Stuart also claimed that he changed the title when he was told that the name Charlie was associated with plantation owners, though he felt his title sounded better in any case. However, it may have had more to do with the fact that the film was funded by the Quaker Oats Company, who were making the tie-in Wonka Bar, though it was later licenced to Nestlé.

Though Gene Wilder was far from first choice to play Wonka (Dahl initially wanted Spike Milligan, then Ron Moody), he brilliantly captures the character's ambiguity – warm and yet unsettling. He insisted on his bizarre entrance, in which he gradually loses an affected limp via a forward roll, so that the audience can never be entirely sure if he is telling the truth. Stuart accepted the idea, but filmed a "straight" entrance as well, just in case. Fortunately, the studio preferred Wilder's version. Nevertheless, the film was not a success: Variety thought it "okay", but (not entirely unfairly) found Wonka himself "cynical and sadistic". It was only later that the public gave it its popularity.

Stuart was the son of a hat-store-owning history fan. When and why he changed his name from Stuart Solomon isn't clear. He intended to become a composer, but after New York University he ended up working for an advertising agency. There he met Mary Ellen Bute, who was working on a series of experimental animated films set to classical music. In the late 1950s, after assisting her, he became a film researcher on CBS's epic series The Twentieth Century, which was fronted by Walter Cronkite.

In 1959 David L Wolper invited Stuart to join him as a documentary producer. He stayed until 1977, when he set up on his own. Stuart made around 180 films, often on the arts, history and the US Presidency. Notable subjects tackled in 1962 alone included writer Ray Bradbury, controversial New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, Hollywood: the Fabulous Era and D-Day, June 6, 1944.

Stuart found the Kennedy era particularly fascinating and based two Emmy-winning films on Theodore H White's books The Making of the President, 1960 (1963) and, six years later, The Making of the President, 1968. JFK's assassination was the subject of the Oscar-nominated Four Days in November (1964); and The Journey of Robert F Kennedy charted his brother's life. In 1978 Stuart returned to the era with the TV movie Ruby and Oswald, starring Michael Lerner and Frederic Forrest. Theodore White also wrote the Emmy-winning hardline Cold War documentary China: the Roots of Madness (1967).

Stuart was Emmy-nominated for Life Goes to the Movies (1976), critic Richard Schickel's study of Hollywood in the middle of the 20th century, and Man Ray: Prophet of the Avant-Garde (1997). As a producer, he gave William Friedkin his first credits before he moved from documentary into fiction.

Wattstax (1973) mixed street interviews and Stax Records' concert for the Watts riots to examine a tense moment in US race relations, and garnered a Golden Globe nomination.

Stuart's other fiction films include the comedy If It's Tuesday, This Must Be Belgium (1969), in which Ian McShane plays a guide with a girl in every city, leading a whirlwind European bus tour for American tourists. The following year's more serious I Love My Wife starred Elliott Gould as a surgeon who, despite a successful career and happy marriage, embarks on a series of ennui-fuelled affairs. In the equally serious One is a Lonely Number (1972), a young woman comes to terms with divorce from a man she later discovers was unfaithful. The TV movie Bill (1981) starred Mickey Rooney as a man who is released from many years in an asylum to live with a kindly family. Three-times Golden Globes-nominated, it picked up trophies for script and Rooney himself.

Stuart gradually returned to documentary via fact-based dramas such as The Triangle Factory Fire Scandal (1979), about a 1911 New York fire that led to improved health and safety legislation. After occasional episodic drama, including 1983's ill-fated Casablanca TV series with David Soul, and the pioneer-family drama series The Chisholms, he returned to documentary proper with films on famous poets, natural history and cinema.

Mel Stuart (Stuart Solomon), film director and producer: born Manhattan 2 September 1928; married first 1956 Harriet Rosalind Dolin (divorced, three children); second Roberta Silberman (died 2011); died Beverly Hills 9 August 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments