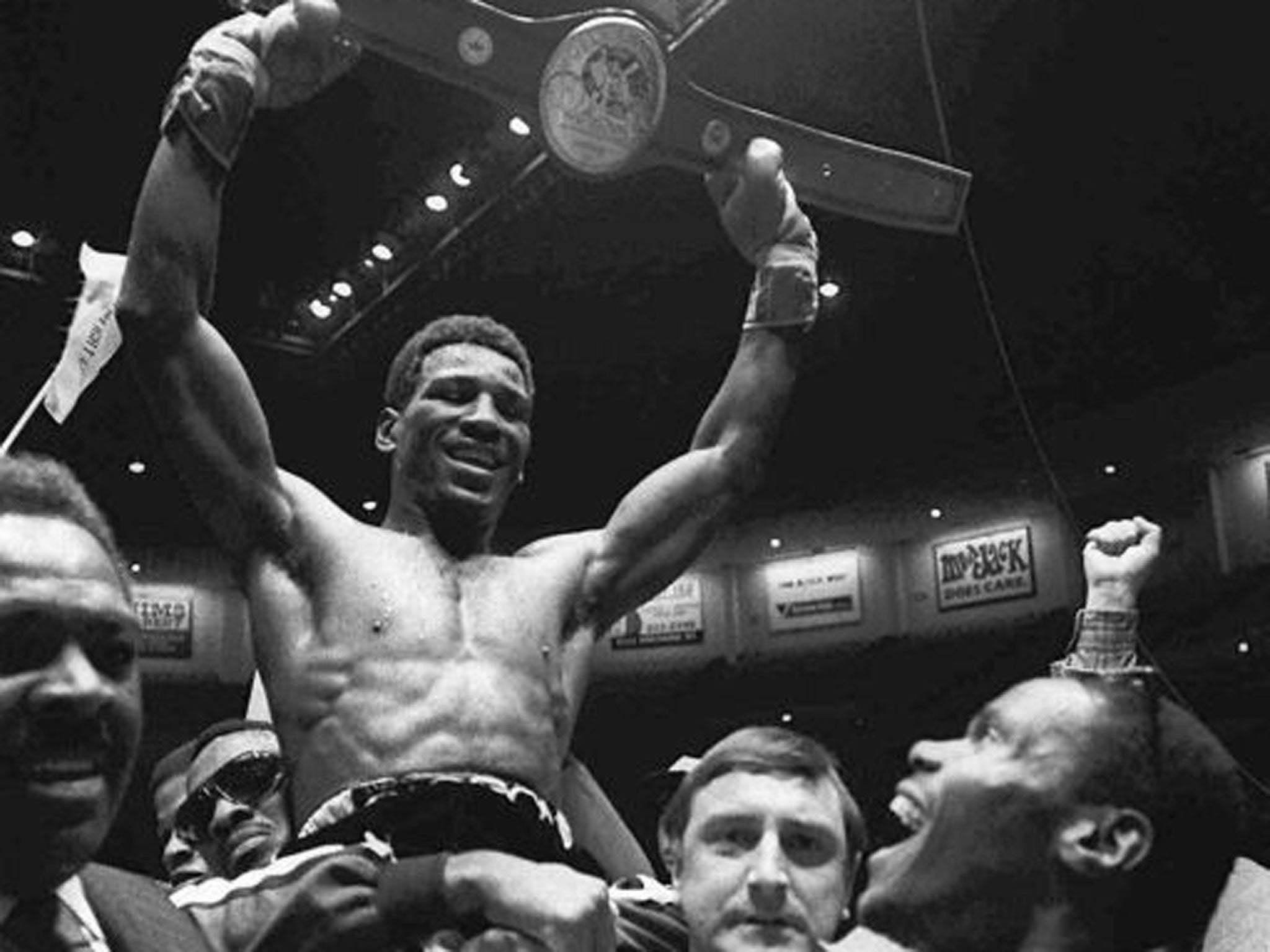

Matthew Saad Muhammad 'Miracle Matthew': Boxer and campaigner for the homeless

Light-heavyweight known as 'Miracle Matthew' thanks to his ability to recover from bloody, heavy beatings

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Nobody saw the small boy leave Maxwell Antonio Roach on the corner, nobody reported him missing and he was just five when he was found walking on the streets of Philadelphia and taken in by nuns.

The nuns gave him a new name and from that point until 1979 he was known as Matthew, after the apostle, and Franklin, after the street he was found on. In 1979, shortly after winning a world title, he converted to Islam and took the name Matthew Saad Muhammad.

Muhammad's mother died when he was an infant and he and his brother were taken in by an aunt. However, the aunt struggled to cope and the elder brother was told to go and lose the five-year-old. He did. "I tried to run and chase him, but he was too fast," said Muhammad.

His life was troubled even after the nuns rescued him; his adoption with a family in south Philadelphia failed to halt the descent and there were too many bloody nights in a street gang and then reform school before he found his way to a boxing gym. "It suddenly all started to make sense," said Muhammad.

In the ring, Muhammad quickly established a reputation for coming back when seriously hurt and this led to his odd boxing sobriquet of "Miracle Matthew". He fought his way as a pretender on the vicious Philly beat to fringe contender, often supplementing his ring earnings with gym wars that enhanced his reputation in a city of brotherly contact.

"My fights reflect my life, the way I had to come back," said Muhammad. "All I ever think of when I'm getting hit is: 'You better win this before the fight is over'." Muhammad, fighting as Franklin, kept winning – and in 1979 he finally got his chance to win the world title against former opponent Marvin Johnson; the pair had shared the ring two years earlier at the Spectrum in Philadelphia, and it had ended in the 12th round with Muhammad the winner. It had been a brutal brawl and the rematch for the WBC light-heavyweight title was even more savage.

Muhammad was cut, bleeding heavily, shaken – but somehow he came back to stop Johnson in the eighth round in a fight that set new levels of pain and resistance. "I can still feel the punches now," said Muhammad.

The first defence was against Liverpool's John Conteh and once again there was blood, guts and shattering knockdowns during an exceptional fight. Muhammad was cut so severely above his left eyebrow in round five that it looked like the fight would be stopped and Conteh crowned champion. However, in Muhammad's corner the veteran cutsman Adolph Ritacco had applied his secret coagulant, which turned out to be roasted tea leaves, to his fighter's brows – and by round nine the bleeding had stopped; a black substance was visible over the wound and George Francis, who was in Conteh's corner, had seen enough. At the end of round nine he rushed over to Ritacco, who threw a punch at the "fucking limey". In round 14, Conteh was dropped twice, but survived until the end of the 15th round, when Muhammad retained his title by a slender margin on points.

Perhaps Muhammad's finest night took place in July 1980, his fourth of eight defences, when he met Mexico's Yaqui Lopez. The eighth round, when Muhammad was hit 71 times without reply, something that no modern referee would ever allow, was ferocious. "I hate to watch my old fights," said Muhammad. "Nobody wants to celebrate that." He was wrong; it was voted the fight of the year and Muhammad came back, took control and stopped Lopez in the 14th round of an unforgettable fight in a forgotten period when too many men made heavy physical sacrifices inside the ring. He was Miracle Matthew.

"You sweat, you work hard, you spill your blood and then they take half of your money," said Muhammad. "I was abused and used by the wrong people – I thought they were my people and I was wrong." It is calculated that he made in excess of $4m during his 68-fight and 18-year career, which finally ended in 1992 with him as a tragic loser travelling to pick up small change for another beating. His riches and his health were long gone before the final round in the ring.

"I know about hurt, I know about pain and I know about surviving," Muhammad used to say whenever he was asked to speak to the homeless in Philadelphia. Muhammad, by the way, was given the Keys to the City of Philadelphia by four different mayors during his career. He needed the keys to a home, though, and in 2010 he sought shelter when he became homeless, staying four months before leaving and working with a homeless organisation. "I still feel some of those punches," he once said. Anybody that has ever watched him live or on TV will know exactly what he means. µ STEVE BUNCE

Matthew Saad Muhammad (Maxwell Antonio Loach), boxer and campaigner for the homeless: born 16 June 1954; died Philadelphia 25 May 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments